Bengal’s history and heritage have been documented and eulogised for generations. And yet, in discussions on what makes Bengal distinct, art and architecture have rarely received their due. In his own way, Amit Guha is on a mission to change that. My Kolkata caught up with Amit, who has been busy working in the e-commerce space in the UK – in leadership roles at Marks and Spencer (M&S) and then Zapp – and has prior experience in consulting, for a roadmap to understanding Bengal’s art and architecture.

Edited excerpts from the conversation follow.

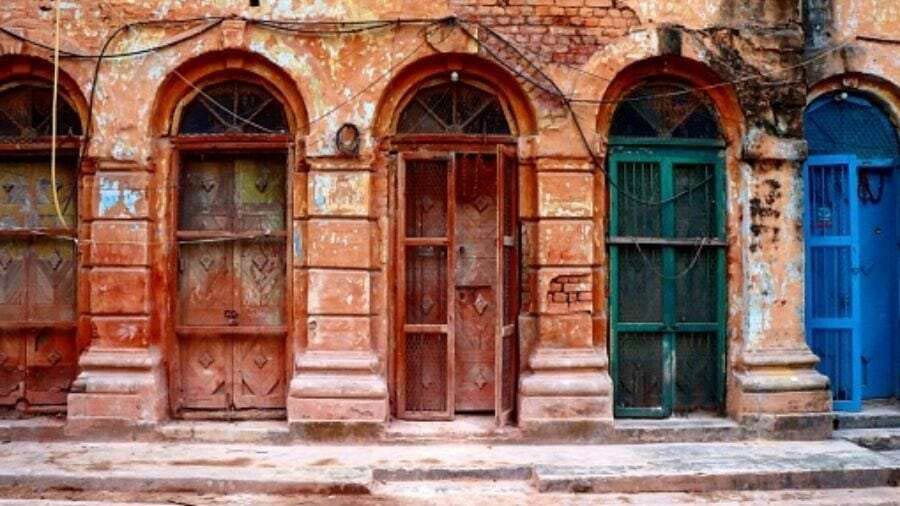

Colonial-era buildings of north Kolkata, art-deco buildings of south Kolkata

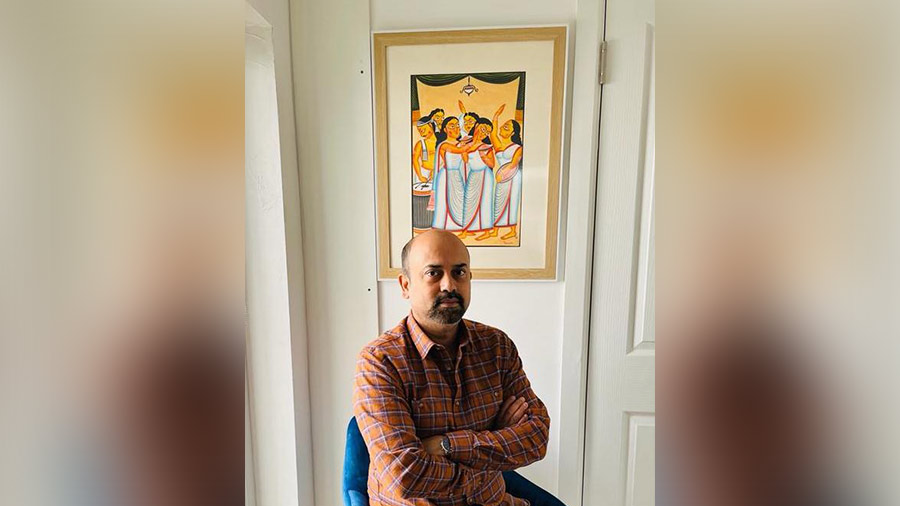

Amit tries to return to Kolkata every year around Christmas Amit Guha

My Kolkata: What are your best memories of growing up in Kolkata? How often do you return to the city these days?

Amit Guha: I spent my early childhood at Rishra in Serampore and my teenage years in Ballygunge and Salt Lake. Memories of Rishra are of large, open playing fields where we played football, cricket, and badminton, and the swimming pool in which we spent many hours in the summer. Ballygunge and Salt Lake were different – less playing in fields and more meeting up with school friends for adda, food and walking around in the streets.

I visit Kolkata at least once a year, usually around Christmas, and in some years I’ve managed to visit two or even three times.

Do you still have a lot of family and friends in Kolkata?

My mother lives in Salt Lake and my in-laws in Deshapriya Park. Most of our relatives are in south Kolkata. Some of my friends from Calcutta Boys’ School and IIT Kharagpur are also in Kolkata, and I make sure to meet as many of them as possible.

Walking around Kolkata and sampling its buildings, both old and new, is one of Amit’s favourite pastimes in the city TT archives

What are your favourite things to do/places to visit/eat-out places whenever you are back in Kolkata?

I like waking up early and walking around the streets, discovering and photographing colonial-era streets and buildings of north Kolkata and art-deco buildings of south Kolkata. I also like visiting museums. The Indian Museum, of course, but also the less-visited ones such as the Asutosh Museum of Indian Art in College Street, the State Archaeological Museum in Behala, the Gurusaday Museum in Diamond Harbour, the Birla Art Museum on Southern Avenue and the Sahitya Parishad in Maniktala. Food also remains high on my agenda. Regular fixtures are Paramount, Putiram, Nizam’s, Nahoum and Sons and Flurys, with breakfast at Gupta’s or Maharani.

But my visits aren’t just about Kolkata. At least five days every year are reserved for travelling out to the districts to see architectural sites and terracotta temples, mosques and tombs. In the last 15 years, I’ve been to more than 200 villages across West Bengal and Bangladesh.

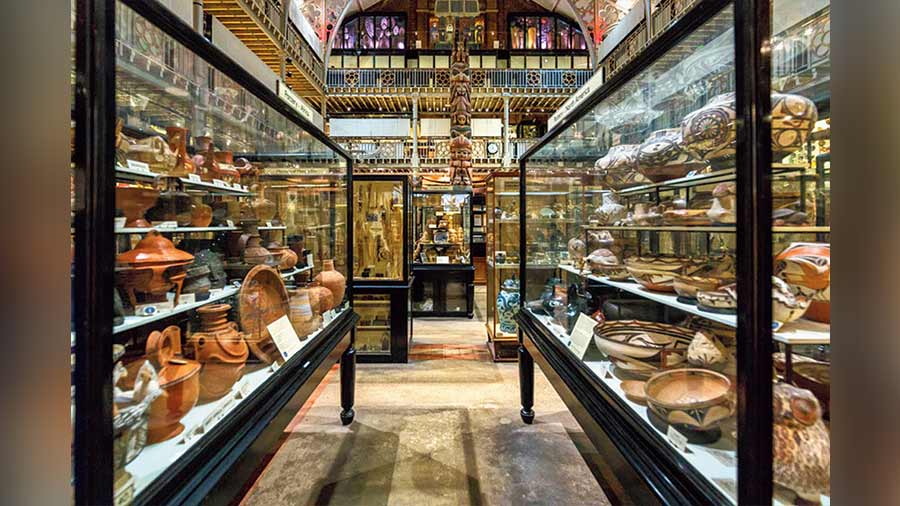

London and Kolkata are both visibly oriented towards cultural pursuits

Amit feels that both London and Kolkata are visibly oriented towards cultural pursuits British Museum

You have lived in various cities across your career, from New York to San Francisco, from London to Seoul. Have any of these cities reminded you of your time in Kolkata?London, of course! It reminds me of Kolkata in so many ways. The feel of the city, with its narrow cobbled streets, grand Victorian buildings, museums, and public spaces. Both cities are visibly oriented towards cultural pursuits with film festivals, musical performances, art exhibitions, and even Durga Puja in autumn!

There are many more indirect reminders. After all, the cities have a deep, centuries-old connection. Many objects in the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum were “acquired” by the British in Kolkata, such as Hindu (Pala/Sena and Orissan) sculpture from the collection of Major General Charles Stuart, a very interesting character whose Persian-style tomb is in the Park Street Cemetery. There are also reminders in the form of exhibitions that are linked to Kolkata and Bengal. The recent Tantra exhibition at the British Museum had a section devoted to Tantra as practised in Bengal (the showpiece was a clay Kali murti made in Krishnanagar). Another popular exhibition, “Forgotten Masters” at the Wallace Collection, was devoted to Indian painters such as Sheikh Zainuddin, Bhawani Das and Haludar.

Calcutta Boys’ and IIT KGP, ISB and SOAS

IIT Kharagpur allowed Amit to explore a number of extra-curricular activities, including swimming TT archives

How formative was your time at Calcutta Boys’ School and then at IIT Kharagpur, where you completed your BTech in Computer Science? To what extent did these institutions shape your career and identity?

At Calcutta Boys’, I remember we had some great writers and actors, and we spent as much time talking about Shakespeare and Ray as about physics and maths. We entered creative writing contests at fests and also the Maths Olympiad. My IIT batchmates also had a range of talents and interests, and the institution gave us the opportunity to pursue many activities outside academics. I edited the IIT literary magazine Alankaar and was on the IIT KGP swimming team. In general, I remember spending far more time on extra-curricular activities than studying! It’s hard to deconstruct their influences on my career and my world-view, but the opportunities that these institutions provided definitely gave me the confidence to broaden my interests, to take risks, to veer off the beaten career track and chart my own path into domains that I’m genuinely interested in and passionate about.

Amit completed his postgraduate course in Indian art from SOAS University of London SOAS

You have a Master’s in Science from the State University of New York, an MBA from the Indian School of Business (ISB) in Hyderabad, and a Master’s in Indian Art History from SOAS in London. What explains your varied academic interests and pursuits?

After finishing my Master’s in Science, I started working in California in the early 2000s, but realised quickly that the prospect of a purely technical career didn’t enthuse me. I returned to India to do an MBA at ISB, where some excellent professors opened my eyes to the field of operations research, which I found fascinating, as I could use my computer science background to solve real-life business problems. My interest in Indian art and architecture started with my travels while living in Bengaluru, but only over the last decade has it developed into a passion. London has been a great place to pursue this as it has dozens of auctions, exhibitions, and lectures on Indian art every year, is home to some of the finest scholars of Indian art history and has some of the finest collections of Indian art in museums and galleries. The SOAS postgraduate course in Indian art, which I completed while working full-time, has added some academic grounding to my several years of independent research in the area.

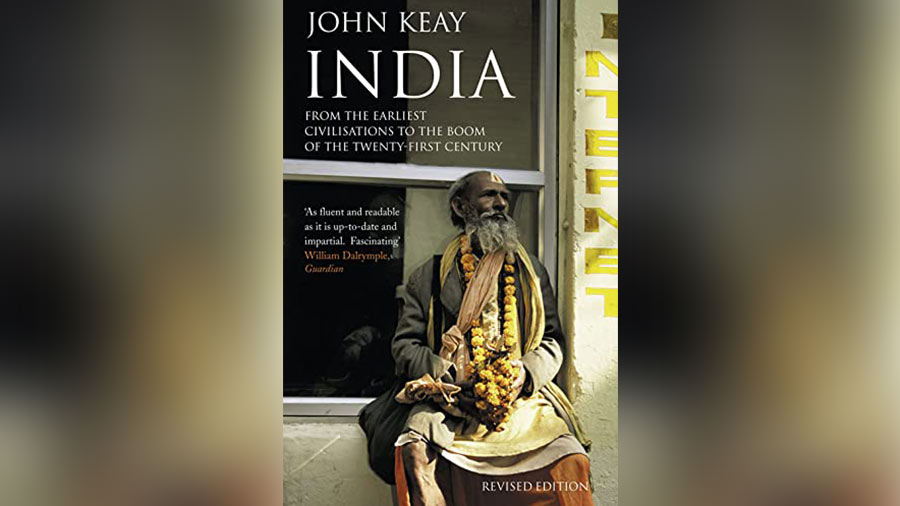

John Keay’s ‘India: A History to Brick Temples of Bengal’ by David McCutchion

John Keay’s ‘India: A History’ acted as the catalyst behind Amit’s interest in Indian architecture

How did you develop an interest in Indian art and architecture?

I became interested in Indian architecture quite suddenly. In 2002, after reading John Keay’s excellent book India: A History, I went on a trip from Bengaluru to see the capitals of the major Deccan sultanates: Vijayapura, Bidar and Hampi. I went for history but came back amazed by the architecture. The next weekend, a friend and I went to see the Hoysala temples of central Karnataka, and were mesmerised by the intricate, jewel-box temples. Over the next two years, I read whatever I could find on Indian architecture, and with George Michell’s Southern India handy, I visited more than 30 sites across Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh.

Since 2005, however, my architectural travels and research have been almost entirely focused on Bengal. It started with a trip to Bishnupur in 2004, seeing terracotta temples and becoming enchanted by their architecture, sculpture, and iconography. There are not many books on Bengali architecture, but I managed to find some of the Jela Purakirti Series, and the seminal Brick Temples of Bengal by David McCutchion, and started exploring. Since then, I’ve been on more than 70 trips and photographed over 350 brick temples, mosques, and tombs across West Bengal and Bangladesh. In 2004, I started the Facebook Group “Terracotta Architecture of Bengal” and through this group I’ve met many terracotta researchers and enthusiasts who are doing remarkable work.

Joy of exploring the many schools and strands of Indian art

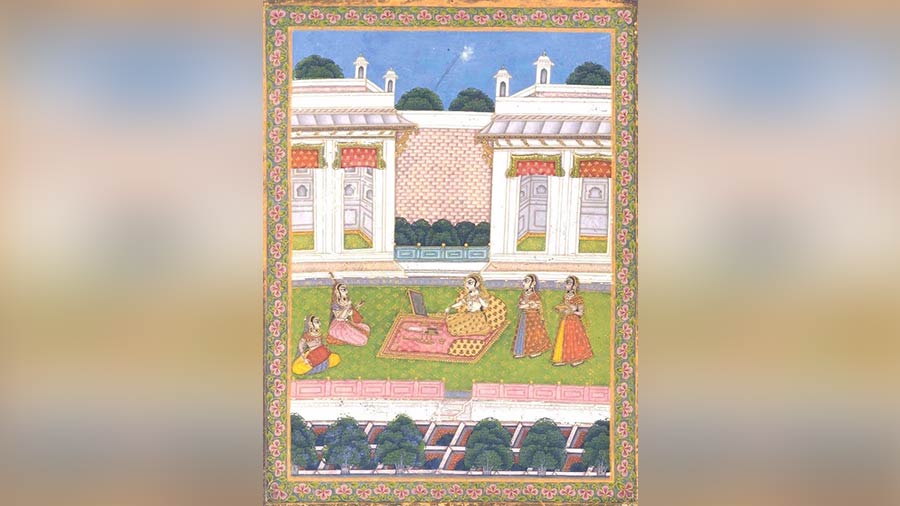

The ‘Vasak Sajja Nayika’, a part of Amit’s family collection of art Amit Guha

You have built quite an extensive family collection of Indian/Bengal art over the years. Could you take us through some of the most notable artworks in your collection?

For me, collecting is less about ownership and more about the joy of exploring the many schools and strands of Indian art. I suppose collecting art is an unusual hobby among Bengalis today, but until the early 1980s, there was a great tradition of collecting and scholarship in Kolkata, among Bengalis such as Gurusaday Dutt and Asutosh Mukherjee and Marwaris like G.K. Kanoria and B.K. Birla. Most of the objects in our collection were acquired at auctions in the UK, Europe, US, and Australia, and some modern and folk art directly from the artists. Our collection has paintings and objects from many regions of India but we are, of course, partial towards Bengal. Some of my personal favourites from Bengal are:

- Vasak Sajja Nayika, a miniature painting from Murshidabad from about the 1740s, showing a nayika dressing up while being entertained by musicians. She is seated in a pavilion with gardens in front and buildings behind. I like this painting for its composition, its borders, the symmetrical gardens, the elaborate architecture, the varied poses and dresses of the figures and their distinctive Murshidabad eyes.

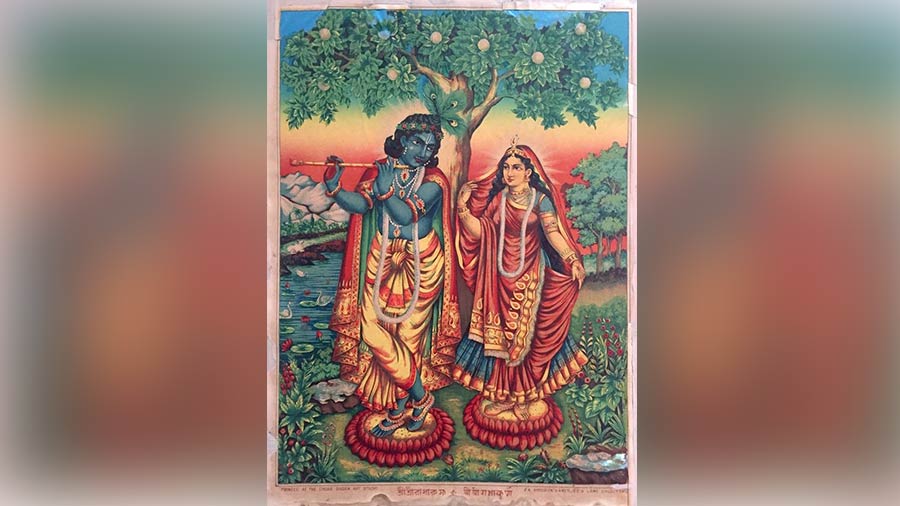

The lithograph depicting Krishna and Radha is another of Amit’s favourites from his collection Amit Guha

- Sri Sri Radha Krishna, a lithograph printed in the 1890s at Chorebagan Art Studio. Radha and Krishna wear elaborate dresses, garlands and jewellery. They stand on lotus flowers beneath a kadamba tree. A river flows behind them, around them are flowering trees in a lush meadow.

Murshidabad’s ivory elephant procession Amit Guha

- Statue of an ivory elephant procession, from Murshidabad, made sometime in the 19th century. A richly caparisoned elephant carries a decorated howdah with two passengers. The mahout sits in front and the platform has footmen in the four corners.

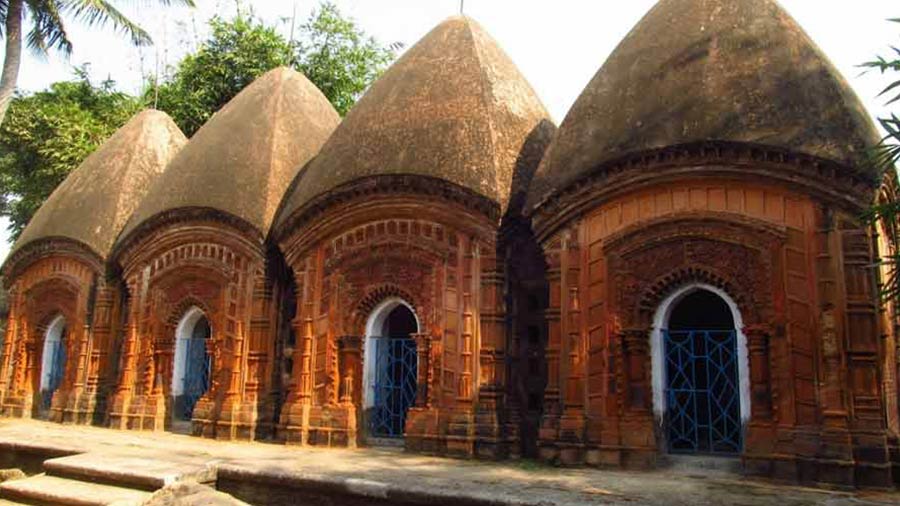

Unlike monumental temples elsewhere in India, terracotta temples are small and intimate

Terracotta temples in Bengal have both local and foreign influences, explains Amit TT archives

You have studied terracotta temples in Bengal in great detail. What makes them special?

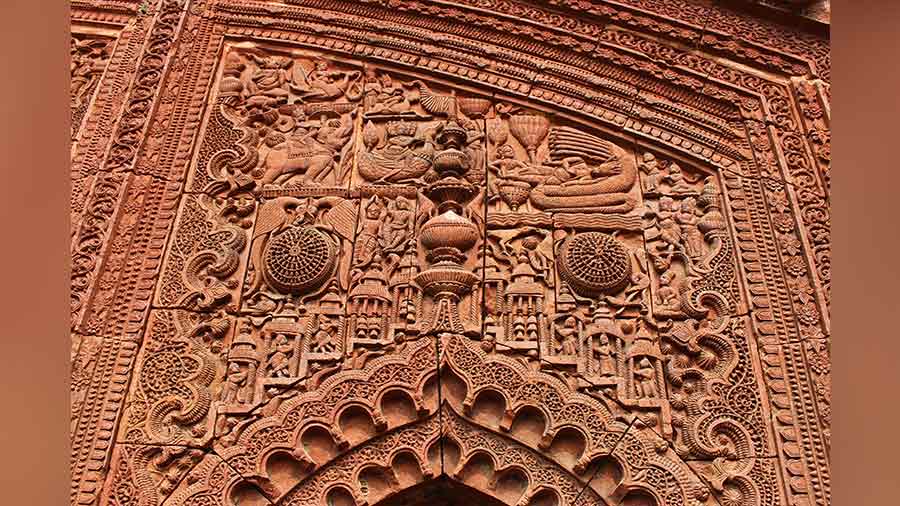

I could fill a few pages on this topic! Firstly, the beauty and intricacy of their terracotta facades and the complexity of their architecture. Secondly, I know of no other architectural tradition in the world that is so syncretic. Terracotta temples combine a range of local and foreign influences. Their arches and internal vaults and domes are Persian (first adopted by the rulers of the Bengal Sultanate in the 15th century); their curved cornices are from the roofs of Bengali village huts; the towers and turrets are based on temples in Odisha; their brick surface decoration derives from Pala Buddhist viharas; and in the 19th century they imbibed European influences such as neo-classical pillars and stucco decoration. Thirdly, I really enjoy exploring and deciphering the variety of figures and scenes depicted on the facades. Unlike monumental temples elsewhere in India, terracotta temples are small and intimate, inviting you to explore the tapestry of stories on the walls.

The biggest threat to terracotta temples today is unscientific renovation

Unscientific renovation has hampered Bengal’s terracotta temples a lot over the last decade, argues Amit TT archives

What have you identified as the biggest threats to protecting and conserving terracotta temples in Bengal?

The biggest threat today is renovation. Over the last 10 years, dozens of terracotta temples that I once saw in good condition have been damaged by unscientific renovation, using cement and modern tiles to “modernise” the temples. In some temples the terracotta panels have been removed, stolen or covered with thick paint that erodes the sculpture. The sutradhars built these temples to last for centuries and they can be preserved simply by removing vegetation once a year and keeping the surface clean from lichen. But many have been neglected for years causing trees to take root and cause structural damage.

Unfortunately, there is very little government or private initiative in Bengal in conserving terracotta temples. I think the temples can only be saved through a large-scale government initiative executed by block-level officers in which villagers are incentivised to take regular care of the structures and reject demands to renovate them. The role of government and conservation organisations should be to provide nominal funds, incentives and deterrents, conservation guidelines, and to educate and promote terracotta tourism. There has been some success along these lines such as with the People’s Initiative in Joypur and the Panskura Purakirti Society.

In 2018, the Bengal Heritage Foundation, UK, raised funds to conserve a terracotta temple in Ghoshpur village in Midnapore. Work was carried out by heritage workers from Burdwan and Kolkata in collaboration with the villagers. I’ve also personally contributed to conservation efforts in Burdwan district (Kendur and Suhari villages). Such initiatives do make a difference, but much more needs to be done given the scale and the urgency of the conservation needed.

The Sridhar temple in Sonamukhi has an unusually complex superstructure with 25 towers in two storeys

The Janaki Ballabh temple in Midnapore Amit Guha

You have travelled to more than 200 villages in Bengal (as well as some in Bangladesh), discovering and studying terracotta temples. Any three lesser-known temples that you would recommend to our readers?

There are so many that are worth visiting that picking three is a difficult task! The greatest terracotta temples are, of course, in Bishnupur but here are three excellent temples in less well-known locations:

- The Janaki Ballabh temple in Tilantapara, Midnapore. This somewhat remote temple is about 40km south-east of Kharagpur, near Pingla. Although built in 1811, it stands out for the extent and quality of rich terracotta sculpture covering three walls and the rich stucco sculpture on the fourth (north) wall.

The Sridhar temple in Bankura Amit Guha

- The Sridhar temple in Sonamukhi, Bankura, about 30km north of Bishnupur. To me this is one of the finest temples in Bengal and is in urgent need of conservation. It’s interesting for two reasons. Firstly, because it has an unusually complex superstructure with 25 towers in two storeys. Secondly, because of the very rich, refined, high-relief terracotta sculpture on all four walls. A visit to Sonamukhi should be combined with the temple-town of Hadal-Narayanpur with its many excellent temples.

The Radha Damodar temple in Suri Amit Guha

- The Radha Damodar temple in Suri, Birbhum, about 40km north of Santiniketan. This 18th Century temple has a facade filled with rich sculpture and very refined and interesting panels. But what’s unusual is that it’s faced not with brick but with a soft, local laterite called phulpathor that is found only on temples in Birbhum, such as in the group of temples at Gonpur.

My upcoming book is aimed at raising awareness about Bengali architecture

Amit with his wife Bidisha and their daughter Vaidehi Amit Guha

What’s next for you in this pursuit of your passion? Most of my free time is taken up in studying and writing about art history. I’ve just completed the manuscript of a book on the terracotta architecture of Bengal (to be published in 2023-24).

The book is aimed at raising awareness about Bengali architecture and the need for conservation, and to help tourists plan visits to see terracotta temples.

I’d definitely like to continue and expand my research in Bengal’s art and architecture. I also feel there’s more to be discovered and re-evaluated about certain periods in the early history of Bengal – the post Pala-Sena Bengal Sultanate and Mughal Bengal – especially in light of Richard Eaton’s book India in the Persianate Age. Perhaps the topic of my second book!

Amit is a key part of organising community and cultural events for BHF across the year in both India and the UK TT archives

You have been a trustee and a member of the management committee at the Bengal Heritage Foundation (BHF) in London for more than a decade. Could you explain how BHF goes about promoting and preserving Bengal’s heritage?

I’ve been part of BHF since the very start of the organisation. We started it with the aim of promoting Bengal and all aspects of its heritage in the UK. We do this through cultural and community events such as Fagun Fest in spring, Rabindra Jayanti, football and cricket tournaments, annual commemoration of Dwarkanath Tagore and our flagship event, the Durga Puja at Ealing Town Hall, one of the largests pujas in Europe. We’ve also helped raise funds for social projects such as Amphan relief work in the Sunderbans and medical help in Kolkata during the pandemic, heritage projects such as the restoration of terracotta temples in Bengal and of Dwarkanath’s tomb in Kensal Green, London, and cultural projects such as the digitisation of Bengali theatre. We’re privileged to have long-standing, formal partnerships with the High Commission of India in London, the Nehru Centre, the British Deputy High Commission in Kolkata, and the British Council. All these organisations actively support our events in London.