Amit Kumar Bansal’s Tollygunge home has a timeless quality to it. Bansal, 67, preserves memory in objects. His rusty cameras and elaborate toy trains all tell a story.

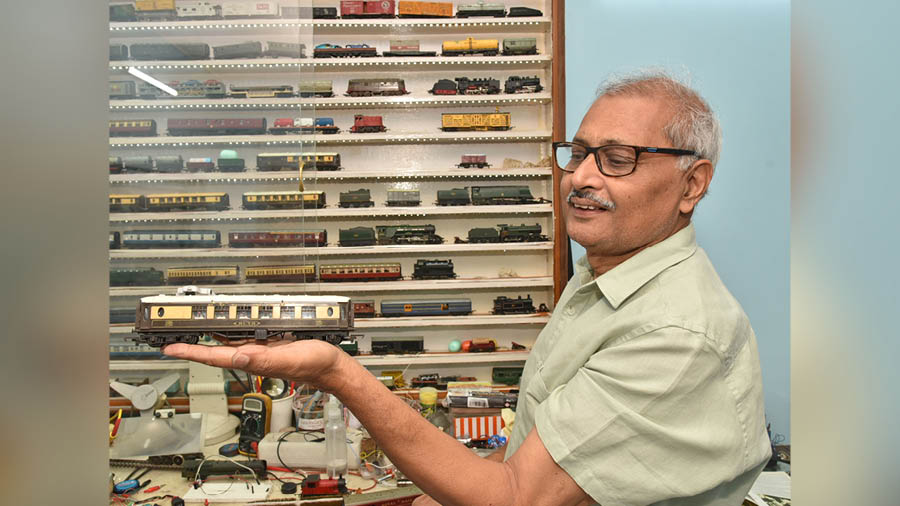

Born in Kolkata in 1956, Bansal travelled in Darjeeling’s toy train as a child. His love for trains felt instant. As an eight-year-old, Bansal saw in the shop window of G. K. Sports a beautiful toy train layout. “I wanted to buy it, but they refused to sell. The layout was only meant for display. I came home and threw a tantrum. That’s when my father got me my first toy train set from India’s Hobby Centre. I didn’t stop at one. We kept buying more.” Showing off his first train, a perfectly preserved key-operated Hornby toy, Bansal remembers more of his childhood train journeys. “When we would take the Udyan Abha Toofan Express to Agra, we’d travel first class. I remember us chilling the compartment with a Rs 25 ice box.”

Growing up, there were only three shops in Kolkata where Bansal could buy toy trains: G.K. Sports, India’s Hobby Centre and Wonderland. “Whenever someone went on a foreign trip, they would bring trains for me. In those days, electric trains were very expensive, so I made do with analogue." An avid collector since he was child, Bansal started to make his own track layouts in his adolescence. He kept his first one under his bed. Bansal’s wife, Nandini, remembers a time when his train equipment would always be strewn across their room. “When I asked him when it would all get done, he said, ‘In five years.’ Fortunately, for us, the pandemic came around,” she smiles.

Bansal with his first toy train, which he purchased from India’s Hobby Centre

During the Covid lockdown, Bansal emptied out a room in his house and began to assemble an elaborate toy train layout there. “I devoted an entire year only to this. From 8.30am to 5.30pm, I would be in my hobby room, perfecting everything.” Bansal’s daughter, Shreya, says, “We joke that the lockdown was difficult for everyone except Papa. He gave all his time to trains.” She adds with a laugh, “My mother wasn’t very happy about this, though.”

Training his sights

The layout in Bansal’s hobby room is intricately detailed. Everything you see — right from the greenery and the mountains to the homes and traffic signals — looks elaborate. Shreya tells My Kolkata, “My grandmother was diabetic, and so we would stock up on insulin. After she passed away, my father used her spare syringes to make traffic lights.” Making the case that her father had mastered resin art long before it arrived in India, Shreya lists several everyday items Bansal had used to make his tracks: charcoal dust, Scotch-Brite, even termite-infested wood: “Nothing in this house is ever thrown away. My father finds a way to use it all here.”

Bansal has an entire room dedicated to his toy train set that he calls his happy place. ‘I have made everything in this room with my own hands’

To make his layout realistic, for the tracks to switch and the lights to flicker, Bansal found that he needed tools that were only available abroad. Not one to refuse a challenge, he eventually decided to make these himself. He built a speed controller to regulate how fast his trains would move. He used static electricity to ensure that the grass he made from jute and fennel would stand straight. Last year, he also made a wheel cleaner. “Back when I started, YouTube wasn’t a thing. I learnt all this through trial and error.” Shreya calls Bansal “an unpaid mechanic”. She says, “He can do everything. He can even repair a CFL bulb.”

Bansal has a workstation to repair the toy trains’ damaged parts

During a test run, one of Bansal’s trains derails. Bansal is unperturbed. Confident that he has the tools and expertise for any kind of repair, he says with a chuckle, “Derailment is inevitable. Aap Indian Railways ko hi dekh lijiye! (Just look at the Indian Railways!)” Though there is a grandeur to some of his trains — one can deliver post, while another lets out smoke — Bansal says he is still drawn to simple things. “Even today, I prefer travelling by train. I take the train wherever I go, be it Darjeeling, Maglev in China or the Swiss Alps.”

A control panel for the entire setup

Bansal’s family has taken to giving him train-themed gifts. Shreya once went all the way to Madurai to buy him an engine. “We also got him one of the mini-houses from Australia. All of us enjoy coming here, especially my daughter. Each time, he has done something new. I just noticed his coaches now have lights!” Bansal adds that if he could have his way, he would make a track ten times bigger. “Maybe I will make an outdoor track someday.”

Bringing into focus

Bansal has a collection of over 40 cameras and record players, all in perfect condition, some after over 60 years

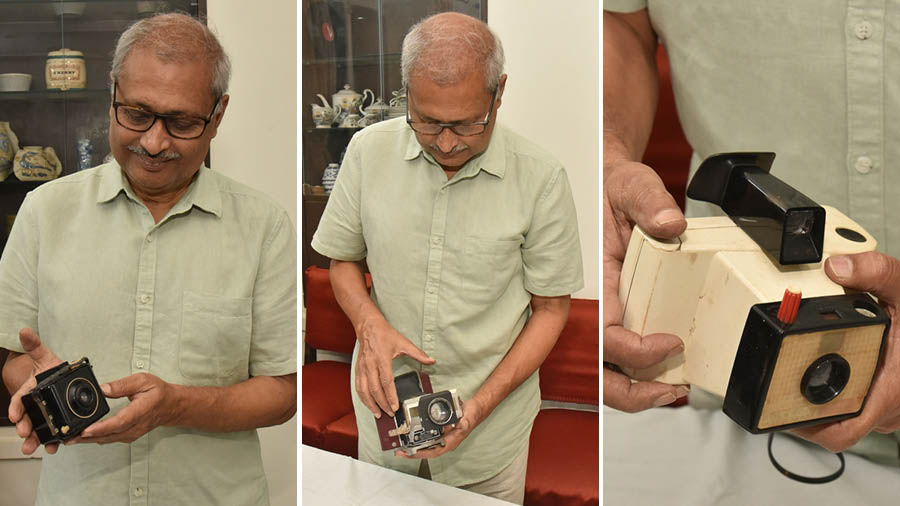

Trains aren’t Bansal’s only passion. He has also inherited from his father a love for photography. Showing us his first camera, a Baby Brownie, Bansal says, “It could take both black-and-white and colour pictures. I bought it from my pocket money for Rs 200 when I was 12.” Shreya remembers how her father would bring his cameras and camcorders to all their holidays. “When the Bansals went for a family picnic to Diamond Harbour or Joka, Papa was always the designated photographer and we were his muse.” Bansal adds that he would earlier have to ration his pictures. “But over the course of one US trip in 1998, we used 42 reels,” he smiles. Shreya complains about the ridiculous poses her father would demand. “We have hundreds of pictures of us just holding the pillars of Pashupatinath Temple in Nepal. Our home has VCR cassettes of every holiday and almirahs full of albums!”

Unlike his father who kept his cameras locked away, Bansal encouraged his children to play with his. He gifted Shreya her first camera when she was 15, and over time, his youngest daughter, Manini, began using photography in her design work. Bansal, sadly, lost some of his enthusiasm for photography with the advent of digital technology. “With the phone, you just have to click. There is no need for any kind of setup. That used to be half the fun,” he says.

(Left) Bansal with the first camera he bought; (centre) the oldest camera his father left him; and (right) the first polaroid to ever be sold

In Bansal’s collection of 40-odd cameras, the older ones use a glass-plate mechanism. He even owns a variant of the world’s first polaroid camera. “I regularly get them serviced from Latif Precision Works in Dharmatala. The serviceman’s father used to maintain my father’s cameras, so it all feels poetic. I don’t much use my cameras anymore, but I proudly display my collection at home.” Much like his trains, Bansal’s cameras, too, are a treat for the eyes.