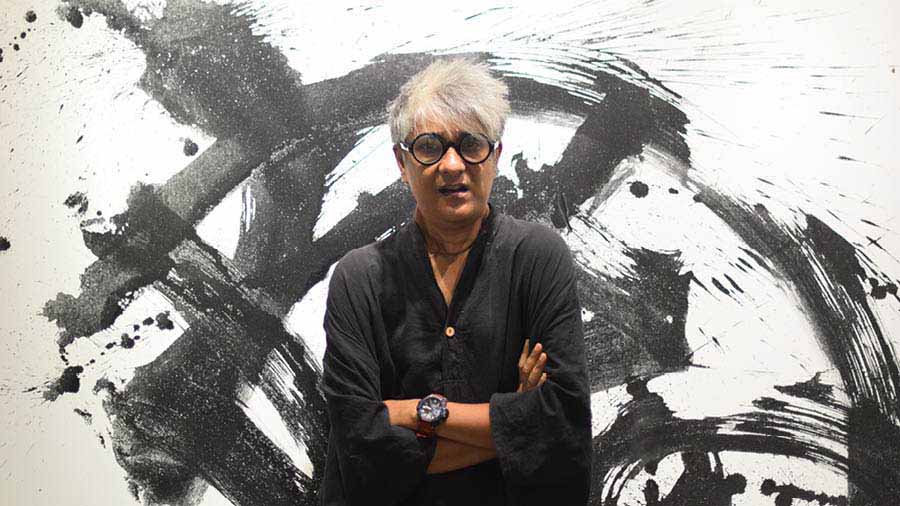

Nilanjan Bandyopadhyay is a multi-talented individual. He’s not only a prolific writer and skilled calligraphy artist, but also a scholar on Rabindranath Tagore and Japan. He’s the creative force behind Kokoro, a home with Japanese-inspired design that’s become a popular spot for art and aesthetics enthusiasts.

My Kolkata got in touch with the author for a freewheeling chat on his books, his thoughts on Tagore, the impact of Japan and the Japanese style of living in his life, Kokoro and more. Edited excerpts from the conversation follow...

My Kolkata: Tell us about your book Imagining Japan In Santiniketan.

Nilanjan Bandyopadhyay: I have a small house named Kokoro in Santiniketan. Imagining Japan in Santiniketan is a brief history of the house. It is a very personal book which deals with the reason behind building Kokoro, the philosophy and idea behind it, the reason behind making it, people who have been involved with it and a few other relevant things with pictures of the house.

There is another book that recently was published — Ochena Moumachit Jonmodin, Kokoro’r Kobita. I have written around hundred poems on Kokoro, its surroundings, nature and realisations I have had. The book is a collection of those poems.

Tell us a little about your other book, In the Cause of Friendship.

Rabindranath Tagore forged a significant bond with the Japan consulate. Pinpointing the exact duration of Tagore’s affiliation with the Japan consulate proves challenging. Established in Kolkata around 1907, records of correspondence between Tagore and the consulate extend only until 1929. Yet, there are references to connections being established as early as 1916. The book delves into the correspondence shared between Rabindranath and the Japan Consulate, focusing predominantly on the years spanning from 1929 to 1940.

Tea room in Kokoro Nilanjan Bandyopadhyay

As a Japan enthusiast, and having lived in Japan, how do you see the Japanese influence in your life?

India shares a rich and prolonged connection with Japan, and I find the cultural and aesthetic traditions of Japan very powerful. This influence can be attributed to the transformative collaboration between Rabindranath Tagore and Okakura Kakuzo, after whom Kolkata’s Okakura Bhawan is named. This partnership sparked a movement, drawing Japanese artists, artisans, and Judo experts to India, leaving an indelible mark on our traditions. Growing up in Santiniketan, my deep-rooted love for culture and aesthetics only flourished further. Anticipating a longing for Japan upon returning to Santiniketan, I decided to create a home, which I affectionately named Kokoro, in the style of a traditional Japanese house. It serves as an illusion, offering a glimpse of Japan right here in Santiniketan.

I never aspired to adopt a Japanese identity, but rather sought to embrace their spirit and heritage, incorporating their practices into my own way of life. I believe these elements possess a universal appeal. I have internalised and amalgamated a few things with my own cultural heritage. One integral part of this way of life is Bodhi Chaa (Bodhi Tea Ceremony).

I’ve often pondered over our way of having tea, which seems rooted in colonial practices. In our country, tea is undeniably a part of commerce, a driving force for business and revenue. Yet, it holds a spiritual and cultural significance that we tend to overlook. Unlike countries like China, Korea, Taiwan, or Japan, where tea rituals bring people together for meaningful conversations in a serene atmosphere, Tea has never been taken seriously in India.

However, we have our cha-er adda, where conversations flow over cups of tea, and we even consider it a sort of nesha or addiction. Personally, I’ve ventured into creating an Indian tea ceremony. I don’t shy away from the fact that my home has become a public space because, to me, anything truly good is meant to be shared universally. This has been a sort of cultural experiment for me. I see it as a way of contributing to humanity.

My deep appreciation for haiku, calligraphy, and the tea ceremony clearly reflects a profound Japanese influence in my work. It’s a fusion of cultures that resonates deeply with me.

What does Rabindranath Tagore signify in your thought process and life?

While my writings aren't directly influenced by Rabindranath, I can't deny his impact on me. During his five visits to Japan between 1916-29, he delved into calligraphy, adopting the Japanese approach. Although this didn't directly shape my calligraphy, I can't deny the presence of his thoughts and teachings within me.

If you ask me what are those few things of Rabindranath Tagore that have influenced me, the first and foremost is the desire to express myself. His mantra was, ‘prakashito hou’ (express yourself). Often, we navigate through complexities and overlook what truly matters to us. Suppressing these desires can lead to pent-up feelings of anger, frustration, or even depression. I think living in the ashram has made me creative and expressive. The Santiniketani shiksha (education) has given me a huge opportunity to express myself, through calligraphy or poetry.

When it comes to poetry, I have a special fondness for Rabindranath’s short poems. During his time in Japan, one of his interests was delving into Japanese literature. However, the available writings don’t truly showcase his mastery of haiku poems. He once eloquently stated, “These Japanese poems are not for songs, but to see as images.” If you've perused my poems, you'll notice they fall under the category of imagist poetry - rich in vivid imagery.

I'm not a frequent attendee of poetry readings mostly because I don’t think my poems are the kinds that can be read. They are to ponder upon, to relate with. They come to me like a sudden bolt of inspiration, not through deliberate writing or imagination. These poetic moments strike me, sometimes in dreams, other times in the midst of observing a scene. These encounters occur daily, and I refer to them as my moments of poetic inspiration. They might seem small, but I find great joy in contemplating them, as they offer me a profound understanding of life.

One day, I saw a tree whose top was burnt, but there were people standing beneath it for some shade. This is a realisation. Our lives have become too materialistic. If you ask me what happens if I think of these things, I’ll say looking at that tree and the realisation I get helps me relate to others around me. The poems I write come from my life.

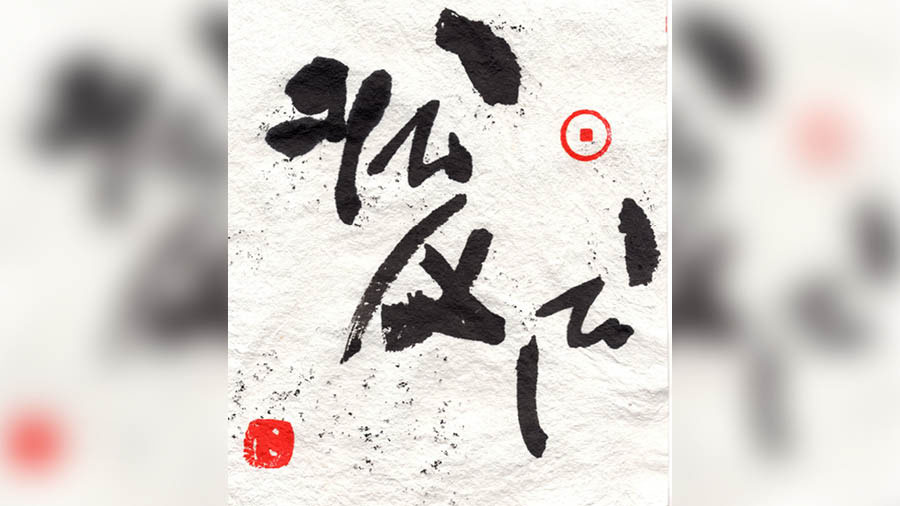

A calligraphy titled ‘Elo Melo’ by Nilanjan Bandyopadhyay Nilanjan Bandyopadhyay

How did calligraphy and poetry become such significant forms of expression for you? They seem to hold a special place in your creative journey...

I have loved writing since I was a child. I wanted nice pens and experimented with my handwriting. But, my way of seeing things changed entirely when I went to Japan because I met many master calligraphers there, and I saw them write. Those bold lines on a white space expressed immense energy. In Japan, I saw how beautifully a mother tongue was being expressed through calligraphy. In our country, we don’t hang calligraphy on the walls. We mostly perceive them as graphic art, used on book covers, hoardings or in letters. We haven’t yet been able to develop calligraphy as a form of art. That perhaps is because the calligraphy in Japan has come from pictographs. Hence, their calligraphies have a pictorial element. I thought if I use Japanese ink and brushes and write in Bengali, it would look beautiful and an energy will flow through them. The spontaneity in calligraphy brings out what is in me.

Many noted names have been to Kokoro. Any memories related to Kokoro that come to your mind?

Painter Jogen Choudhury, actor-director Aparna Sen, filmmaker Gautam Ghose, Chinese painter Xu Beihong (Ju Péon) and his daughter, who also played piano at Kokoro. She also sent ink for me from China. Many people from Japan have visited and they still do. One of them gave me a Japanese herb, called Mitsuba. Jogen Chowdhury once came here and painted three artworks. I think the creative space in this house attracts them.

Painter Jogen Chowdhury in Kokoro, Santiniketan Nilanjan Bandyopadhyay

Could you please explain more about the chosen colour palette of the building?

Kokoro’s colour palette stems from my stay in Japan and the colour palette that left an imprint on me. It is also surrounded by greenery. Kokoro makes me feel like I am living in a city, but it is deep in the mountains. The colour palette is based on the Japanese concept of wabi sabi — its simplicity and the sadness, incompleteness and imperfection, withstanding the test of time. Another interesting facet of this house is how light plays in it. In Kokoro, darkness is very important. The way shadows or the diffused lights in the house leave an effect, the way light moves from one part of the house to the other, Kokoro responds to that.

Bodhi Tea essentials Nilanjan Bandyopadhyay

Minimalist decor, use of ceramic, planned garden, calligraphy, piano, ikebana — what was the planning process like?

I do kintsugi. There was a time in life when I suffered if things I cherished got broken. But now I know broken things can be beautifully put back together. And the reformed version often is more beautiful than the original one. An artist from Japan sent me a kintsugi kit. I use that to conjoin broken pieces. The philosophy also applies to our lives too, where we can mend what’s broken.

Kokoro has been built with the tea room at the centre of the house. Here, the main activity is tea. The places that have inspired me have had tea at its centre, around which creativity has evolved. Especially in Japan, tea at the centre has given birth to poetry, calligraphy, flower decoration or gardening. Garden is an important component of the tea culture. It has also developed an experimentation on ceramic. My poems, cooking, taking care of the cleanliness, or my calligraphy stem from Kokoro. Kokoro is not a house, it is a way of life.

You often share glimpses of Kokoro. Tell us about the concept and the reason behind building it.

The inspiration behind building Kokoro stemmed from my deep longing for Japan. I yearned for a sanctuary in India that could transport me there. Kokoro is kind of a creative illusion of Japan. The activities that I liked doing in Japan, I can do them here. Moreover, I wanted to create a space for people in Japan who had once given me shelter. Many of my friends from Japan are now in Santiniketan, they are abashiks (resident students of Visva Bharati university), I have made Kokoro for them too.

Which is your favourite part of Kokoro? Can you please define the style of living in Kokoro?

Kokoro does not have many rooms. There are two rooms where you can stay. The first-floor room, though small, holds great significance. It features a sliding door and a comfortable bed. This space holds a special place in my heart as it was once occupied by my father. The memories of him are deeply intertwined with Kokoro. For me, it's a place of solace, a place where I can still sense his presence, his unique energy. My father used to say he experienced restful sleep in that room, and interestingly, I too find a profound sense of tranquillity when I sleep there.

Ikebana by Nilanjan Bandyopadhyay in Kokoro Nilanjan Bandyopadhyay

What are your future plans for Kokoro?

Many people have written their thoughts on Kokoro upon their visit. I want to do a coffee table book. A book on Bodhi Tea is also getting published.