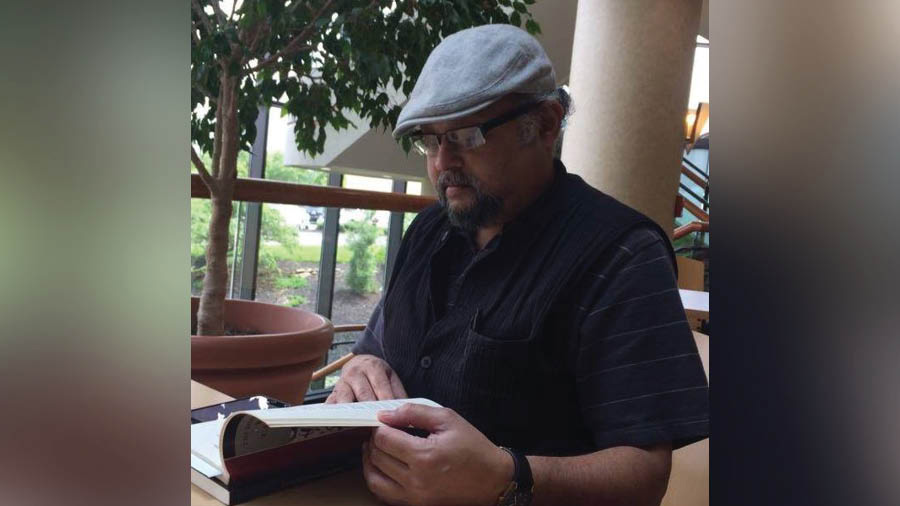

“I’m not interested in the mainstream. Instead, I look for voids or gaps, inspecting ideas that haven’t been explored, subjects that haven’t been covered,” says Nilanjan Mukherjee, 58, based in Cincinnati, Ohio, where he has been for the past 25 years. Mukherjee’s habit of looking where few others do has led him to carve out a twin identity for himself.

By day, Mukherjee is the principal meshing research and development engineer at Siemens Digital Industries Software. His role at Siemens, a company he joined in 1999, revolves around mesh — a system of network topologies that connect nodes and cooperate with one another to transmit information. In early February, Mukherjee was selected to receive the SIAM-IMR Fellow Award for 2023. SIAM stands for the Society of Industrial and Applied Mathematics and is one of the most revered professional societies in the engineering industry.

By evening, Mukherjee, adopting a different first name in Aryanil (the presence of another Bengali poet by his original name made his wife select a pseudonym), is a poet, translator and essayist, who has multiple volumes of verse to his name, both in English and Bengali. Not everyone can understand Mukherjee’s avant-garde poetry. Fewer still can comprehend his work with mesh. In fact, Mukherjee believes there are less than 100 people in the world whose profession requires them to do what he does.

From designing a crane that lasted 25 years to starting Kaurab online

Growing up in Kolkata, Mukherjee’s life was far less esoteric. Born and raised in a family of academicians, Mukherjee took to reading quite naturally and refers to himself as “intellectually self-made”. He changed a number of schools in his formative years before spending six enjoyable years at Jadavpur University, for his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in mechanical engineering. His first job, as design engineer for Tata Motors, took him to Jamshedpur, where he had his first encounter with a group of poets writing for the Bengali magazine Kaurab. Among them was Kamal Chakraborty, Kaurab’s founder editor who eventually handed over the reins of the magazine to Mukherjee in 2004, some six years after Mukherjee had started Kaurab online, the first webzine to be accessible in a South Asian language. While at Tata, Mukherjee also helped build India’s first indigenous crane, which was deployed for more than 25 years and exported to 60 countries. Having completed his PhD in aerospace engineering from IIT Kharagpur, Mukherjee was on the cusp of professional change, which came soon enough.

Mesh that can make anything from golf balls to brassiere

Based in Cincinnati, Mukherjee has been working for Siemens since 1999

“I don’t like travelling much. I’m usually quite content with where I am. At the same time, I’m professionally ambitious,” says Mukherjee, for whom the 1990s entailed going back and forth between the US and India, until, with a son to take care of, he and his wife decided to settle down in Cincinnati. Since then, Mukherjee has worked on a number of mind-bending concepts with his mesh work, often producing results he himself has no idea of. “My job is to write algorithms that generate mesh which goes into software. These software are then sold across the world and you can’t always know who uses them or how,” explains Mukherjee, who was rather amused to find out that some of the mesh developed by him has spawned everything from golf balls to brassieres.

Mukherjee’s hyperspecialised field has also seen him work on Mars rovers and collaborate with a diverse team from across the planet. “A lot of my papers and patents have been shared with Jonathan Makem, an engineering mathematician from Ireland. I’ve worked with talented individuals from Canada, Belgium, France, Serbia, Tunisia….” says Mukherjee.

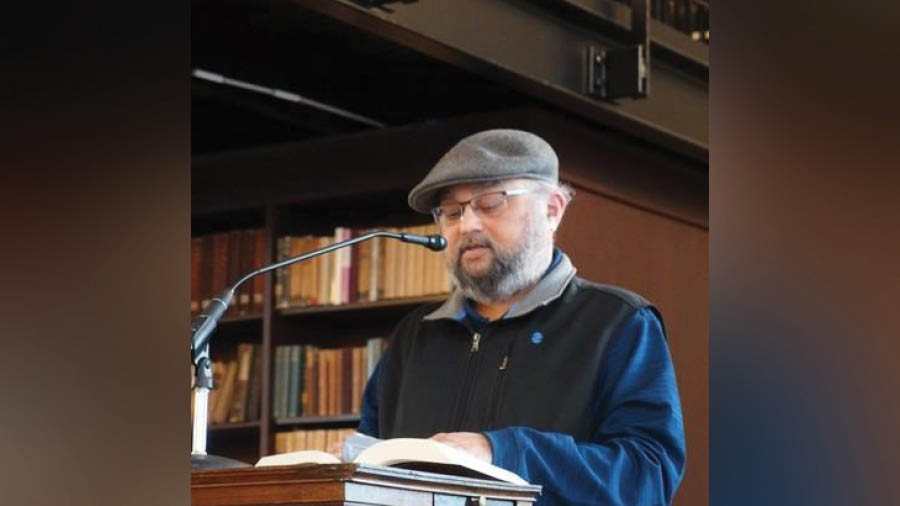

Fresh, firmly both in and out of focus: John Ashbery on Mukherjee’s poetry

The cosmopolitan network is not limited to his scientific career. As a poet, he has hobnobbed with creative minds from different continents and cultures, taking an active interest in translating several poets from English to Bengali, including Peter Gizzi and John Ashbery. Mukherjee highlights the latter “as the only poet to have inspired me. In the US, they say that the first half of the 20th century belonged to TS Eliot and the second to Ashbery. It was an honour to have my first book of English poems, Late Night Correspondence (2007), blurbed by him.”

As part of his commentary on Mukherjee’s poetry, Ashbery had described Mukherjee’s voice as “fresh, firmly both in and out of focus”.

As he speaks, Mukherjee demonstrates a similar quality, an ability to zoom in and out of topics effortlessly. “When I was in my 30s, I found it far easier to switch from my engineering self to my poetic self. My mind was more compartmentalised back then. But as my research work got more intense, the boundaries started blurring. And so I dropped the screen between my morning and evening lives to the extent that I started incorporating concepts from the world of arts into my research papers. This included using the art gallery theorem (formulated in geometry as the minimum number of guards that need to be placed in a simple polygon for all its interior points to be visible) after a visit to a Paris museum and deploying notions of bicameralism (the practice of dividing the legislature into two chambers) and bricolage (as advocated by French anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss) in my research,” says Mukherjee, who is currently planning to combine mesh and poetry for his magnum opus.

‘I could actually look at a fellow human and see only their skeleton’

Mukherjee plans to write a magnum opus that combines his passions for mesh and poetry

“I want to execute a poetic version of a pentimento (a visible trace of an earlier painting beneath layers of a new painting) on mesh. Every digital image we see contains mesh, which on being rendered with colours comes alive in our field of vision. Similarly, every human being contains a skeleton, which on being rendered with flesh and blood comes alive as a person. Just like a pentimento is a painting hiding behind another that sometimes peels through, like the unseen meshes hiding behind every digital image, poetry should also make an attempt to reach the profound truths hiding behind what we perceive as reality,” narrates Mukherjee, before admitting that there was a phase in his life when “I could actually look at a fellow human and see only their skeleton”!

Until Mukherjee’s poetic conception on mesh is born, his bilingual collection called Smritilekha (Code Memory), first published in 2013, remains his finest work, according to him. “It starts with a neurobiologist talking about memory and goes on for 234 pages, partly in Bengali and partly in English. I’ve been told that this may be the longest poem written in modern Bengali,” he smiles. Having published his first Bengali book of poems, Khelar Naam Sabujayan (Greening Game), in 2000, Mukherjee is well-placed to reflect on the evolution of popular poetry, particularly with the rise of Instagram poets on social media: “For many countries and cultures, it’s good to have more mass engagement with poetry, say through poets like Rupi Kaur. They have an important function in expanding and elevating poetry.”

Making ‘Cafe Kinara’ with Aniruddha Roy Chowdhury

Mukherjee (right) enjoying a cuppa with Aniruddha Roy Chowdhury at Roastery in Hindustan Park

When he is not writing algorithms or poems, chances are that Mukherjee is watching an art film. “My initiation into cinema happened through my father at a very early age. Then, while at JU, the film club allowed me to really explore my cinematic tastes. I feel cinema has influenced a lot of my poetry, especially the cinematic techniques of Jean-Luc Godard and this wonderful contemporary Thai filmmaker called Apichatpong Weerasethakul.”

From admiring cinema, Mukherjee should soon be involved in its making. “Talks are going on with my friend Aniruddha Roy Chowdhury to work on a Bengali film called Cafe Kinara, for which I’ll be writing the screenplay. We had originally started collaborating on this in 2014, though it didn’t quite work out back then. But the time has come to revive it,” says Mukherjee. Another connection he has to Bengali cinema is through another of his friends, Atanu Ghosh, whose film Mayurakshi's lead character (played by Prosenjit) is called, well, Aryanil (Roy Chowdhury), with due approval from our man Aryanil Mukherjee!

So, what would he tell the creators and changemakers of tomorrow? “Take the paths less travelled, observe what’s on the margins. Work in areas where not a lot has happened. That’s where you have more of a chance to make an impact, to do what few have done before.”