Sankar Ranjan Roychoudhury has been around the world, but not in 80 days; bit by bit over 27 years. To date, he has made 30 trips, spanning 125 countries; there were, at last count, 195 in the world.

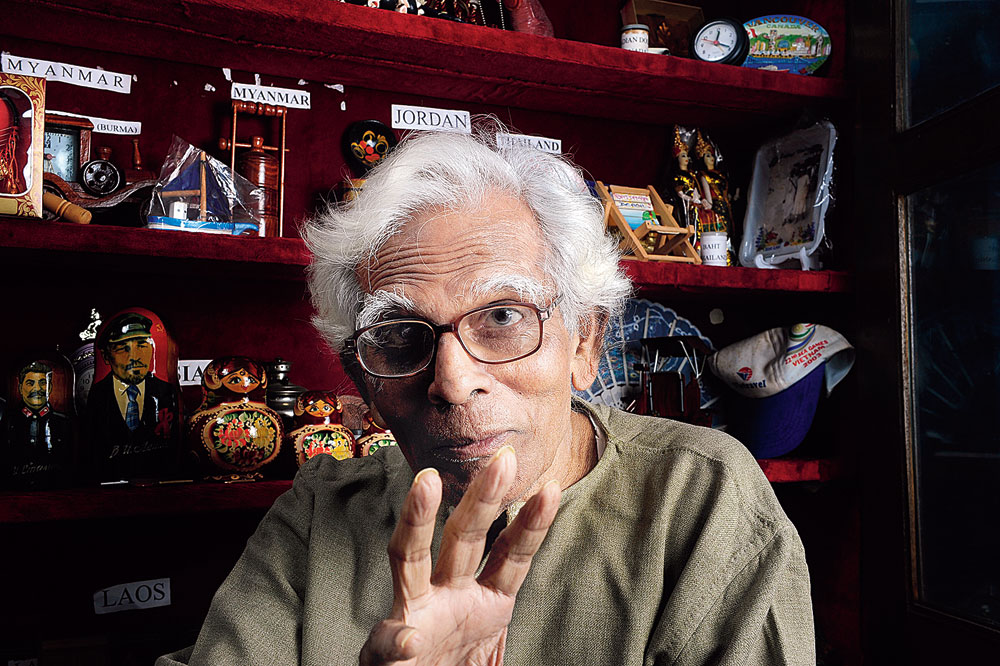

I meet the octogenarian at his residence in southwest Calcutta one afternoon. He shows me his precious possessions — a large world map, framed; four almirahs packed with memorabilia from his different trips. “I call them The Captive World 1, 2, 3 and 4,” says Roychoudhury in a quivering voice, laughing at his own little joke. He is wearing a white kurta and dhoti, and says this was his travel gear throughout his explorations.

Roychoudhury, it seems, was always curious of the great wide world that lay outside India, but he would not have ventured thus had it not been for a friend. “He had just come back from England and he told me I must go out, if for nothing else, only to compare and contrast the condition of India with other countries.”

His memory is razor sharp. He recalls his first trip to Europe in 1989. “I had gone to the travel agent with the intention of travelling to Singapore. That is what my pocket would permit,” he recalls. But post meeting, he was ready for a tour of France, Italy, the Vatican City, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, Netherlands, England and Monte Carlo.

He liquidated his savings, saved each paisa that he could from his earnings and managed to put together the amount required for the trip. He says, “When I returned from the trip, I had decided — this was not going to be my last exploration.”

Three years later, Roychoudhury planned his next trip. This time he decided to eschew a travel agent. He went to the US — San Francisco and Los Angeles on the west coast, Washington, New York and Buffalo on the east coast, and Orlando to the south. Those days the Reserve Bank of India would allow a person to go abroad once every three years. Roychoudhury talks about another peculiarity of those times: “There used to be this Foreign Traveller Scheme under which a person could buy a maximum of $500 for a trip.”

To cut down expenses, Roychoudhury would carry his food wherever he went. He says, “While I had a suitcase and a jhola on my shoulder containing my passport, visa and tickets, I had an additional bag loaded with dry food. It would weigh over 10 kilos. I used to carry sattu, chalbhaja, chire, chirebhaja, badam, badam bhaja, chhola, dalmoot, chanachur, mustard oil, roasted chillies, onions, garlics, sugar and salt. My dinner would be something out of my bag while the lunch would essentially be local cuisine.”

And what did he do about lodging? Says Roychoudhury, “In my years of experience, I have understood that every country has some kind of arrangement for commoners. I would generally look for a youth hostel or a dormitory or what Kiwis call a backpacker and Spaniards, a pension.” He continues, “I would just drop a mail and inform them about my visit. My booking was not accepted but, trust me, each and every time the hotel managers made some arrangement or the other to accommodate me.”

Once, he says, he got an opportunity to spend a few days in the house of an Eskimo. “I was at the North Pole. When I got off at the Kulusuk Airport in Greenland, I found myself standing on a vast sea of ice — there was no tree, no road, no house in sight. I was a bit scared. It was minus five degrees and all that I was wearing was a sweater and a shawl around my neck. Upon enquiry I was told that the cheapest hotel would cost $100 a day, which is what I usually spent over 10 days,” he says. Finally, an Eskimo by the name of Koye took him in for a nominal fee.

Roychoudhury talks animatedly about the long walks, the sledges — “not pulled by dogs, but attached to bikes”, the experience of walking on ice, slipping and falling and slipping again. In the end, Koye took pity and booked him a sledge. Roychoudhury says he was surprised to see a woman driver: “As the sledge lurched up, I grabbed on to the woman. I kept thinking what would happen if I fall and get buried in the snow, and after many, many years scientists find my fossil and do a study on me.”

He also went polar bear hunting that trip. “It was minus 15 degrees outside. Nothing was visible in the white snow but the Eskimos spotted two polar bears and killed them. I was surprised to learn that the meat would be divided among 160 (25 to 30 families) people,” he says. He describes how they cooked the bear meat — boiled and served piping hot without salt even. But this was not the last of his strange food experiences. In South Korea he had fried dog meat, in China he had snake, horsemeat and yak meat, and in Bangkok he ate fried grasshoppers.

The last two years Roychoudhury has stopped travelling. In 2016 he had met with an accident in Africa. He doesn’t elaborate but he has no regrets it seems. He says he has seen a lot and learnt a lot about people and cultures. Some of his experiences abroad, he says, taught him that societies were different and also similar. He talks about bargaining with a cab driver in the middle of the night at the San Francisco Airport. He brings up how some cities abroad are more safe for women than others.

Roychoudhury also shares how Indians are perceived in other countries. “The Chinese would want to click photographs with Enturen or Indians. So would Russians, who refer to us as Indiski. Armenians identify Indians with Amitabh Bachchan, Mithun Chakraborty and Shah Rukh Khan. The people of the West Indies talk of the three Gandhis — Mahatma Gandhi, Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi.”

And now, when he has called it a day, what according to him came most in handy during his sojourns out of India? Says the wise elder, “I learnt Russian, Chinese and Spanish languages. I learnt to be frugal with money and careful with my belongings. But what came in handy unfailingly was my presence of mind and my ability to feel at home wherever I was.”