Commemorating deaths of great men and women is not a regular Bengali social practice. There is, however, one exception; the death of Rabindranath Tagore on August 7, 1941, or what in the Bengali calendar was Baishe Srabon.

Rabindranath complained of several physical ailments ever since he was in his fifties. Some of these affected his health seriously as he grew old. From September 1940 while he was on a trip to Kalimpong, his condition deteriorated and he needed medical intervention. It was detected that he was suffering from complications arising out of an enlarged prostrate. In July 1941, Dr Bidhan Chandra Roy, Dr Lalitmohan Banerjee and Dr Indubhushan Bose — the best surgeons in Calcutta — took the decision that a surgery was necessary to save the poet. Consequently, Rabindranath was taken to his residence in Jorasanko where Dr Lalitmohan Banerjee conducted the surgery on July 30.

It was felt that Rabindranath was near his end. Regular medical bulletins were published in major English and Bengali dailies of the times, and were followed anxiously by the people. Finally, on Baishe Srabon, when news of his passing away — confirmed by the doctors to have occurred at 12.13pm — reached them, a massive crowd of mourners went into a frenzy, almost as if it had suppressed an overwhelming grief while waiting for the moment. Four months later, his son Rathindranath Tagore remembered this eruption of collective mourning as an expression of a collective neurosis: ‘The funeral itself was a most extraordinary and unheard-of experience — millions with fanatical zeal trying to get a glimpse of their beloved one and behaving in a peculiarly irrational manner as though their mental balance had snapped.’

Nirmal Kumari Mahalanobis, the wife of Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, too, remembered the frenzied and transgressive demands of the crowd that had stormed into the Jorasanko mansion to get a last glimpse of the body of their beloved poet. Crowds had broken into the room where family members and a few close associates were bathing and anointing Rabindranath’s body for the last rites. What was clearly an act of violation and amounted to desecration was considered as an expression of sacred respect by the crowd. The tone of grief did not change much even as people followed the hearse, especially decorated by the artist Nandalal Bose of Kala Bhavana, that carried the body in a procession through the city to the Neemtala crematorium.

Tagore’s funeral procession TT archives

In the intervening eight decades, Baishe Srabon has ceased to be a mere date in the Bengali calendar for the educated middle-class Bengali. It has become a metonym for collective mourning, an occasion for a catharsis that was initiated with the death of Rabindranath, the man who has shaped much of their social and cultural identity — in life as much as in death.

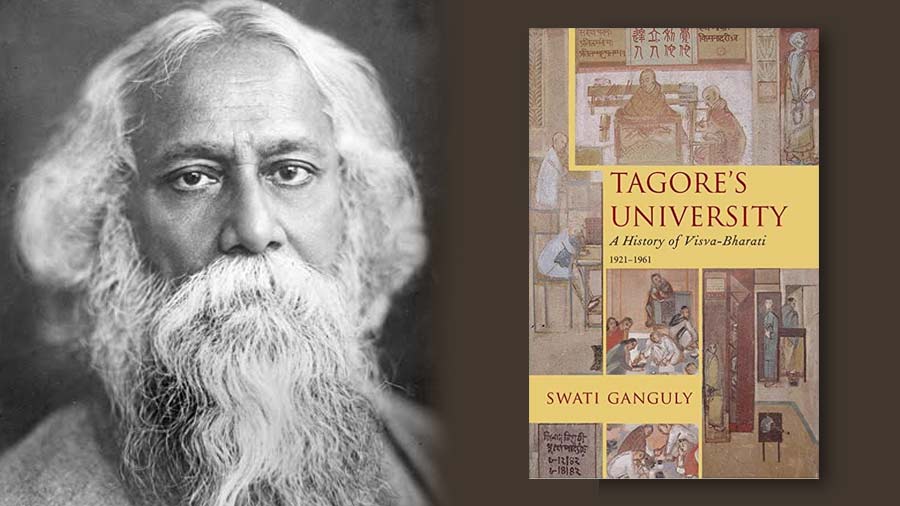

The excerpt below is from Tagore’s University: A History of the Visva-Bharti (1921-1961)

********************

Absence, anxiety, apprehension

On the morning of 21 September 1941, a congregation had gathered in the Chhatimtala, a grove of chhatim trees. The chhatim’s leaves were (and continue to be) of great symbolic value in Visva-Bharati’s annual convocation. It was customary for ceremonies, especially those which marked the more formal and solemn events in the calendar of Visva-Bharati, to be held at Chhatimtala, given its association with the sacred. A small white marble prayer seat located there had a plaque bearing an inscription in Bengali which, translated, read: “He is the comfort of my heart, the joy of my mind and the peace of my soul.”

Chhatimtala at Santiniketan

This was where the memorial service for Rabindranath Tagore was conducted on 17 August 1941, ten days after his passing, with the chanting of Vedic hymns and verses from the Rigveda. Vidhusekhar Bhattacharya – who had formally resigned but whose links with the institution had never snapped – and Kshitimohan Sen performed the rites. During this occasion Kshitimohan appeared aloof, wrapped in thought as his eyes swept over the congregation in the Chhatimtala. A special meeting of the Parishat was soon convened to pay homage to Rabindranath Tagore and discuss the ways in which the institution and community would come to terms with the loss. Charuchandra Dutt, Upacharya of Visva-Bharati, articulated the sense of an absence:

We, workers of the Visva-Bharati were till now safe in the protective shadow of a mountain. He guarded us from all buffetings of misfortune in order to enable us to do our own bit of work unhampered. Now that he is no more we will have to resist the full force of the storms that may come in future days . . . individually, to uphold the greatness of this institution which he has done so much to foster. It is true, the brunt of the work falls on the executive, but why not let us assure them that we are prepared to share their work at this critical juncture.

As Kshitimohan listened to Charuchandra, it struck him afresh how difficult the path ahead was likely to be. Revered as the kulasthabir (community senior), Kshitimohan was known as an observant man who contemplated matters deeply before reaching a decision. He had gradually become an invaluable member of many administrative and academic committees and was responsible for the running of Vidya Bhavana. He recalled how a pall of gloom had enveloped the ashram since the twenty-second day of Sravana, the day when Gurudev breathed his last. Though the academic and other activities of the institution had continued as usual subsequently, the spirit of the ashram would never be the same again.

Now, more than a month after the poet’s death, the dark shadow of collective grief and mourning seemed to be fading – if ever so slightly. Perhaps this was linked to the change in seasons; the monsoons were coming to an end and the leaves on the trees – mango, sal, mahua, jacaranda, and others planted over decades in the ashram premises – had a luxuriant green hue. Sarat, early autumn, a bewitching and evanescent season in the region, had begun. The days were still hot but the mornings and evenings were pleasantly cool.

Rabindranath had been an indefatigable writer of epistles, communicating with friends and family from every corner of the globe and different places within the country. In some of his letters he explicated his initial ideas when setting up the Brahmacharyashram and later Visva-Bharati. Sometimes he laid down guidelines for the functioning of its various institutes and gave suggestions on the curriculum of studies in languages and culture, especially for the research programme of Vidya Bhavana. He provided elaborations on the relevance of Visva-Bharati in turbulent social and political times; he wrote movingly, in prose studded with metaphors, of how he had conceived of Visva-Bharati as a counter to the forces which seemed to him bent on destroying humanity. Now there would be no letters home, no homecoming for the man who was like an unfettered bird, flying frequently out into the deep blue and returning to his nest.

Excerpted with permission from Tagore's University: A History of Visva-Bharati 1921- 1961 by Swati Ganguly published by Permanent Black in collaboration with the New India Foundation and Ashoka University. Swati Ganguly is a professor at Visva-Bharati.