On the verge of completing 76 years of Independence, the India of today is home to glittering metropolises, an array of start-up unicorns, the world’s most prolific film industry as well as cricket’s most popular team and league. All this while India, simultaneously, remains home to everyday discrimination on the basis of the caste system, one of the most enduring forms of systemic prejudice practised by human beings.

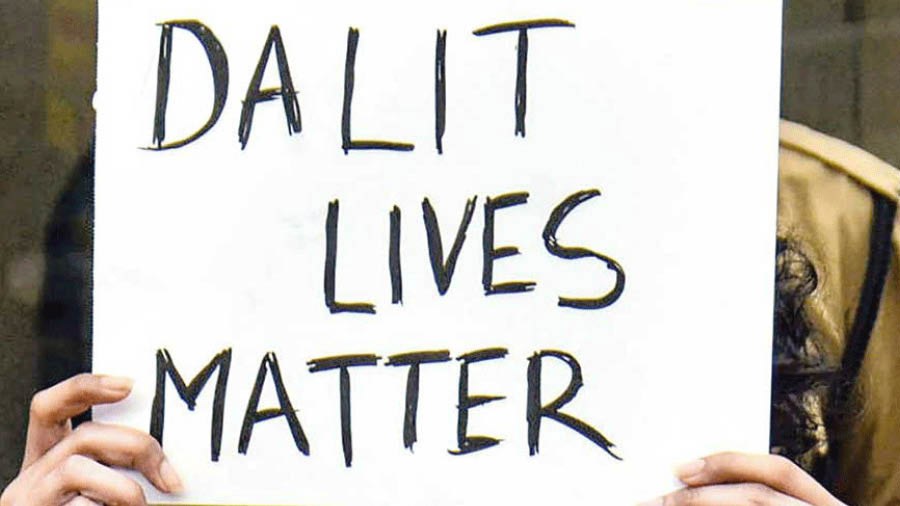

Across 2020 and 2021, more than one lakh cases of caste violence were registered in India. Notwithstanding the fact that caste discrimination has long been legally outlawed in the country, the social and political realities of caste remain as pertinent and pernicious as ever.

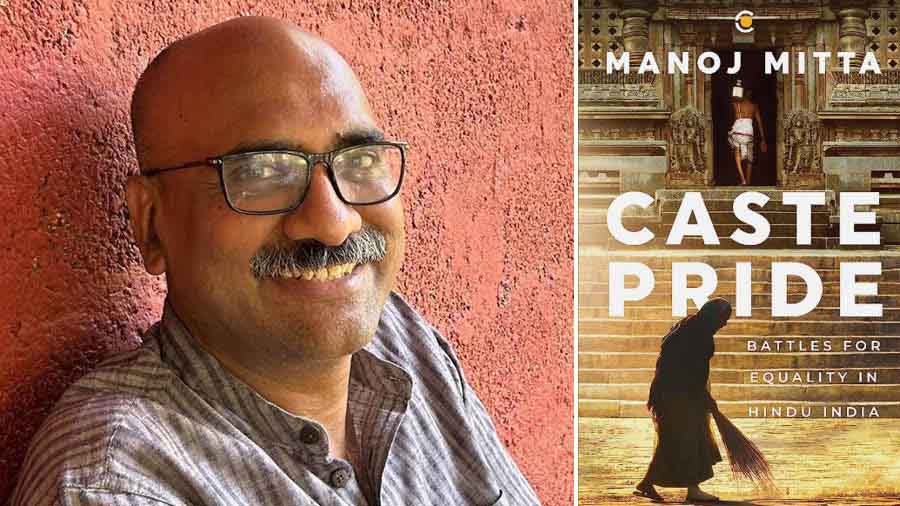

In Caste Pride (published by Context, an imprint of Westland Books), written by Delhi-based journalist, Manoj Mitta, there emerges for the first time a thorough account of the relationship between caste and law in India. Alongside are numerous stories of how caste has been confronted, challenged as well as co-opted by politicians, reformers and the judiciary since the 19th century.

My Kolkata caught up with Manoj over video call to discuss how he came to write the book, the contrasting methods of Ambedkar and Gandhi on caste reform, how caste discrimination can be eliminated and more. Edited excerpts from the conversation follow.

‘Who could have imagined that Motilal Nehru was capable of taking a shockingly regressive position on sati’

My Kolkata: What made you write this book? And what was your approach behind it?

Manoj Mitta: I have written this book essentially as a reporter, as a journalist who has worked closely on the subjects and issues of law and social justice. I’m not theorising or presuming to be an academic in writing this book.

The book came out of my contemporaneous pursuit of studying violence against Dalits. Why is there so much impunity regarding caste violence and why is it still so deeply ingrained in Indian society, despite all the rhetoric about equality in the Constitution? Once I started probing these questions, I repeatedly ran into some arm of the State or the other betraying caste prejudice or structural bias. I discovered a wealth of previously unseen judicial and legislative records going back two centuries. In doing so, I arrived at new material that was hidden in plain sight in the archives, at a virgin territory containing an intersection of law and caste.

My book has several great stories to tell, stories that vindicate both sides of the debate on caste, people on both the left and the right. For instance, who could have imagined that Motilal Nehru was capable of taking a shockingly regressive position on sati, or that his son, Jawaharlal Nehru, hardly opened his mouth on caste laws in Parliament or in the Constituent Assembly? I show how the battle between Hindu liberals and conservatives on caste has often unfolded through arguments citing the same scriptures with different interpretations. I have several accounts of heroes who had feet of clay as well as unsung heroes who deserve more recognition.

The fact of the matter is that as a country we have been able to shake off the yoke of colonial rule, but not that of caste. The assumption that modernity would help us overcome religiously-sanctioned prejudices has been belied. That is what my book sheds light on. However, in approaching it, I haven’t done so as a pundit or an expert on caste. My approach is that of a kathavachak or a storyteller.

Is caste a fundamental and irrevocable aspect of Hinduism?

Caste is endemic, not merely confined to Hinduism or India. But there is no religious origin for caste that can be traced in communities other than Hindus. Caste is present not just in smriti, but also in shruti, like the Vedas. It is central and organic to Hindu religion, practice and customs. The battles on caste that have been fought in Indian legislatures and courts have predominantly been fought between Hindus. To my knowledge, there have been no instances of caste disputes or major debates from other religions going to courts.

‘Caste violence has never really been exploited for political mileage, unlike the use of communal violence’

Caste violence has never produced political gains for the aggressor in India TT Archives

Your book elaborates on the issue of caste-based violence, highlighting several such instances across Indian history. You have written on mass violence before, be it the anti-Sikh pogroms of 1984 in When a Tree Shook Delhi or the 2002 Godhra incident in Modi and Godhra: The Fiction of Fact Finding. Are there certain aspects of caste-based violence in India that make it distinct and, perhaps, more problematic than other forms of communal or sectarian violence?

One big distinction is that there’s no special law relating to communal violence in India. An attempt was made during Manmohan Singh’s regime to have a bill on communal violence and create a chain of command for responsibility, wherein one can’t just be looking at the accountability of foot soldiers for large-scale violence, but will also have to look at a potentially structured higher order that has been encouraging or sanctioning the violence. But the bill fell through, not least due to vehement opposition from the BJP.

When it comes to caste violence, a special law called the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act was passed in 1989. In spite of that, there remains so much impunity when it comes to caste violence, even though many have called this law too stringent, even draconian, in the manner of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA).

The other distinct feature of caste violence is that it has never really been exploited for political mileage, unlike the use of communal violence. In 1984, the Congress used the anti-Sikh pogroms to help obtain a brute majority under Rajiv Gandhi, the kind of majority they did not even enjoy under Nehru or Indira Gandhi. In the wake of the Babri Masjid demolition in 1992, the BJP and the Shiv Sena joined hands in Maharashtra for the first time to do something similar. Another example of this is what happened in Gujarat in 2002, when Narendra Modi’s electoral popularity surged in the aftermath of the Godra violence, to the extent that he came to be known as Hindu Hriday Samrat. No such thing has happened with caste. For instance, there have been repeated instances of caste violence in Bihar, particularly by an upper caste militia called the Ranvir Sena. But that has not ensured any major political gains for the Bhumihars, who formed the Sena in the early ’90s.

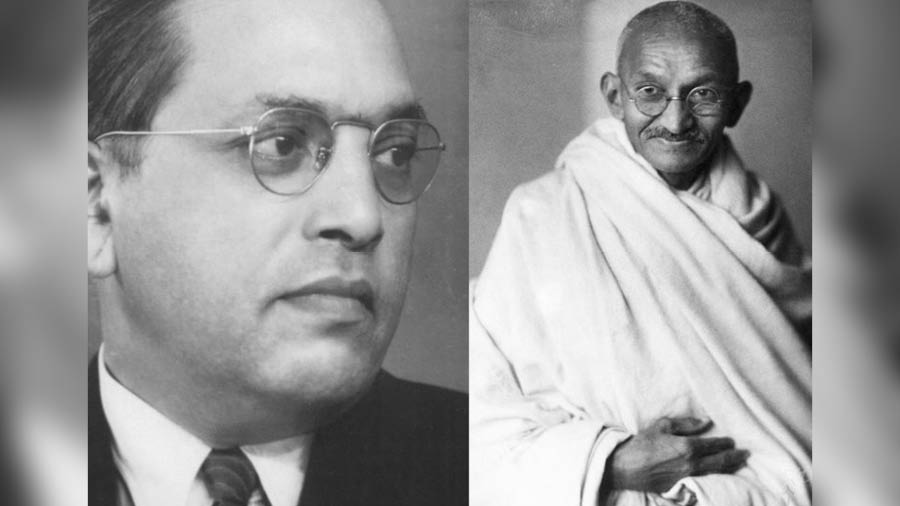

Ambedkar had a radical, rights-based approach to caste; Gandhi, as a mass leader, was more conservative

BR Ambedkar and MK Gandhi were starkly different in dealing with caste discrimination, as argued by Manoj TT Archives

Most historical discussions of caste in India revolve around two personalities, MK Gandhi and BR Ambedkar. Can you briefly compare their ways of tackling caste reform and what made them so different from one another?

Gandhi and Ambedkar were political contemporaries, who were constantly battling with one another, not least on caste.

What has been overlooked by experts is that when you analyse Gandhi through the lens of law, the nature of his politics vis-a-vis caste becomes much clearer. Many historians have mistaken Gandhi’s support for the Vaikom Satyagraha (a non-violent agitation between March 1924 and November 1925 to obtain access to the prohibited public environs of the Vaikom Temple in Travancore) as evidence of Gandhi being open to temple entry for Dalits. That’s far from true. For years, Gandhi unabashedly took the position that Dalits could not enter temples, because the common custom across India was that only Savarnas (including OBCs) could enter, not Avarnas (Savarnas fall under the four varnas of Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya and Shudra, as enshrined in the caste system; Avarnas lie outside the varnas). It was only after the Poona Pact (in 1932) where Gandhi had forced Ambedkar and his supporters to concede on the issue of separate electorates for the depressed classes that he felt the moral responsibility of a reciprocal gesture to draft a resolution and secure greater rights for Dalits. But even then, on temple entry, Gandhi still advocated for persuasion over any legislative measure, at least until Hindu society was ripe for the enactment of any such laws. To this end, he encouraged referendums among local Savarnas on the issue of temple entry for Dalits and one such referendum was carried out in Kerala.

Ambedkar, for his part, was initially interested in temple entry. He even led the temple entry movement in Nasik, but was disenchanted by pushback from orthodox elements. Gradually, he pivoted to focus on education, access to public amenities, securing government positions and the like. Ironically, he stopped engaging with temple entry at the very time when Gandhi was taking it up proactively. But, distinct from Gandhi, Ambedkar’s was a rights-based approach, which could be much more radical. On the other hand, Gandhi, as a mass leader, could never go too far ahead of what the community was prepared for. That made Gandhi’s approach to caste more conservative, even regressive.

Your book talks about the role of two women, Amrit Kaur and Hansa Mehta, in tackling caste discrimination and other social ills through Constitutional amendments. Can you give us some more examples of unsung heroes on caste reform?

In 1916, a relatively unknown Parsi legislator called Maneckji Dadabhoy took the initiative in discussing untouchability for the first time in the Indian legislature. He broke the silence of India's parliament (under the British) on untouchability. There were many who opposed him tooth and nail, including the likes of Madan Mohan Malaviya and Surendranath Banerjee.

Two years later, in the same legislative body, Vithalbhai Patel (elder brother of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel) introduced the first-ever bill seeking to legalise intercaste marriage and ensure that the children of such marriages were not considered illegitimate.

In 1926, a Dalit from Madras, named R. Veerian, initiated the bill that would pass as the first-ever legislation in the country (albeit at the provincial level) against untouchability. There are scores of more such stories in the book, of heroes who haven’t had the recognition they deserve.

‘Even though our current Prime Minister belongs to a backward caste, our democracy still remains in thrall to caste’

Manoj agrees that political parties have tended to exploit caste divisions in their electoral strategies TT Archives

Since Independence, there is no doubt that India has become less casteist. At the same time, caste remains an everyday reality for millions of Indians and is frequently weaponised as an electoral issue. How can this change and what are the biggest challenges?

The biggest challenge is attitudinal. It’s to recognise that the struggles waged by equality champions to overcome caste discrimination predated the freedom struggle and carry on even after decolonisation. Far from seeing themselves as vehicles to take forward caste reforms, political parties across the board have tended to exploit caste divisions in their electoral strategies.

Caste debates in courts and legislatures since colonial times show that even the Hindutva approach of consolidating Hindus, irrespective of caste, is unlikely to annihilate caste. For, as Ambedkar pointed out, caste is so resilient because of the scriptural sanction enjoyed by varna. There cannot be enough political incentive to bring about caste reform until dominant castes have any inclination to make Hinduism compliant, in letter and spirit, with the Constitutional values of liberty, equality and fraternity. This is evident from the fact that even though our current Prime Minister belongs to a backward caste, our democracy still remains in thrall to caste.

Lastly, you have revealed before that there will be a second volume of Caste Pride. What will that deal with?

It will focus on many of the other aspects of caste that I did not have the scope for in this book, including the topic of reservations and affirmative action. I’ll also take up inter-caste marriages and show how they still lead to honour killings in India.