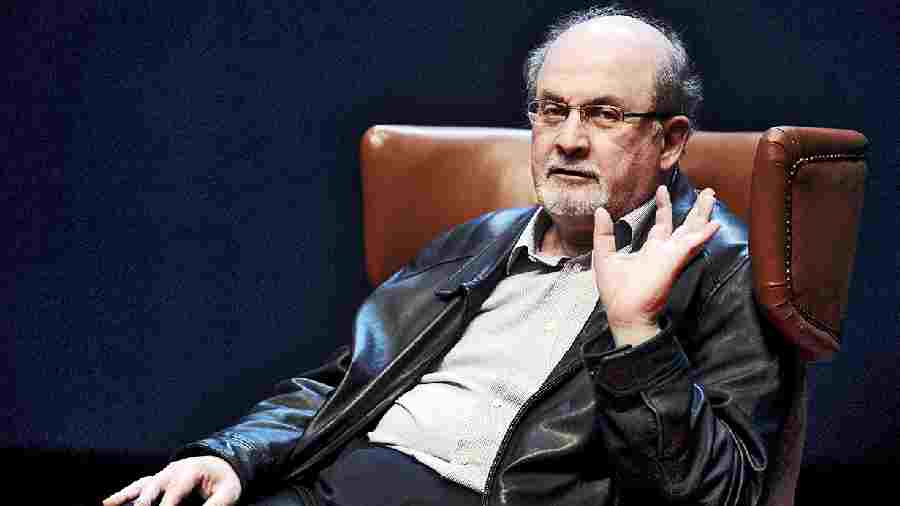

Outside, it was a mild fall day in Ontario, with the leaves turning to crimson and gold. It was September 2002, exactly a year after the world changed with the tumultuous attack on the World Trade Center in New York. Inside the theatre at Ryerson University, at downtown Toronto, it was standing room only. We awaited the arrival of Salman Rushdie, one of this century and the last’s most inventive and brilliant writers. A hush fell over the room. A smiling, slightly portly man with piercing eyes, was ushered on to the stage. And then, with his inimitable charm, as he began to speak about Fury, his book published in 2001 about New York, we were on a magic carpet ride. “Literature is about trying to reach for human truths,” the celebrity author had said that day.

Rushdie has unabashedly maintained that fiction is not merely about documentation, and that stories don’t necessarily have to be only facts. Though research is important too. Writers, he has said time and time again, use mythologies, fables and elements of the fantastic to create worlds, tales, narratives, characters — of the imagination. For instance, by using fairy tales, he maintains, we can get to telling the truth in another way. “It is another door into the truth”.

Perhaps one of the best-kept secrets in the The Satanic Verses publishing story is an anecdote that creates both surprise and admiration for Rushdie as a researcher and writer, who has the inimitable grace and concision to find the truth and then deploy it in the most inventive way. A Mumbai-based magazine that historian and academic Harish Mehta worked for in the 80s had given Rushdie the Gentleman of the Year Award in 1984. The Booker Prize winner for Midnight’s Children in 1981 was the publication’s guest for a week in Mumbai and Delhi, and when he landed at the Mumbai airport one morning on a flight from London, to receive him were Harish (national affairs editor), David Davidar (literary editor), and two other editors. Wearing green dungarees and a jean jacket, Rushdie looked younger than his 37 years. Harish was still a good 10 years younger. At the airport and on the drive to his hotel, Rushdie talked easily about his new book, Shame, heaping sarcasm on the generals that ruled Pakistan.

Harish Mehta remembers the meetings with Rushdie well: “That evening there was a welcome party at a sea-facing apartment on Malabar Hill. After a couple of hours, Rushdie whispered to us (David and me) that he wanted to get out to look at the red-light area. It was for sociological research that he wanted to do for a future book. The producer of Attenborough’s film, Gandhi, Suresh Jindal, also at the party, was to drive us to Foras Road. The entire exercise was essentially academic.

“We slipped out of the party, following Rushdie. Soon we were engulfed by a world of squalor that none of us had seen before or since. Pimps and prostitutes swarming around Jindal’s Ambassador car. Now, we were hustled upstairs to a brothel, and told to sit on cushions on the floor. Glasses of beer were placed before. None of us dared to drink. Who knew what was inside. Rushdie wasn’t drinking in any case. It appeared he was on the wagon. Inside the brothel, Rushdie looked relaxed. Two girls began dancing to some shrill music.

“The pimps looked delighted. But after a few moments, Rushdie, having seen enough, told us that we should leave. He had made enough notes. Perfect. When The Satanic Verses was published in 1988, it became eminently clear how meticulously Rushdie had researched and documented his visit to Foras Road. Much of the ambience and many of the characters in the houses of pleasure found perfect representation in The Satanic Verses.

“Rushdie did not possess any false airs of superstardom. He wore his success as a literary phenomenon lightly. He spoke to us as equals, as young friends, one of us. Well, if you’ve visited a brothel together, even academically, you get initiated into a brotherly rite.”

How surreal, that today, as he lies in hospital, miraculously catapulted to recovery unhooked from the ventilator, and making jokes, the theory of truth-telling through stories which he had spoken to us about, 20 years ago in blustery Toronto, has transformed into praxis. And truth has come at a price. Although oblivious to the indomitable and surreptitious presence of the fatwa — Rushdie has waved it away as no longer a threat in interviews since the late 1990s — 33 years after the fatwa was placed on his head, the demons still pursue him.

Some of us have heard him say, “I am getting on with my life”. Rushdie was always aware that some fundamentalist might try to kill him but that never stopped the writer from creating stories that spoke out. And then suddenly, just bang in the midst of a festival crowd, in a hive of activity in the innocuous western New York county of Chautauqua where 2,500 members of the public were waiting to hear him speak, an innocuous man, sitting in the audience, vaulted on to the stage and stabbed him for 20 long seconds while astonished witnesses were left stunned. Just when hundreds and thousands of readers were almost lulled into believing, just as Rushdie was, that the fatwa had faded into the twilight, the reality of the death sentence seems to have risen from a flicker of dusk. For his unflinching courage and commitment to talking back to masculinist domination and fundamentalism, after 33 years, Rushdie was assaulted brutally, suffered an injured liver and will, in all probability, lose an eye.

Actor Kal Penn (in pic) invoked him as a role model “for an entire generation of artists, especially many of us in the South Asian diaspora toward whom he’s shown incredible warmth”. This is the kind of respect that my Asian students who were second and third generation Indo-Canadians, immigrants like Rushdie, to the US and Canada from embattled homelands like Sri Lanka, had for Rushdie

Hadi Matar — resident of Fairview, New Jersey, of Lebanese descent, sympathiser to the Iranian military — who committed the premeditated, heinous attack on Rushdie, is just the kind of person who was waiting to target this author for his truth-telling. Fellow writers, activists, scholars, cultural producers, a universal fan following of readers, have applauded Rushdie’s abiding advocacy of free speech despite compromising his own safety. Celebrated British novelist and close friend Ian McEwan said Rushdie is “an inspirational defender of persecuted writers and journalists across the world”, and actor Kal Penn invoked him as a role model “for an entire generation of artists, especially many of us in the South Asian diaspora toward whom he’s shown incredible warmth”. This is the kind of respect that my Asian students who were second and third generation Indo-Canadians, immigrants like Rushdie, to the US and Canada from embattled homelands like Sri Lanka, had for Rushdie. In their minds and hearts they were deeply invested in finding modes to create their identity and configure how fascism works to silence voices that are powerful and demand inclusion and equity.

While teaching Postcolonial Literature and Diasporic Literature at the University of Toronto, Rushdie was possibly the most popular novelist in my classroom. One Indo-Canadian student, while discussing Midnight’s Children commented: “The way Rushdie has created a character like Saleem Sinai, by giving him the power to weave in and out of different national, religious and cultural borders, whether it is Hindu, Muslim, India or Pakistan, gives many of us who are hybridised or even mongrelised Asians in North America a new way to configure how we can look at ourselves with a new pair of eyes. And make us feel it’s okay to be this and that.”

Rushdie’s ideas of empowering the migrant, despite living in the hyphen, strikes a deep and abiding chord with many young immigrants from South Asia.

Rushdie’s fourth novel, Shame, an inventive novel on home and belonging, is a favourite text among young Masters scholars, and we can see why Kal Penn pays such a glowing tribute on behalf of not just young, diasporic Asian-North Americans, but all young, mobile global souls who will have more than one home as they traverse the shrinking world.

Shame is a thinly fictionalised, or fantasised, version of Pakistani history. The hanged prime minister, Iskander Harrapa, is based upon University of California-educated Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, hanged in 1978 by his erstwhile friend and successor General Zia ul-Haq (Raza Hyder). The novel’s events loosely parallel those of Pakistani history since 1947.

In Shame, Rushdie says: “When individuals come unstuck from their native land, they are called migrants. When nations do the same thing (Bangladesh), the act is called secession. What is the best thing about migrant peoples and seceded nations? I think it is their hopefulness. Look into their eyes of such folk in old photographs. Hope blazes undimmed through the fading sepia tints. And what’s the worst thing? It is the emptiness of one’s luggage. I’m speaking of invisible suitcases, not the physical, perhaps cardboard variety containing a few meaning-drained mementos: we have come unstuck from more than land. We have floated upwards from history, from memory, from time.”

Among students in the classroom in Kolkata too, Rushdie is a writer whom they find useful to configure ideas of belonging and nation. In my Master’s English literature class, in the Indian Writing in English module, it was revealing to find that Sucharita Chowdhury thought: “The problematic labelling of the author himself with the word ‘migrant’ is worth noting. On the one hand, it signifies the detachment of the author from his mother country and his deep-rooted involvement in the narration of his ‘not quite Pakistan’ on the other. The ‘hopefulness’ here is the hope of finding the real home and true identity, a sense of ‘belongingness’ to one’s own land. ‘Old photographs’ may be interpreted as the only proof for that migrant whose hope to find ‘roots’ is still unresolved. ‘Fading sepia tints’ in the excerpt might be a reference to the faded forgotten past (history).”

In a moving article in The New Yorker, in May 2014, Rushdie remembered the day in 1989 that Ayatollah Khomeini had handed him a Valentine’s Day gift that was both bizarre and life-changing — the fatwa (death sentence, by Ayatollah Khomeini, which encouraged all Muslims to kill Salman Rushdie, the author, and members of his publishing associates of The Satanic Verses). It had been a day full of realism without any magic: He attended his dear friend Bruce Chatwin’s memorial service with Rushdie’s then wife Marianne Wiggins. Chatwin had died of AIDS.

It bothered him that he hadn’t spoken to his son about the fatwa. He talked to his son, holding him close, deciding at that moment that he would tell the boy as much as possible, giving what was happening the most positive colouring he could; that the way to help Zafar deal with the event was to make him feel on the inside of it, to give him a parental version that he could hold on to while he was being bombarded with other versions in the school playground or on television.

“Will I see you tomorrow, Dad?”

He shook his head. “But I’ll call you,” he said. “I’ll call you every evening at seven. “Seven o’clock,” he repeated. “Every night, OK?”

Zafar nodded gravely. “OK., Dad.”

So, does Rushdie regret writing The Satanic Verses? In 2013, at Express Idea Exchange he said: “I would write The Satanic Verses again…. People define their identity not by what they love, but what they hate.” Here is a man who lives the dream of telling the truth with formidable courage. And this is no fairy tale.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Kolkata and teaches Masters English at Loreto College, Kolkata