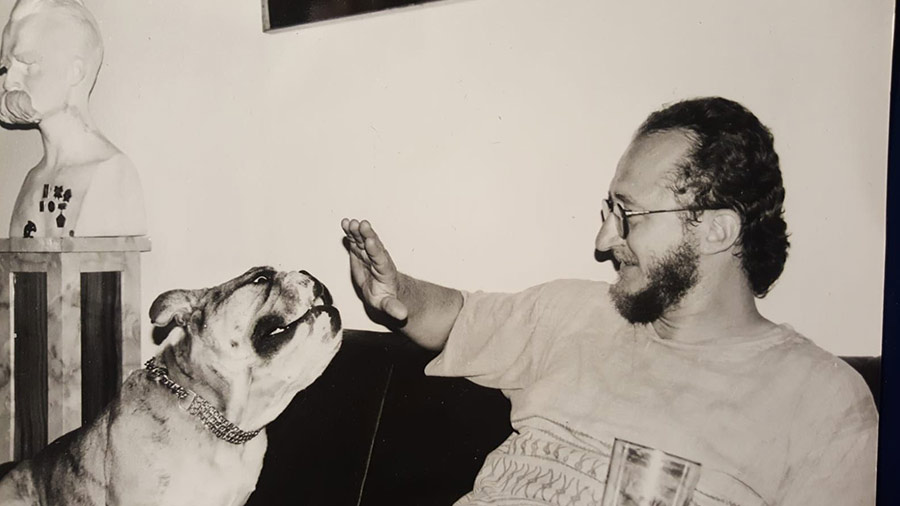

Frank J. Korom isn’t just a professor of religion and anthropology at Boston University. He is an ambassador of cultures and geographies, bringing nuance to belief and rationality to dogma. Having travelled throughout the Indian subcontinent after a teenage fascination with India, Frank sees faith from the lens of both an insider and outsider. My Kolkata caught up with him to know about his adventures, how faith impacts civilisation and more.

What brings you to Kolkata?

I was invited by several universities to give lectures. The first one was at Jadavpur University, where I spoke about how Sufism is entering the West and becoming more democratic. The second lecture was on museum anthropology at Vidyasagar University, Midnapore. The final lecture at Presidency University was about this Tamil-speaking Sufi saint from Sri Lanka called Guru Bawa, who I have been studying. He went to the United States (US) in 1971 and had a major impact there, till his death in 1986.

Tell us about your childhood. How did you gain an interest in India?

Ethnically I’m Hungarian-German and Yugoslavian by birth. My family left for the US when I was four years old. I grew up first in New Jersey, and then in Pennsylvania. As an immigrant child, I never fit in with the rest of the kids and always felt like an outsider. This prompted different interests from other young American boys. While I was not religious myself, my family was Roman Catholic and my maternal grandmother was very religious. She forced my parents to send me to a Roman Catholic school, which I hated. When I got to eighth grade, I convinced my parents to transfer me to the public school system. By then, I was already interested in Eastern thought. One of the first books I read was the Autobiography of a Yogi by Paramhansa Yogananda. It had a huge impact on me, and drew me towards Bengal because he was a Bengali.

‘‘Autobiography of a Yogi’ by Paramhansa Yogananda had a huge impact on me, and drew me towards Bengal’

Since it was the mid-’60s, the ‘guru invasion’ had also begun with the passing of the 1965 Immigration Act, allowing more Asians to come to the US after World War 2. Incidentally, The Beatles also discovered Eastern spirituality around the same time and started using Indian instruments on their records. The music blew me away so much that I went to my local library, found some records by Ravi Shankar and spent a lot of time listening to them. To this day, I love Indian classical music, both Hindustani and Carnatic. In fact, I spent yesterday at a classical music programme in Golpark! I even taught myself how to do yoga from a coffee table book that depicted 108 different asanas. My fascination didn’t stop there and I turned vegetarian for a bit. My parents couldn't understand my fixation and they thought I was insane. I made a vow to myself that one day, I would come to India.

Frank has been a professor of religion and anthropology at Boston University for 25 years Boston University

You started adventuring through India soon after, right?

Yes. I first left home when I was 17. My trip started with Europe because I wanted to discover my roots. I travelled around the continent for six months before going to Yugoslavia, where I spent a month with my relatives. I went on to Istanbul, which was the crossroads for hippie traffic going from Europe to India. At the time, there was this ‘magic bus route’ from London to Kathmandu, which stopped at cities like Istanbul, Tehran, Kabul, Lahore and Delhi. I met people who did it and was fascinated, but couldn’t join since I had no money.

After returning to the US, I worked odd jobs and saved for two years before travelling again. I first went to Germany as an ode to my mother tongue, and stayed with a guy I met on the Orient Express! I also did a short stint of agricultural labour in Greece, before hitchhiking to Istanbul. This time, I didn’t stop there. After crossing over to Iran, I travelled through Afghanistan, Pakistan and finally to India.

In India, I travelled the length of the country, from Goa to Bombay, Kerala to Rishikesh, before spending my 19th birthday in Kathmandu. I had started running out of money by then, and crossed over to Pakistan, where I waited for a month for the Afghanistan border to open. When I finally got a two-week transit visa, I went to Kandahar, then to Iran, and traced back my journey. When I finally returned to America, I had been away for 18 months with a budget of just $2000. It wasn’t always easy and I often stayed in run-down motels for Re 1 a night and even camped with a backpack and sleeping bag at times. To be fair, though, I have retained one thing from my travels. Even though I have an American passport, I feel like a global citizen, who is just as happy in Germany as in Kolkata.

Frank feels passionately about the diversity of religion across geography, and believes that each religion should be seen within its own context rather than through a Western lens Soumyajit Dey

How did you go from being an explorer of culture, to a scholar in it?

When I got back to the US, I didn’t know what to do with my life. Back then, Americans were very insular and only thought about the world that was within 30 metres of them. But, people found my travel stories interesting.

I worked odd jobs for a while and started taking evening courses in culture. Eventually, I moved from the East Coast to Colorado to study a bachelors degree in religious studies and anthropology, with a focus on South Asia. While doing a course at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, I met my then-wife, who was a master’s student. However, I soon had to leave for Benaras, where I got a grant to study Hindi and Urdu at the Banaras Hindu University. My thesis was on the Panchkoshi Yatra, a barefoot parikrama of the entire city over five days. After finishing my degree, I received another grant to come back to South Asia, and spent a year studying Urdu in Lahore. While I was there, my partner, who was a Bengali, lived with her uncle in Delhi. Indira Gandhi got assassinated that year, so they closed the border and I was very nervous about getting a visa. We finally had our wedding in Delhi, and after spending some more time in Lahore, we finally came back to the US together!

After our marriage, my language of focus changed to Bangla and I fell in love with it, since my mother-in-law would recite beautiful Bengali poetry. I even came to Bengal for my doctorate research, while doing my specialisation in South Asia from the University of Pennsylvania. My focus was Dharmaraj Puja, a three-day village ritual in rural Bengal, based on a deity who is considered the creator of the Bengali pantheon of gods.

What were some myths about India that were debunked during your travels?

When I first found interest in Indian religion, I had this romantic idea that everybody in India was doing yoga and meditating all the time! I crossed the border from Pakistan to Punjab and found myself in the midst of hustle-and-bustle in Amritsar. I then went to the Golden Temple, and it had that beautiful silence I was looking for. So India had both spirituality and a thriving metropolis. It was in the process of becoming a functioning post-colonial society, and people were just trying to survive like everywhere else in the world. On top of this, many of the sadhus I met weren’t real either! (chuckles)

‘The Golden Temple had that beautiful silence I was looking for’ TT archives

How do you break down something as complex as religion to students?

I took my interest in religion and started turning more towards anthropology. My questions were around the cultural determinants of a religion and what makes a person desire it.

So, I approach religion through culture. According to Marxist philosophy, the function of religion is to alleviate the pain and suffering of an average worker. Religion manifests itself not in thought, but action. That is why I study ritual because it is the manifestation of these abstract ideas and concepts and can be documented by filming and recording. I don't look at religion as an abstraction, but a part of everyday life. I have four main areas of teaching: expressive traditions, contemporary religion, diaspora studies and transnationalism.

Of these, expressive tradition refers to the performative dimension of culture, i.e. things that we do which we don't have to. It comprises everything external to the spiritual part. For instance, when stories from the Ramayana are performed as a song-and-dance routine, a culture is expressed through an artistic and aesthetic lens. That is a ritual.

'Contemporary religion is the study of modern religion i.e., how people live religion every day. Under diaspora culture, I explore the various diasporas within Indian culture'

Contemporary religion is the study of modern religion i.e., how people live religion every day. Under diaspora culture, I explore the various diasporas within Indian culture. To trace back civilisation, kingdoms like the Cholas first expanded to South East Asia. Then, during the British empire, communities like Sindhis and Gujaratis were seafarers and went to Africa for trade. During this time, India began exporting people to places like Trinidad, Jamaica, Fiji, Mauritius, Madagascar and East Africa. These places had plantation economies and were a part of the British Crown, so a lot of people from rural Bihar signed contracts without complete knowledge, and were shipped off to far off places for five years. After the completion of their tenure, they were supposed to have the money to return to India, but ended up staying there. If you go to present day Trinidad, about 50% of the population is Indian.

The diaspora have their own versions of a religion too, with Muharram being not just an Islamic event in Trinidad, but an important symbol across religions of Indian identity on the plantations. Another diaspora emerged during the 1960s because of ‘brain drain’, where middle-class Indians started sending their eldest sons to study in the UK and US. They became NRIs with well-paying jobs, and initially worked there to pay-off family debt, but often ended up staying back. But today, everything is transnational or global because of smartphones and social media. You don’t have to go to the countries you are studying because of the internet. Transnationalism looks at how ideas and material goods flow back and forth across cultures. It can prominently be seen in the globalisation debate, which started with decolonisation. A major example of this is how India kicked out Coca-Cola in the 1970s to manufacture swadeshi goods, and this brought the advent of Thums Up.

You mentioned that the same religion evolves with geography. Can you tell us how?

Look at how Indian culture spread during the Chola dynasty to Bali. People in Indonesia still practise Hinduism, but it won’t be recognisable to most Indians because it has evolved into something very different. There is a Thai version of the Ramayana and a Jain version of the Mahabharata, both of which have alternations from the mainstream versions.

Even the way I teach Hinduism can lose some students because Indo-Americans consider Hinduism to be this universal phenomenon that their grandparents carried from India when they left the country. When they travel to India, moving in air-conditioned cars between privileged relatives’ houses won’t show them the real India. Hence, I always try to make a distinction between classical Puranic Hinduism and vernacular local and folk traditions. Every language in India has a Ramayana! The Bengali Mahabharata even has elements of Islam, with a story about the Prophet’s grandsons. Bangladesh has a jatra about it during Muharram. Within the country, too, the Hinduism of south India is completely different from that of north India. If you go to Sri Lanka, the Hinduism of Jaffna Tamils is different from the Hinduism in Tamil Nadu.

Similarly, vernacular traditions of bolis and dialects also create diversity.

‘The Bengali Mahabharata even has elements of Islam, with a story about the Prophet’s grandsons’

What unites and what divides us then?

This is one of the central questions when I teach anthropology of religion. There's probably not a culture in the world that doesn't have something resembling what we call ‘religion’. On the other hand, the world is a very diverse place, there are naturally differences. The debate is between universalism and cultural relativism. The universalists say that it's all the same, while cultural relativists say that each culture is different and you have to understand them on their own terms. The taboo in anthropology is reductionism, when you strip down a particular cultural phenomenon to the bare bones to compare it with something else.

I always emphasise that Hinduism’s diversity is its strength, so you can’t see it through the same model of the West. Dharma literally means duty, but it is referred to as the alternative for religion. Even though Arabic has no equivalent for religion, Din is used as reference, but has a different connotation. Mazhab in Urdu refers more to the literary dimension of teachings, but is interchangeably used with religion. Making this deconstruction is important. You have to understand any religion on its own terms and we must free our minds from these cages. Unfortunately, a lot of Americans are learning Hinduism as a 19th century reformed version that came into existence after the Bengal Renaissance, with the Brahmo and Arya Samaj, and the Ramakrishna Mission. They all preach a kind of universalism, but there is no one way of thinking in Hinduism.

‘I always emphasise that Hinduism’s diversity is its strength, so you can’t see it through the same model of the West. ‘Dharma’ literally means duty, but it is referred to as the alternative for religion’ Shutterstock

How do you explain these contrasting versions of a religion to students, given the sensitive lens many hold?

Although religion is a very important phenomenon, most young people are not interested in it, even if their behaviour might be impacted by it. I try to be as respectful as I can without sugarcoating it. I tell people that if they are in my class to hear all the good things about religion, they are maybe in the wrong class. I teach religion from a critical, analytical perspective. You can't look at any phenomenon without looking at both sides of the coin. The Crusades is an example where many people died in a holy war between Muslims and Christians and both sides committed atrocities. Even in Hinduism, you can't talk about the Mahabharata and yoga, while ignoring the caste system. American Indians often don’t want to discuss caste because they feel “it is something of the past” to which I always ask them who cleans their toilets in India. If a whole generation is ignoring caste, it will never be dealt with.

My approach is to sensitise students by beginning with local and moving onto global. If I am teaching conversion, which is a universal phenomenon, I would start with conversion among a specific community during a specific time. Interestingly, Hinduism never had conversion before the 19th century, and it was Dayanand Saraswati who borrowed the concept from Christianity because he was worried that Hindus would become a minority in India. This fear of numbers is universal and the same discourse in America is about race, not religion. Either way, it is discrimination built on people’s fear. Contextually, time and space are important to understanding anything.

It also has to go beyond just discourse. I have had angry phone calls from parents when I talk about the Babri Masjid demolition, and they ask me not to include politics in religion. My point is, no religion is inextricable from the world around it. I have been engaging with this struggle for more than 25 years at Boston University, and still haven't mastered the art of presenting it in a way where everyone is happy.