This is for those who still refuse to believe. That the gods too can be guilty of bias.

Unabashedly biased. So enamoured they were of the land of Victor Trumper, the romantic; the red-hot Ray Lindwall, or Keith Miller, explosive and flamboyant, that they decided to bestow upon their country another heroic figure. As if some master creator had chosen to breathe into his art all of life’s unrealised perfections.

But wait! What did the gods do?

Nothing much. They made Dennis Keith Lillee an Australian.

And omnipotent as the gods are, they even conjured up the perfect plot to humiliate the rest.

Gavaskar, Kanhai, Sobers, Lloyd...

Consider this: which team, even the lowliest in cricket’s hierarchy, would want to be dismissed for 59? And that was a Rest of the World XI, a lineup that dazzled with stars, among them Garfield Sobers, Rohan Kanhai, Clive Lloyd and Sunil Gavaskar. What godly conceit!

The Rest of the World XI had a lineup that dazzled with stars, among them (clockwise from top left) Rohan Kanhai, Sunil Gavaskar, Garfield Sobers and Clive Lloyd Getty Images

As if that weren’t enough, the gods did it through one man. Lillee, of course. Who else?

“I think that was the most memorable match I’ve played in from a personal performance point of view…,” Wisden would quote Lillee as saying.

Lillee’s bowling figures that unforgettable December morning read: 8 for 29 — one of cricket’s most terrifying spells of fast bowling ever.

That was many years ago. This Saturday is the 50th anniversary of that date, December 11, 1971. One of the unwritten codes for those who come later is that they must commemorate things past.

Remembrance serves another purpose too. It helps us relive moments of glory and, in that momentary retrieval, takes us back in time to the timelessness of memory. Lillee’s spell that day, on Perth’s lightning-fast pitch, was timeless.

Rhythm Divine

But we’ll return to that later. First, a quick recap. It was the second of five ‘Tests’ between an Australian XI and a World XI side. The series, put in place after an aborted one against South Africa, did not get Test status, but with Sobers leading the world team, a contest was very much on.

The Rest of the World team, captained by Gary Sobers, that toured Australia in 1971-72

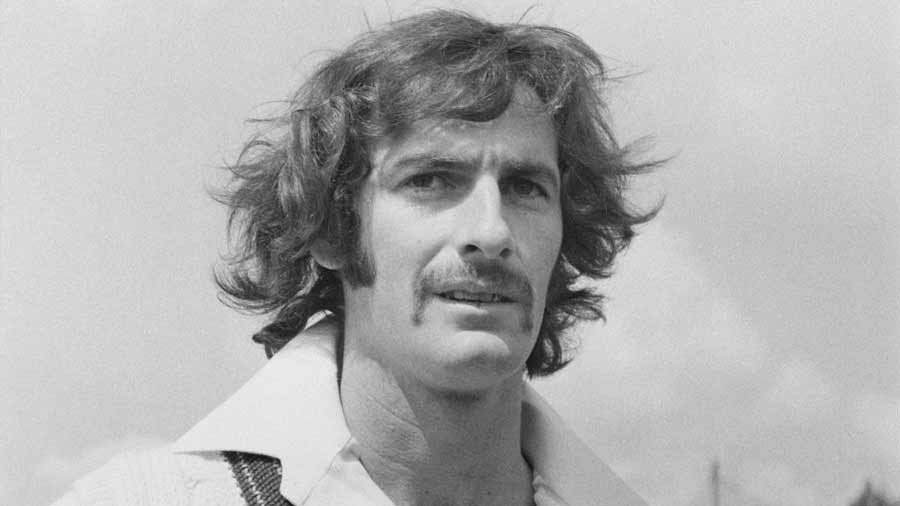

Lillee, 6ft-tall, young, ruggedly handsome, flowing mane flying in the breeze, long athletic legs loping towards the crease, exemplified that intent. Seldom had rhythm looked so menacingly perfect.

Realise now, how incorrigibly partial the gods were?

Hear it from Ian Chappell. “It was a terrific series… some good things came out of it for Australia,” Chappell, captain of that Australian side, says in a video available on YouTube. “Well… three players really came of age, in (Rodney) Marsh, Greg (Chappell) and Dennis Lillee… But the big thing, probably the most important thing for the team, I think, was Dennis Lillee.”

It was, most certainly so, that day at the WACA, the Western Australian Cricket Association ground.

Earlier in the morning, Lillee had got Sunil Gavaskar with a vicious lifter before the star of India’s 1971 Caribbean sojourn had managed a run on the board. Farokh Engineer, who had opened with Gavaskar, was his next.

Keeper Stood 25 Yards Back

But Lillee now felt exhausted and wanted rest. “Some sort of virus was going around Perth at the time — and, after bowling a couple of overs for the wickets of Gavaskar and Engineer, I felt terribly tired and asked Ian Chappell if I could possibly have a rest. He talked me into having one more over and things suddenly began to happen after (Graham) McKenzie dismissed Kanhai and Zaheer (Abbas) was run out.”

From then on, it was Lillee all the way.

Tony Greig became Lillee’s third victim, undone by a reckless slash that probably didn’t get time enough to adjust to the searing pace. Lillee, 22, was then tearaway quick.

The scoreboard read: 46 for 5.

Lillee: 3 for 29

If cricket is a metaphor of the immutable ebb and flow of the universe, fast bowling would be the perilous uncertainties of life. But danger can be fascinating — and Lillee was its triumphant embodiment.

Coming back to the game, Sobers walked in next. Over to him. “I remember walking out to bat and I looked back and I (saw) Rodney Marsh was standing about… 25 yards back,” Sobers would recall years later.

“What are you all doing back here?” he asked.

“You’ll find out,” Marsh had replied.

He did, ‘gloving’ one a few balls later, as Marsh grabbed the early offering with minimum fuss.

Sobers c R.W. Marsh † b D.K. Lillee 0

World XI: 46 for 6

Lillee: 4 for 29

Lillee was rather modest when he recalled that moment on the YouTube video. “Well, anyone, who was going to confront the greatest cricketer, I have ever seen, you know, obviously it’s one of apprehension,” he would say.

The Making of Dennis the Menace

Dennis Lillee’s statue outside the Melbourne Cricket Ground Michael Dodge/Getty Images

That day, though, only one side must have felt a sense of foreboding. And certainly not the one Lillee was playing for.

The remaining four wickets would also fall to Lillee — Richard Hutton, Intikhab Alam, Bob Cunis and last-man out Lloyd completing the dismal parade back to the pavilion. Since dismissing Greig, Lillee had effectively picked up five wickets for nothing. Needless to say, the world team, 290 runs adrift in the first innings, lost the match by an innings. But that was not unexpected and, in the lengthening annals of the game, just another necessary statistic. More important was how the plot unravelled and its psychological impact on a young fast bowler, now ready to scorch the world.

“I was comfortable that I was part of the team once I got that eight-for…,” Lillee says in the video, adding that more than the eight-for, “I now felt that I was contributing to the team… I think that was terrific for me, mentally.”

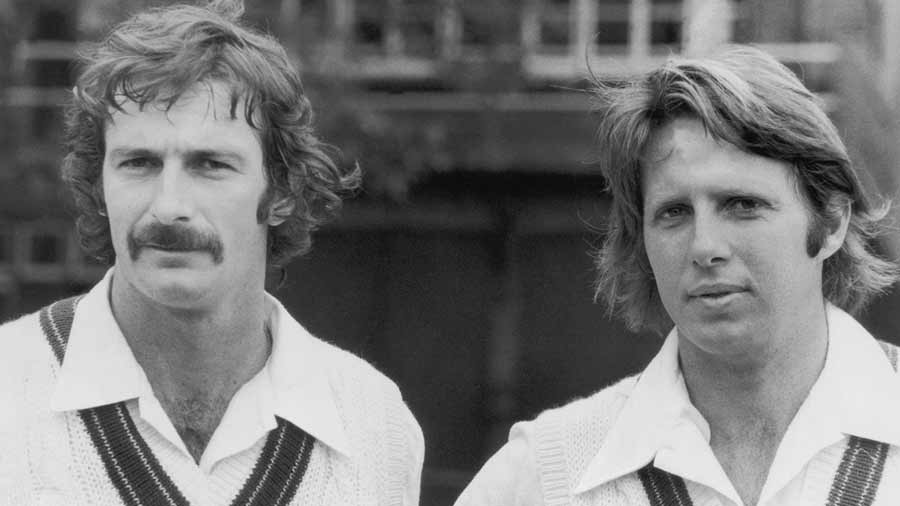

Over the next decade or so Lillee would go on to terrorise batters, often with partner-in-intimidation Jeff Thomson. The two were probably the reason for what might well define two eras in the sport: before helmet and after.

Lillee with partner-in-intimidation, Jeff Thomson cricket.com.au

In between, Lillee would reinvent himself, relying more on variations and movement but losing none of his destructive edge, after spinal stress fractures had threatened an untimely end to his career.

By the time he called it a day, he had broken Lance Gibbs’s then world record of 309 Test wickets to finish with 355 from just 70 matches, one of the few instances when greatness deigned to concur with numbers.

Is Lillee the greatest fast bowler of them all? Why bother? Let’s just say, in the land of The Don, it was a Dennis who made menace look beautiful.