Guitarist Amyt Datta has a story to tell. It’s about this plant that is red in colour and beautiful to look at. But it is very angry with us. Why? The virtuoso player and composer offers an answer in his latest album. Red Plant is a summing of sorts about the time we live in. The lockdown meant Calcutta was “quieter”, he says, thereby amplifying his own “internal sounds”. Hence the recording. The emotions are raw. There’s love and despair. The feelings are deep. There’s excitement and depression.

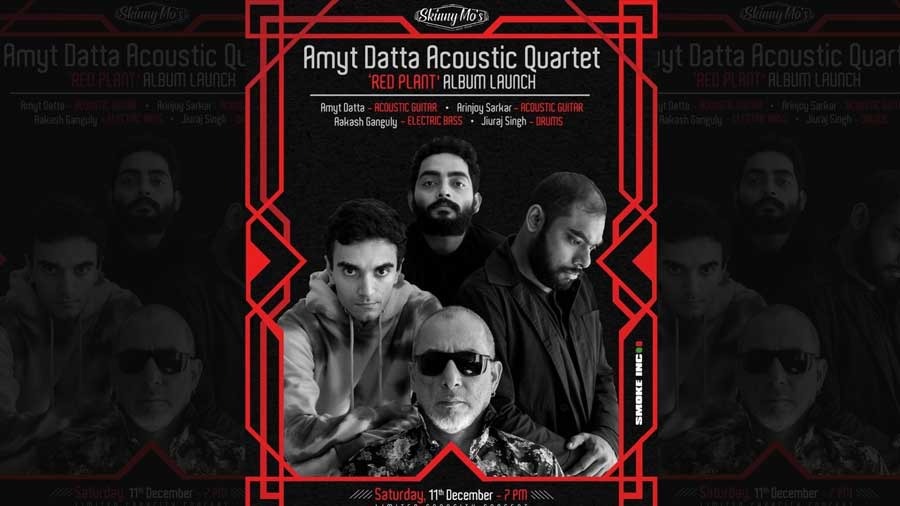

Never one to really talk about his music, Amyt, however, decides to open up about the “process” to The Telegraph My Kolkata as a precursor to a concert he is scheduled to present at Skinny Mo’s on Saturday, December 11 when he will join band members Arinjoy Sarkar, Aakash Ganguly and Jivraj ‘Jiver’ Singh to play his music, new and old. He explains, perhaps for the first time to a listener, his four-hour warm-up exercises on the fretboard, the challenges the guitar still offers, joys and heartbreaks that those six strings still inflict on him, and what exactly did Miles Davis mean when he said playing jazz standards is boring. Excerpts.

Congratulations on what is an absolutely delightful album.

Thank you so much.

I found the album to be something like a statement from someone who is taking stock, staying put for a while to soak in the ambience, letting his thoughts collate into something wholesome, and then, maybe, moving on ahead again.

Like you said, this album is a collection of life’s experiences in general. And because we are musicians we are expressing that through the medium. I’ve been working on these ideas for almost three years. You know, toying with the seed of an idea, a riff, or very often just a title. Over the last one-and-a-half or two years, we have all been kind of locked up at home. And it’s not that I did something different from what I usually do. I am usually anyway locked up at home either practising, writing or teaching. But most of my time I am practising at home on my own. So, I did the same thing. But because, in a way, the town was quieter I got inspired to record. When external sounds reduce, you tend to hear your internal sounds better.

Yes, your thoughts seem clearer.

Yeah, then I got inspired to finish the recording.

You have often said that dissonance is a major feature of your music. Where do you see Red Plant in the context of your earlier albums, Amino Acid, Pietra Dura, Ambiance De Danse?

If you only think of dissonance, Amino Acid had more direct dissonance. The approach for that album was different. It was electric and we went for sounds as in ‘noise’ also. I thought of that as ‘music’ too as it is a wrong notion that noise is not part of music. At least that’s what I think. But this one, being an acoustic album, I wanted it to be a little bit more organic, but harmonically dissonant. Pietra Dura is not that dissonant. But if I go technical, the chords are voiced in a not-so-sweet way. Even though the first layer of it is kind of nice and soothing, because it’s acoustic music and it is slow and nothing else is playing. But if you have to present the tracks as a player, then you’ve got to study them and get the exact sound of the piano. Likewise, Red Plant is dissonant harmonically, not noise-wise. This one is more within the territory of music convention.

I found the album very melodic and harmonic. Take us through some of the tracks. I mean, the inspirations, titles… And the idea behind the title track, Red Plant.

Let me try and remember how I got inspired. I think the seed of the idea came from a very technical source. In the western way of thinking it's like a mode called Mixolydian, but with an alteration. You take the second note and you flatten it. And that currently matches with a raga in the Indian way. One of the ragas. I know the name, but I don't want to say it as I'm not an Indian raga specialist. So, that kind of inspired me. It was like western, but with a little bit of an Indian sentiment hidden in it. And I think I took the sixth mode of it. It's like you take a scale and make a variation. Like I said a flat two, and then the same string of notes, but you start from another root. So the way the notes come, the distance of each note changes and, therefore, the sonic vibe changes. So technically speaking, that was my source of thought. Then, as I was noodling around with the sound and the vibe, and I got some chords, and it started to take birth as a piece of music. The way the tune came about, it became a bit aggressive. So that anger, the red symbolises that. But also it had a very organic feel — at least some parts of it. So it was like green. Organic. Nature. Plant.

Life?

Yeah life. So, exactly like how we are. So when it finished, I said Red Plant is a great name because you can look at the plant and see that it’s a beautiful plant. Red and beautiful. But it's red also because it's annoyed and angry with humans. Plant is nature and nature is angry — ‘look what you humans have done to me’.

Right. The second track, Transoxiana, is one that you have played often at live gigs. That's a very exciting track.

It is. I don't know, Shantanu, why. But maybe you have the ear to feel the excitement even without language (words/lyrics). I'm not singing, it's instrumental music. But in spite of that you are getting the feel. And that’s the instrumental language that we try and put across. It’s a little bit difficult than a vocal tune. Still, at least you got it. Again, it’s got this pa ra-ra feel to the melody, the kind everyone on the streets hum. The (overall) sense of it is triumphant, a feeling of having conquered. Transoxiana is a region around Greece that Alexander kept on invading. So a conquering and triumphant feeling is what I'm trying to project. And Transoxiana is a beautiful sounding word.

Yes it is. I had to look it up though. Now, about Yusra, a track I warmed up to immediately. The moment I heard it, I was transported to Jerusalem. I was reminded of my trip there. I don’t know why though. I think the atmosphere, it was dusk, some people were praying at the Wailing Wall and a piece of music came wafting through the air from among the many shops that are there in the walled city.

Oh! Tell me what aspect of the piece took you to Israel and not anywhere else.

I would think the sound of the guitar and may be some of the phrases in the tune. Because I remember ending up going to the shop where that piece of music was playing and buying the CD. Jewish Guitar is the title of the CD which has like three or four people just playing acoustic guitar.

This is what I mean… As a (guitar) player, I have learnt the craft to express what you've just felt. You're receiving without knowing the language, and you’re understanding it. That’s the romance of any art form in a deeper form. And why Yusra? That is the name of this girl who swam across, I think from Libya to flee civil war. She took her sister with her and swam across to Greece after her boat capsized… She is a survivor. She now holds a UN post. In fact, I named the track Sister Yusra. And then my niece said just Yusra would do. So I left it at that.

Describe the piece for us.

If you listen to the tune, it’s got movements. It starts very slow. The slow part signifies how this young girl was born into the sadness of war, bombs, poverty and struggle. You can die every day. So what is life teaching you or telling you? That’s the sad part. At that age you can’t think much. When you should be playing, you are protecting yourself from bombs and bullets. I mean come on. It has some of these brooding chords… then the piece gets into the upheaval because she went through this journey of fleeing, leaving her parents back. And again, the track slows down. It’s like the waves in the sea. Life is exactly that.

Towards the end of the track, the guitar wakes up even more. There is a kind of an emphatic statement.

Correct.

Which immediately feels like, ‘oh my God, is it something different? Is it a new track?’ But then, you realise that it’s part of it.

That's how I tried to write the surprise element, because you wake up, you're born and you're surprised with bullets and bombs. And that’s also decided by some other people in some other country, God knows who.

One of the general conventions of jazz — I know you are not one to stick to conventions — is to introduce the main theme and then various instruments take turns expanding on it only to come back to the original tune. In a lot of the tracks in Red Plant this doesn’t happen. You don't end the way you started.

It is a kind of evolution. Once, Miles (Davis) said that playing standards was boring, which obviously it is not. What he meant was that you need to change. Meaning, you play the head and then you improvise over the chorus — saxophone, piano, bass, drums, or whatever. And then you play the head out again and then end the song. Almost every tune is like that. But then with time, you challenge that process. Put it on the shelf and proceed. Not that you reject it, you keep it as a treasure. So when I try and write a tune, I go more with my feeling than stay within the conventions of the formulae that music has taught us through books.

At the same time, you wouldn't stop yourself from doing it if you felt a tune deserved to end the way it started?

Of course I’m open to that completely. But it has to dictate its own terms within the movement that it’s going through.

This is very complex and it's all happening in your mind. So, when you are done with the composition, how do you take this to your band, in this case youngsters, some of whom are your students.

Well, Arinjoy (Sarkar) the guitar player is the only student. Bass player Aakash (Ganguly) hasn’t been a student of mine in the formal sense. And there’s Jivraj-‘Jiver’-Singh. Once I feel the pieces are kind of complete, then I take it to the band, usually the bass player and the guitar player. I have a couple of sessions with them and they pick up the parts. And both of them are very mature. Arinjoy plays classical guitar also. He has this piano-like classical approach. He understands the sentiments. So that’s why I asked him to play. People know him as a blues player — of course he’s a great blues player — but he also has this background of orchestration, sentiments and poetry. If I say ‘why don’t you behave like a piano player’, he’ll know exactly what I mean. Same with the bass player, Aakash. He is completely on his own. He hasn't trained under any teacher, plays from experience. He’s just talented. He’s physically also very good (with the instrument). Some of the passages we play, they’re not very easy to play on the bass guitar. But he gets it. So when all three of us are kind of ready, then we sometimes play the tunes at a gig. This is a new band as Jiver is joining this acoustic set for the first time. And with Jiver, I have this complete trust of just giving him this recorded stuff with the click (time signatures).

And he, sort of knows your mind.

Exactly. You said it. Somehow, he kind of knows the inside of my mind. When we talk about what we want in the music or discuss the kind of approach to take we hardly speak music. We talk about some scene or some descriptive visual idea, like dark, cloudy or bright, and he gets it bang on. And technically, he never recorded with us when we were recording. He's doing it separately. But when you are listening, it sounds like we are playing together. My trust towards him is absolutely a hundred per cent. And he can also tell me — he hasn’t yet — that this ‘is ‘not my cup of tea’ and ‘I'm not going to do it’. Because he understands himself fully.

So there is no problem if there are situations where he plays something and you don't like it? You tell him?

Yes, absolutely. He’s a musician, he’s not only a drummer. In fact, sometimes I think he knows my music better than I do.

You have been playing the guitar now for close to 50 years.

In 2023, it will be 50 years.

Right. So how does the guitar still challenge you?

Everyday. I mean there's no escape. Because it puts you down every time… Like any art form, especially the guitar, in the beginning, it's kind of bright because it's easy to play a few chords and you can play many songs. But it also tempts you if you go deeper, and makes you think it’s almost close to piano. And you can do a lot of pianistic stuff on the guitar. It's a little bit physically challenging, but it's very close to piano in a way. But then it takes you to that zone as if saying, ‘come with me, I'm almost like a piano’. And then it challenges you and drops you like a piece of brick. ‘Work it out and come back to me,’ it seems to say. The guitar is a really weird instrument. It gets so difficult. And it's so confusing. That 12-fret fingerboard, I keep saying, it’s more complex than Amazon. …eventually it is a difficult instrument.

That coming from Amyt Datta.

(Laughs) And you know what? It is more difficult because it sits on your lap and touches your chest. It tells you: To get me you have to bleed.

You told me once that you need to practice for four hours a day and then feel like ‘competent’ in your own mind to may be go and record.

Yeah. Roughly it takes about four hours for me to get gig ready.

So what do you do in those four hours? Is there a set pattern of exercises?

Yes. It is quite boring in the beginning. The first maybe half an hour or one hour is to come to a neutral point. Because when you sleep and wake up, you're physically also a little bit under. So you have to bring it up to the level of normalcy, like ‘zero’. Then you have to hot up to get gig ready. Also keep in mind that sometimes with excitement (of performance) or for some reason, the speed at which you rehearsed (a track) has gone up on stage. So you have to deliver. Suppose a song is at, say, 140 BPM (beats per minute), I will try and practice it at around 146 BMP. So I’m kind of ready. But all this is in theory. I may have played four hours before the gig, but at the gig I might just blank out.

Does that happen?

Yes. Especially this kind of music, because this is not the music that you can just mug up. You have to manufacture at the moment, on stage. So it's kind of challenging, both physically and to come up with ideas, harmonically and rhythmically, to navigate over the harmonic shifts … not just being correct, but better than correct and create a little bit poetry if possible. The funny thing is that that’s my genetic wiring. I like to write (music) and then find that I can't even play it. And then I practice to play it. So very often I write without the instrument. When you have the instrument, you stretch till you can play. But if you write it, you're writing as if another guy is writing to give it to a player to play. The player, by the way, is me. Then you have nothing to do. You have to play it.

So, you are setting a benchmark for yourself all the time?

Or trying to at least.

While writing, do you realise that it’s going to be tough?

Sure. Very often it happens that I practised a four-bar passage for the whole afternoon and then in the evening, it’s still not really doing that well. But it gets better.

In this age of YouTube stars, what would you like to tell serious young musicians of today?

This is a funny thing. When you say I ‘love’ doing this, or I ‘like’ doing this, you can control it. If you see the future's not there, or it's dark, you can (decide) not do it. You can like it all your life, but not do it. But passion doesn't give you that choice, whether there's a deep hole or a volcano that you might fall into, you just carry on because that's your passion. It doesn't give you that choice. It's so deep that love, so profound that it's almost ruthlessly kills you. And you kind of like being killed — in the sense, it's like passion is hugging me, but (it’s) too tight and I got breathless and I died in its arms. So, a good, honest musician has much more to think and say. He or she has in his/her life a lot more than what people see.

So, what would be your advice? What do you tell them?

Listen to your calling very closely. Can you take the challenge? Let me tell you something. I've taught over many years and not everybody played great. But some of them dropped out. Because they couldn’t handle it. And they did this and that, and the excuse was ‘I had to run my life’ by doing whatever kind of music they wanted to do. I don't even know sometimes whether that’s music at all. But now, a few of them call to ask, ‘Sir, what can I play over this and that’, all technical stuff. So, I tell them, ‘is your student asking you this?’ He says, ‘Yeah, yeah’. I say, ‘I taught you all this 10 years back. Why didn't you learn it then? You betrayed it then, now you are using the same thing to earn a living. If music could speak or abuse, then it would have done so to you all in a very filthy way.

You have devoted your life to music. Would you have been happier if more and more people heard your music every day? Or have you come to terms with the fact that not everybody on the street is going to pick it up.

First, do I want more people to hear this music? Yeah, sure. In whatever way music is consumed these days, I wish people hear this kind of music — not only my music. But coming back and telling me how great it was? No, I really don't bother. Frankly, I don’t really care about that. A normal listener who comes and appreciates me would never know the degree of work behind it. I don’t expect them to understand. Generally, I don't really think about it.

What do you tell yourself?

Actually nothing. Because I have been shaped like that. I never shaped myself. But the situation has shaped me like that. So I just carry on doing what I do. I think the rest answers itself. The moment you ask, ‘Why should I carry on? What for?' then this material world will enter your head. Then, because the way the world is, you will stop doing it. I will still keep trying to learn this instrument called guitar and I will try and write different kinds of music.

So, what’s next?

I have already written a few tunes for this electric album which will be a trio set-up — bass, drums and guitar. I’m trying to go slightly retro, but in the language that I've been writing (music) now. It’s ready. I have to just kind of play, especially with Jiver, and open up the arrangements and see where it goes.

You had told me about a project wherein you were planning to use a special tuning of the guitar.

This is the one. It’s electric.

The guitar will be tuned differently? Explain that.

The guitar is conventionally tuned, but the octaves are flipped. Meaning, where you are supposed to be having a low E, I have a high E there. So, I figured out about seven or eight different types of tuning like that and thought this was the best one that works. And it only uses two sets of strings. Otherwise, I would need three sets of strings.

Well, that's sure to be another experience. It was a pleasure talking to you, Amyt da. Congratulations once again for a wonderful album.

Thank you.