Every young nation needs its foundational heroes. For a newly independent India, Homi J. Bhabha was one such hero. Hailed by generations as the “Father of the Indian nuclear programme”, Bhabha was not just India’s most prominent astrophysicist and the brains behind institutions like the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) and the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (previously founded as the Atomic Energy Establishment, Trombay). He was also one of India’s last polymaths who dabbled in the sciences and the arts with equal authority and shone as a diplomat of considerable prowess.

Bhabha’s story has recently become a talking point thanks to the OTT series Rocket Boys (on SonyLiv). But for Biman Nath, an astrophysicist at Bengaluru’s Raman Research Institute and the author of Homi J. Bhabha: A Renaissance Man Among Scientists, (published by Niyogi Books), the show only offers a calibrated caricature of Bhabha, both as a professional and as a person.

Biman Nath’s book provides valuable insights into Bhabha’s professional and personal life as well as the story of India’s nuclear journey

My Kolkata caught up with Nath, whose interests span from gases to galaxies, to take a deep dive into who Bhabha really was, how he changed science in India, his relationship with the likes of Vikram Sarabhai and Meghnad Saha, and more.

Edited excerpts from the conversation follow.

Bhabha was an institution builder who could build and motivate a team

Nath is an astrophysicist at the Raman Research Institute in Bengaluru Courtesy: Biman Nath

My Kolkata: The subtitle of your book calls Bhabha a Renaissance man? Does it simply reflect his aptitude and competence in both science and art or is there a deeper temperamental inclination you wanted to capture?

Biman Nath: Yes, Bhabha’s interest and ability in science and art was a factor in me using the term Renaissance man. Bhabha was a first-rate theoretical physicist who was instrumental in making possible the nuclear energy programme in India, but apart from that, he was also an institution builder who could build a team and motivate them, organise and get things done, which is a completely different ball game. He was adept in both the technical aspect as well as the logistical aspect of whatever he undertook. That’s another reason I’ve used the term Renaissance man.

How important were Bhabha’s family connections in charting out his professional success? Had he not been from a wealthy and eminent family, would he have been able to make it as big as quickly as he did?

His family connections were certainly very important, especially in getting the funding for TIFR. But even the fact that he went to Cambridge University, where the Cavendish Laboratory was creating history at the time, and was exposed to a certain intellectual environment was, in part, a product of being at the right place at the right time. Having said that, Bhabha also knew how to use his network and cultivate connections so that they helped him later on in his life.

The funding for TIFR became possible, in part, due to Bhabha’s extensive family connections TATA

Bhabha didn’t suffer from self-doubt at any point

Did being a part of the Parsi community, who were quite close to the British without being subservient to them, also give Bhabha a distinctive edge?

Yes, I guess it did. It gave him an additional self-confidence, because he definitely didn’t suffer from any mental obstacles such as self-doubt at any point. The ease with which Bhabha mingled with both the Europeans and the Indian nationalists gave him a wider perspective on a number of things and, of course, a wider network to tap into.

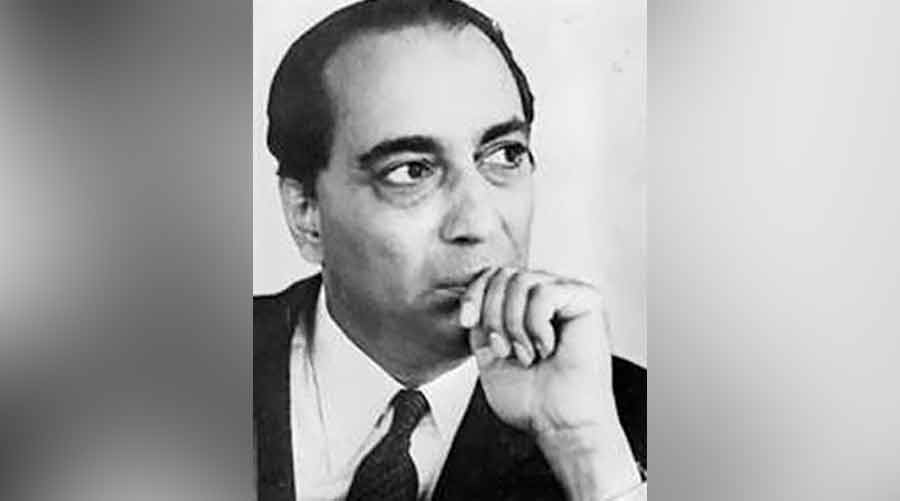

His ‘brain was extraordinarily active’ as a child

As a child, Bhabha had trouble sleeping and was interested in a wide range of activities Wikipedia Commons

In your book, you mention that Bhabha struggled to sleep as a child because his “brain was extraordinarily active”. Could you characterise what thoughts and passions would keep the young Bhabha awake?

The phrase that his “brain was extraordinarily active” came from a French doctor who wanted to assure his parents that there was nothing wrong with Bhabha not sleeping enough as a child. What was his brain active in? Well, he was an active reader as an adolescent, everything from poetry to science. In school, he started reading pretty advanced textbooks, which eventually led him to read about relativity. He also loved playing with toy models and all sorts of wheels, gears and cranes. Plus, he was trained to play the violin.

He believed in using science for the betterment of the human condition

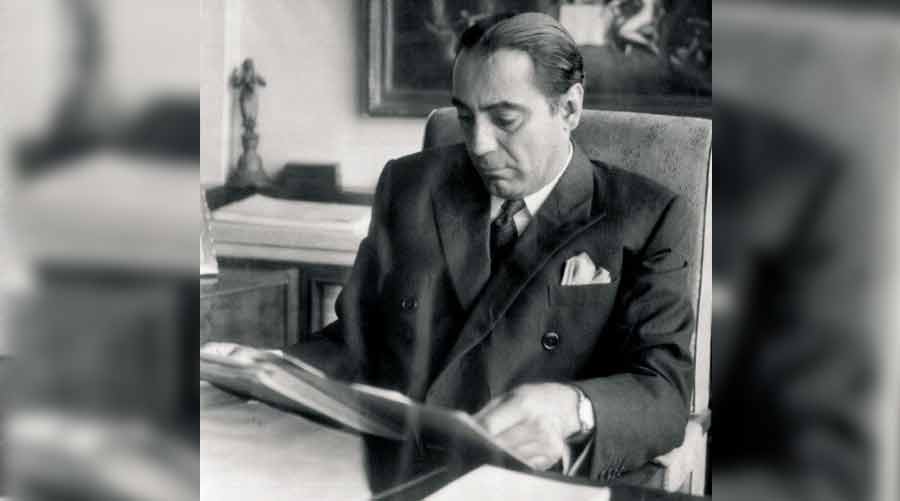

Irrespective of his political views, Bhabha was a man of action TT Archives

Did the nationalist movement and the fervour for freedom from British rule have a big impact on Bhabha, his ideology and his choices?

If one were to join the dots, based on his letters and some other details here and there, some of his ideological beliefs come out, but not very clearly. When he was growing up, he would frequently see nationalist leaders and influential members from all sections of Indian society organise meetings in his house. Individuals, for instance, who came together to form the Bombay Plan and people of a similar ilk. It’s difficult to estimate how much he absorbed from those conversations or just seeing those people around.

As he matured, he identified as a socialist and even quoted Karl Marx in his speeches or lectures. In Cambridge, he came into contact with several Left-leaning scholars, which may have impacted his political views. But, more than anything else, Bhabha believed in the idea of using science for the betterment of the human condition. To that end he tried to settle abroad on many occasions once the Second World War was over, but it never worked out. He wanted to do that because he wanted to make the most of his scientific talent. He had an international perspective and wasn’t jingoistic or nationalistic in a crude, narrow sense. But he certainly was a man of action.

What was the impact of C.V. Raman and his work on Bhabha? Was his the greatest scientific influence or would that be of the American physicist Arthur Compton?

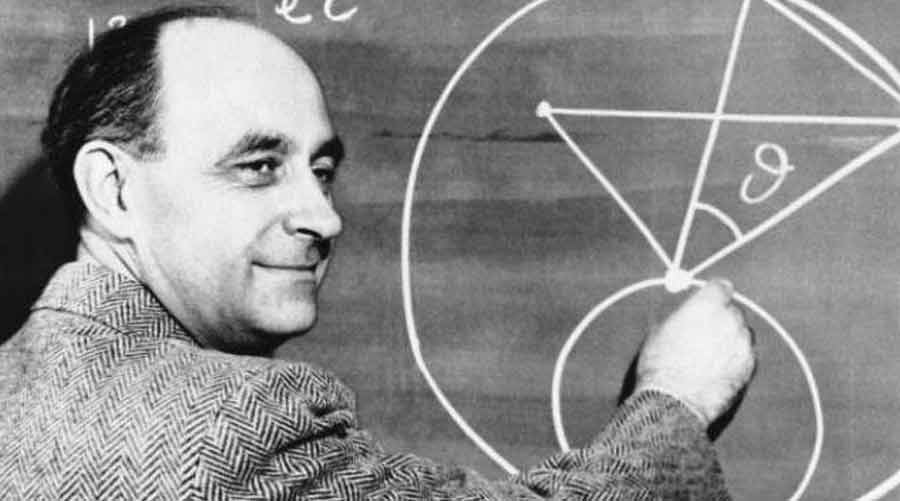

Bhabha and Raman had a lot of mutual respect for each other, and Bhabha must have been impressed by Raman’s ability to create scientific breakthroughs with little resources. But I don’t think Raman had a lot of scientific influence on Bhabha. Compton was different. When he had come to India, Bhabha had listened to his lectures and it did leave a considerable impact on Bhabha. But there was also Enrico Fermi, the Italian physicist who built the world’s first nuclear reactor in 1942 in Chicago. I actually find echoes of Fermi in Bhabha, even though Bhabha met Fermi in Europe and never explicitly mentioned that he was influenced by Fermi.

Enrico Fermi had the most important impact on Bhabha’s work, says Nath TT Archives

Bhabha could rely on Sarabhai; his relationship with Meghnad Saha was complicated

Meghnad Saha and Bhabha rarely got along despite having mutual respect for each other, according to Nath TT Archives

What sort of a relationship did Bhabha share with his contemporaries Meghnad Saha and Vikram Sarabhai? With Sarabhai in particular, did the personal friendship end up having ramifications on the professional equation?

With Sarabhai, Bhabha enjoyed a sense of camaraderie. Both were from successful business families, had somewhat similar outlooks and got along well, even though Sarabhai was junior to Bhabha. Sarabhai charted his own route towards the space programme and also founded the Indian Institute of Management Studies in Ahmedabad (IIMA). But Bhabha and Sarabhai maintained a close connection and were both members of India’s Atomic Energy Commission. Bhabha could rely on Sarabhai. When Bhabha died, Sarabhai took on some of the tasks that were left unfinished by Bhabha. For example, Sarabhai was handling his own space programme and Bhabha’s nuclear programme for a certain period of time.

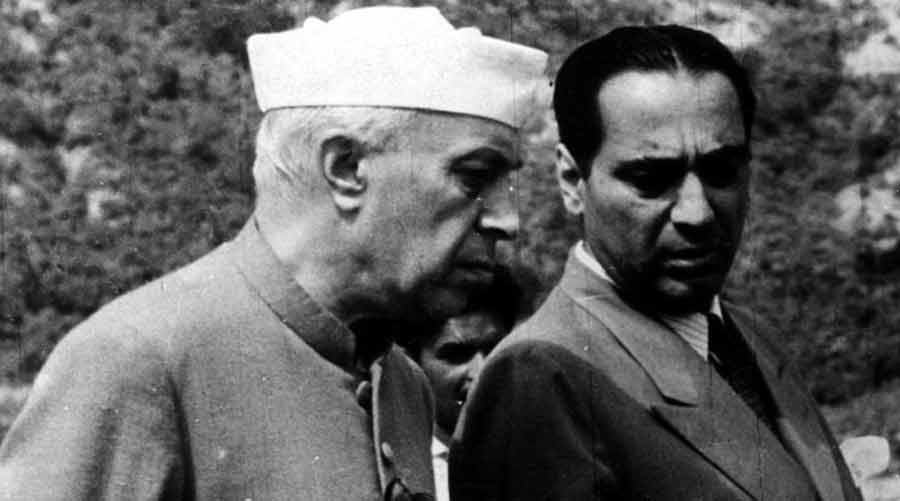

Bhabha’s relationship with Meghnad Saha, however, was complicated. By the early 1940s, Saha had already started working on nuclear physics and had his own institute in Calcutta. He was thinking of how science and technology should be used in post-independent India, but his vision was slightly different (from that of Bhabha). Saha had more of a grassroots approach to scientific research whereas Bhahbha, right from the start, wanted nuclear research to be centralised, that too in Bombay. Eventually, Bhabha’s friendship with Jawaharlal Nehru began to grow and Saha was sidelined. That further complicated the equation between Bhabha and Saha.

Following Bhabha’s death in a plane crash in January 1966, a number of conspiracy theories have come up, one of which suggests that the CIA had a role to play in this since they wanted to paralyse India’s nuclear programme. Is there any credibility to this theory or was Bhabha’s demise a pure accident?

It’s very difficult to say. Yes, there are these conspiracy theories, and frankly speaking, one can’t totally dismiss the possibility. But there’s no hard evidence to back any of this up. So I won’t like to speculate. As far as we know, the plane crash was a result of bad weather, so it may have been an accident. Then again, one never knows for sure.

Bhabha was someone who could get things done

There seems to be a school of thought that Bhabha was an eccentric genius whose presence was intimidating, which meant that he was not always the nicest individual to be around. What is your take on that? How would you assess Bhabha the person?

Based on stories and anecdotes from people who had met Bhabha, I can imagine him to be a person who wasn’t the easiest to be around or work with. From what I’ve heard, he could be distant and aloof with some but at the same time chat for hours in the right company, especially on science. He could only gel with certain types of people.

Was he nice or was he intimidating? At the end of the day, who cares about being nice! Being nice doesn’t bring you a legacy. There are too many nice people around. Bhabha was someone who could get things done.

Bhabha ran India’s nuclear programme like his empire

Bhabha had a close friendship with India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru TT Archives

Throughout Bhabha’s career, his persuasive skills proved just as useful for his success as his scientific brilliance. Could you briefly explain how Bhabha’s ability to convince the Indian political leadership laid the foundation for India’s nuclear programme?

Bhabha’s persuasive skills were very important. He used to exude self-confidence, so just listening to him would often lead people to get easily convinced. On one occasion, he had even convinced the United States Air Force to lend him some planes to help him conduct an experiment. His talent in convincing the Indian leadership was also instrumental in laying the foundation for India’s nuclear programme. He made sure, for instance, that he got his way and that there were no bureaucratic hurdles or delays in his dealings with the different governmental departments like finance. He ran the nuclear programme like his empire, and he was allowed to. Whether that was a good thing or not is a separate matter.

Bhabha is a unique figure in modern history, different from Einstein

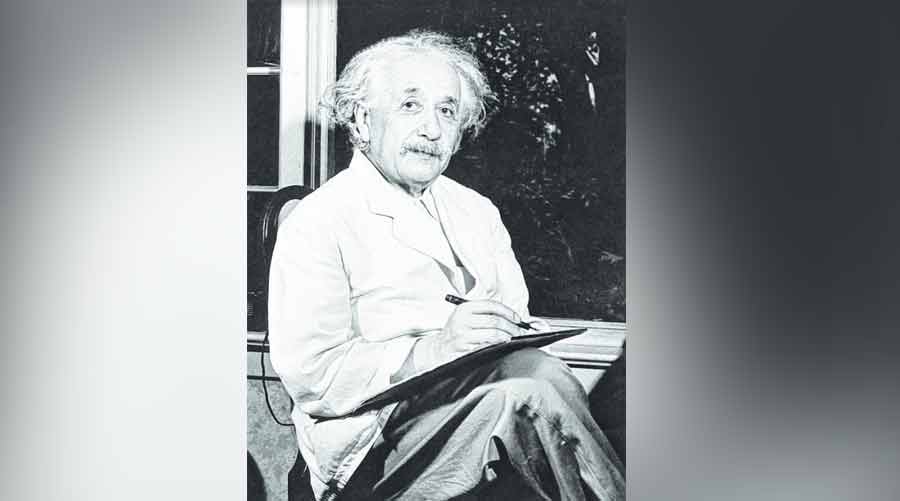

Albert Einstein was not a successful diplomat, unlike Bhabha, argues Nath TT Archives

Would it be fair to regard Bhabha as the Indian equivalent of Albert Einstein?

I don’t think Einstein versus Bhabha is a fair comparison. I don't suppose Einstein was a good diplomat, or even a diplomat at all. He was a very plain-speaking, straightforward person. If you see Einstein’s writings or his commentary, it doesn’t look like something belonging to a seasoned diplomat. But Bhabha was a proper diplomat in that sense, which is also what makes him a unique figure. It’s difficult to find a similar character as Bhabha in modern history.

‘Rocket Boys’ made me cringe; Thank God he didn’t end up opening his shirt and showing off his muscles!

Homi Bhabha (left, played by Jim Sarbh) and Vikram Sarabhai (played by Ishwak Singh) as depicted in ‘Rocket Boys’ Rocket Boys

Have you had the chance to watch the show Rocket Boys, based on the lives of Bhabha and Sarabhai? If yes, do you think the show has done justice to the portrayal of Bhabha? And do you think popular culture is vital to take Bhabha to the younger generation?

I don’t think this is a good way to take Bhabha to the younger generation. Truth is stranger than fiction, and the actual story of Bhabha and the Rocket Boys – whatever that means – was far more dramatic, far more interesting, far more nuanced.

At some point while watching Rocket Boys, I started laughing. At another point, I got really angry. In between, I started tearing my hair, incredulous at what I was seeing on screen. I didn’t know how to react. Finally, I started watching it as flawed fiction. But I also realised that this is how people are going to remember the story of Bhabha, this is how history gets converted into stories or narratives, which is quite unfortunate.

Let me give you some examples of where the show went wrong. They showed Bhabha as a jingoistic nationalist, which was completely out of character. Who gave them the idea that Bhabha went into depression after Hiroshima and Nagasaki? They basically wanted to show Bhabha as some sort of larger-than-life Bollywood hero, such as when he dives into the nuclear reactor. Thank God he didn’t end up opening his shirt and showing off his muscles. Then you look at Sarabhai, who is shown as this dreamy-eyed fool whereas in real life he was extremely charismatic in his own right. And then they changed the character of Meghnad Saha into that of a Muslim!

What this kind of portrayal, as seen in Rocket Boys, does is undermine the importance of scientific effort and intellectual prowess. Every scene of the show made me cringe.

Bhabha received the Padma Bhushan in 1954 and was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Physics on five separate occasions Wikipedia Commons

Do you think Bhabha would have had any regrets, either in matters of his research or with respect to the two main institutions he helped build?

He died quite early (at 56), so he didn’t have the luxury to look back and meaningfully assess his legacy. His life reads like that of a man in a hurry. While I can’t pinpoint any regrets he might have had, I wonder what he would’ve thought of his institutions today or the controversial legacy of atomic energy in India.

Bhabha instilled self-confidence in India’s scientific community

According to you, what should Bhabha be remembered for? What is his biggest contribution to India?

His biggest achievement would be the self-confidence he instilled in the scientific community in an emerging India. Yes, he was an institution builder, but far more importantly, he had the right mix of being a visionary and a practical man, someone who could think far ahead.

Lastly, are you working on any other scientific monographs or biographies meant for popular reading right now?

Not right now. To tell you the truth, I’m not a big fan of biographies of scientists. I’d rather study the history of science and how ideas take shape in the minds of scientists. I’ve worked considerably on the history of how helium was discovered and it’s those aspects that interest me, the forces – scientific, social and political – that precipitate great discoveries.

Nath is more interested in the history of science than in the lives of scientists Courtesy: Biman Nath

Find out more about Biman Nath’s book on Homi Bhabha here.