The most under-celebrated heritage address in Calcutta is in a sub-sub lane of central Kolkata. This is the simplest navigation: if you are walking northwards along Chittaranjan Avenue, turn right into Eden Hospital Road. Keep straight beyond the Nirmal Chunder Street intersection and enter Premchand Boral Street.

Sepia has brush-stroked this street. One cannot see fresh paint for metres. You can cut ‘has been’ out of the air. Among the early structures on the right housed the musician Raichand Boral. Cross his home and take the first right. A short distance down take another right. A few buildings down on the left is a structure you would not give a second glance.

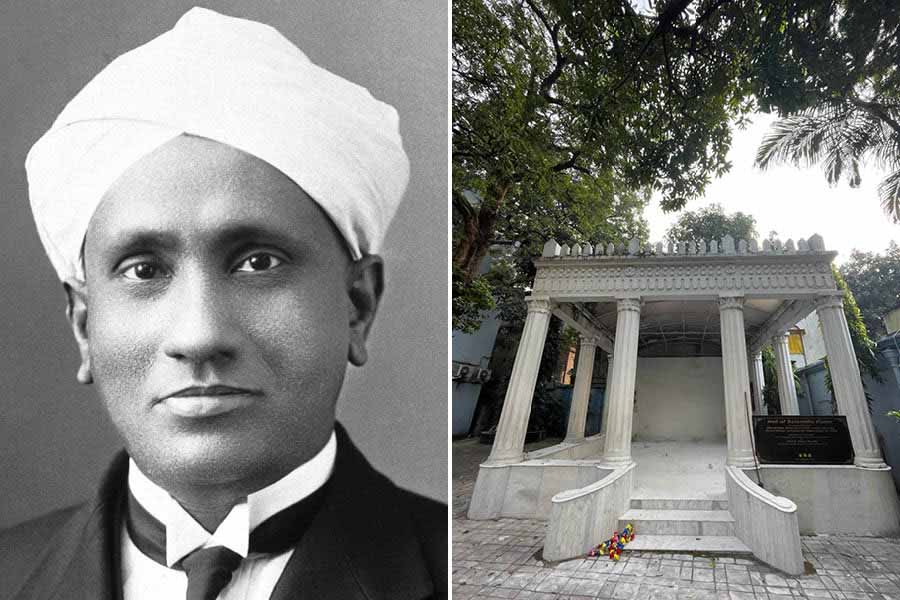

My guide nudged me inside. “Aashun,” he said. He then pointed to a home on the second floor. “Dekhte parchen?” he asked. In that house lived the man who expounded that light scatters and changes wavelengths when passing through transparent material; having proved this, he turned to light diffraction by acoustic waves (acousto optic effect) and the spectroscopic behaviour of crystals.

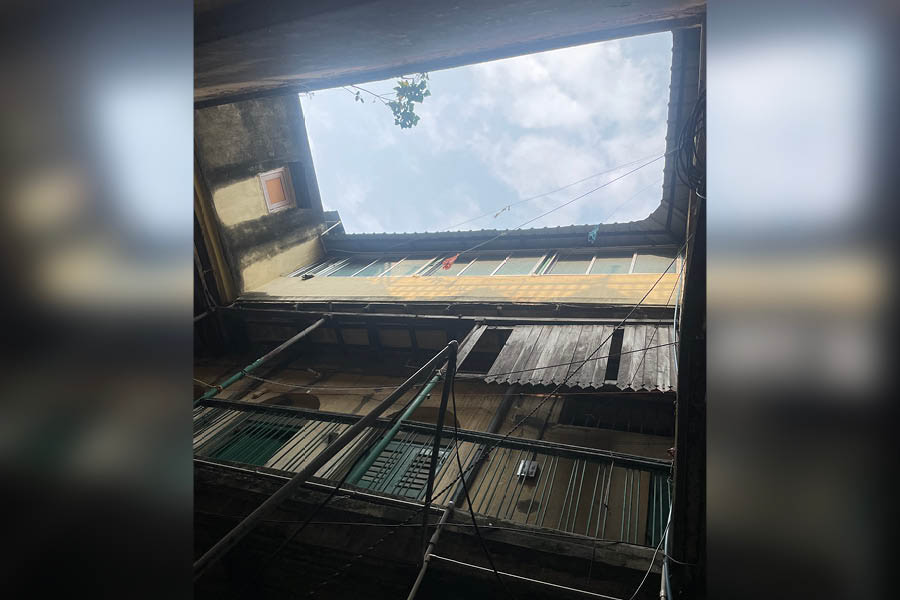

The house and its entrance

And just as it happens, all this would have been largely remained school rote material forgotten by millions, but for the fact that this person who stayed in this modest dwelling – now appearing even more modest down the ages – became the first Asian to win a Nobel Prize for science and the first Indian to be presented the Bharat Ratna.

I fantasised: a focused scientist rising before dawn, leaving for the Science Association a 5.30am, returning at 9.45 to scoop bath mug-fuls out of stored receptacles, chanting the morning hymn in a room corner, applying white paste on his forehead, sitting for a modest floor breakfast prepared by his wife, slipping his head into a pre-knotted tie, placing the turban on his head with two hands firmly holding its sides and stepping out at 10.30. Religiously.

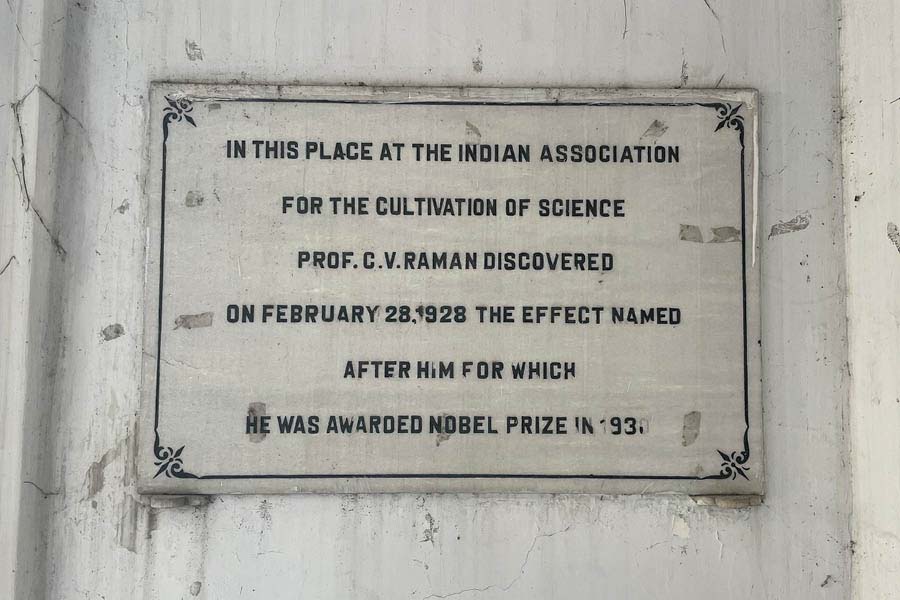

CV Raman came to Calcutta in 1907. He was appointed as the Assistant Accountant General of the finance department for Rs 400 a month (including Rs 150 because he was married). Each morning, Raman would step out of Scott Lane (where he lived at that time) and climb into an electrical tram that passed Bow Bazar Street on his way to the Dalhousie office. While at a window seat, he noticed a board that said, ‘Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science’. On the return journey, he stepped off the tram and headed to this location at 210 Bowbazar Street. Raman discovered that the institution, inspired by the British Association and the Royal Institute of London, had been established in 1876. India’s first science institute had been created to undertake original research. He presented his research credentials; he was just the person the Association had been waiting for. His day job sustained the family; his evening engagement sustained him.

Inside the house

Raman was a solitary man with a singular aim. He created a mini-laboratory at home so that his experiments would not need to be interrupted by closing time; he moved into the Premchand Boral neighbourhood, prompted by the fact that he could construct a pass-through between his residence and the Association that saved him a few minutes a day; he wrote 27 research papers in his first decade in Calcutta even as he kept a day job; he researched the phenomenon of light and then turned to the acoustics study of the veena, violin, tabla and the mridangam.

When Sir Asutosh Mukherjee (in his capacity as the vice-chancellor of Calcutta University) mobilised funding for a science university, he approached Raman with a job offer. This was a contrarian decision on two counts: Raman was formally under-qualified for the post and would have to technically head others with superior credentials. Besides, a fledgling university was competing with the might of the Empire in retaining talent.

I can visualise a conversation between the young Raman and his immediate senior.

‘You are being reckless, Raman.’

‘Sir, this is what I wish to do in life.’

‘Balance your job and your interest, Raman.’

‘Science requires singular attention.’

‘How can you even think of leaving a settled government job and moving to an untried university.’

‘I would be able to displace the status quo more effectively in the university.’

‘You would be endangering the interests of your family, Raman, by taking a Rs 500 reduction in monthly remuneration.’

‘Sir, my wife and I have few wants and no children. I can’t see us spending more than Rs 200 each month.’

‘Do you realise you could soon be included in the Viceroy Council.’

‘Can I ask for a few days of official leave to check the suitability of that new job?’

‘Much as I would like to help you, Raman, the official rules will not permit it.’

‘Then regretfully sir, I must resign.’

Raman was appointed lecturer at 29 on the basis of no degree and no previous teaching experience; only his reputation preceded him.

I will not go into the scientific minutiae of what he achieved; this would be best addressed by the competent. What I will celebrate are the various things he was that we are not: Raman was more interested in the examination of Indian stringed instruments than in playing them, concluding that the value of repetitive vibration was influenced by the string thickness and length; he deployed a carbon arch lamp, mirror, tuning fork and photo plates to film the strings while they were being vibrated. He constructed a mechanical violin from laboratory waste, keeping the bow in a firm position while the violin was continuously moved so that he could research more sound wave variables. He concluded that Indian musical instruments were more melodious than western equivalents because the drum sheet was thicker in the middle and thinner at the edge. Or when returning by ship from London, he noticed the deep blue waters of the Mediterranean and using a nickel prism, binoculars, magnetic analyser and a scattering net, he wrote sheets on the phenomenon that the bluishness was due to the water and not light reflection from the sky.

Raman concluded that Indian musical instruments were more melodious than western equivalents because the drum sheet was thicker in the middle and thinner at the edge Shutterstock

One can visualise Raman: picking up simple objects that people like us would use as paper weights, turning them over, studying them, holding them to the sky to examine filtered sunlight quality, knocking on them to hear resonations. We see objects; Raman ‘saw’ the natural principles that went into them. We play musical instruments; Raman examined why a tune extracted from a violin floated longer than a tabla percussion. He analysed the physics behind the reality of things; he provoked himself with wider realities than most.

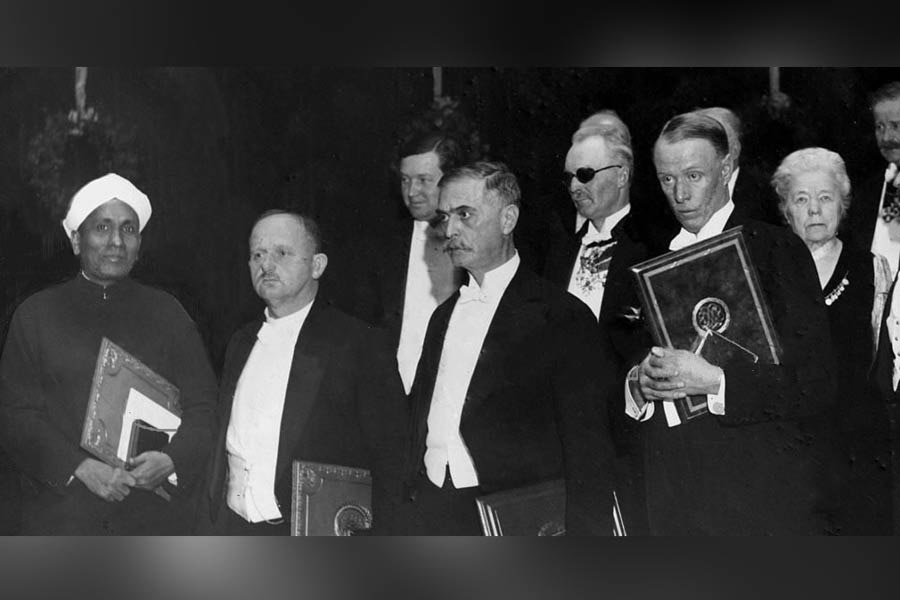

This explains his obsessions. Between 1910 and 1920, Raman focused on acoustics; across the next decade he turned to visual perception and light scattering; from 1930 to 1940, he was attracted by light diffraction by acoustic waves, ultrasonic and hypersonic frequencies and Raman reflection from crystals. During the decade leading to 1950, Raman researched the behaviour of diamonds and crystals; from 1960 to 1970, he focused on pigments and the perception of colours. One presumes that his most frequently used word was ‘Why’. Raman was knighted in 1930 and awarded the Nobel at 42 (the only Indian to have been awarded the latter for original experimental work within India).

Raman at the 1930 Nobel Prize Award Ceremony Wikimedia Commons

When he was unwell in his last days, he regretted the selection of the first hospital floor as that prevented him from seeing the flowers and at the gardens below (the bed height was raised to counter this shortcoming). When he died in 1970, he donated his property to the institute he once headed, was buried within the premises, religious rites were replaced with a sapling and there was no granite memorial in his name.

The man enhanced respect for Calcutta; the city did not repay its gratitude. Even though he spent the most celebrated years of his life in a Central Calcutta bylane, there is no major road named after CV Raman in the city; most neighbours will not know where he lived

I turn to a favourite Raman quote: ‘I want to say to the young men and women sitting before me that they must never give up hope and courage. You can get success only when you do work with courage, enterprise and devotion. I can say this firmly that the Indian mind is second to none other’s mind, but maybe we lack motivation, a spirit which gives us resolve to work. In my view, we are victims of inferiority complex. There is a need to decimate the feeling of inferiority prevailing in the country. We will have to awake our encouragement and motivation, so that we can get back our mark of real identity.’

I end with an irony. The man enhanced respect for Calcutta; the city did not repay its gratitude. Even though he spent the most celebrated years of his life in a Central Calcutta bylane, there is no major road named after CV Raman in the city; most neighbours will not know where he lived; the office where he worked does not know the room in which he sat; the building where he stayed does not have a memorial plaque; there is no prominent statue of him anywhere in the city. Christ said: ‘A prophet is not without honour save in his own country, his own relatives and in his own house.’

If Raman had been born in Calcutta, we might have considered him as one of our own.