Imagine you are living in Canada, some 7000 miles away from home. You wake up one morning to find your community being insulted live on Indian television. What would be your first response?

For Karanbir Singh Sekhon, there was only ever going to be one answer: “I knew I had to fly back to India immediately. And that’s what I did.”

Karanbir, an IT and audit professional based in Canada, had been devastated by how sections of the Indian media were portraying his fellow Sikhs in light of the farmers’ protests raging across parts of India towards the end of 2020. Coming from a family of farmers and soldiers, he could not believe how blithely his community was being cast in the role of anti-nationals.

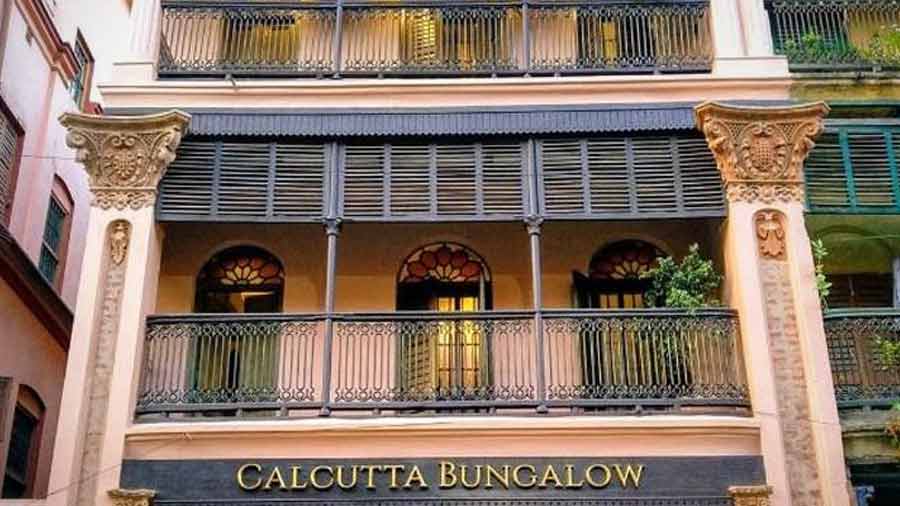

On a brief sojourn to Kolkata, where Karanbir put up at Shyambazar’s Calcutta Bungalow, the 31-year-old activist and community builder spoke to My Kolkata about how the passage of the three farm acts by the Government of India in September 2020 and the subsequent protests that ensued transformed his life.

Bengal… the intellectual and revolutionary nerve centre of the country

Karanbir stayed at Shyambazar’s Calcutta Bungalow during his two-day trip to the City of Joy Courtesy: Calcutta Bungalow

“The farmers’ protests gave me new meaning and purpose along with a desire to look for like-minded people who can help revive the democratic spirit of India,” says Karanbir, at ease in the courtyard of Calcutta Bungalow, where his voice assumes a resonant quality. His two-day trip to Kolkata, during which “I could only see five per cent of the city”, was meant primarily to connect with such like-minded individuals. “Bengal has always been the capital of ideas, the intellectual and revolutionary nerve centre of the country. And as a Punjabi, I know how much Punjab and Bengal have suffered. Ours are the two states that faced the worst consequences of the Freedom struggle as well as of Partition. This is why I wanted to come to Bengal and speak to people and see if they can identify with my cause.”

What exactly is Karanbir’s cause?

“It’s to create small ripples that can lead to genuine change in our country. The kind of change that takes us closer to being the nation that our Constitution sets us out to be.”

Born and raised in Patiala, Karanbir moved to the United States at 21 to complete his Master’s degree from the University of Florida. “That’s when I first got a taste of politics through my work as a student leader. Be it campaigning, narrative building or solving local issues, I was at the forefront of the student’s movement in Florida,” describes Karanbir, who shifted to Canada for professional opportunities following the completion of his education.

A democracy of, for and by corporations

With his specialisation in auditing and cybersecurity, Karanbir spent several years hobnobbing with corporations, the sort of people “that only care about the bottomline, about making more and more money.” Meanwhile, back home, “India was becoming a country for the oligarchs, a democracy of, for and by a few handpicked corporations who were controlling everything.”

Then, in the autumn of 2020, came the farm bills, or as Karanbir calls them “the anti-national bills that didn’t believe in equality of opportunity or dignity of labour.” According to Karanbir, the bills had nothing in them for the farmers, who would be left at the mercy of corporations if the bills had stayed on as laws.

“Through the farm bills, the Indian government was creating a playground so that a few people could play with India. The bills would dictate how and what India eats, there was no way they would’ve improved the lives of the farmers. In fact, without the provision for a minimum support price (MSP), they would’ve made most of the farmers poorer,” explains Karanbir.

My goal was to travel as widely as possible and mobilise

Karanbir travelled across India during the farmers’ protests, from Delhi to Pune, from Uttar Pradesh to Karnataka TT Archives

After the Indian media’s depiction of farmers as terrorists anguished him to no end, Karanbir landed in Delhi in early December of 2020 and went straight to the Singhu border. “Once I came back to India, I had a simple task – get as many numbers as possible in the border areas. My goal was not to sit in one place and become a star, but to travel as widely as possible and mobilise…. We wanted to magnify our collective voice to prevent the government from snatching away the legitimate rights of farmers.”

Meanwhile, the protests were on the boil back in the US, so Karanbir decided to fly back. He spent 54 days in Washington D.C., living out of his car and speaking to as many people as possible. On an average day in the first quarter of 2021, Karanbir would be present at around six to seven gurudwaras in America, spreading his message of peaceful protest. “I covered the entire stretch between Massachusetts and South Carolina (over 900 miles) and spoke to tons of people,” says Karanbir.

The problems of the farmers are still there

So what does Karanbir make of the repealing of the three controversial bills in November 2021?

“The repeal of the bills isn’t a victory for the farmers. Yes, in some ways, it’s a victory for Indian democracy, because protests can still have some effect. But when you look at the broader picture, the problems of the farmers are still there. MSP is only guaranteed for 22 crops, whereas farmers around India grow more than 600. Farmer suicides aren’t reducing. Many of those arrested during the protests are still in jail, their tractors and other possessions still seized by the State.”

What now, then?

Before answering, Karanbir asks for a couple of glasses of water. A brief thought of shifting to the Calcutta Bungalow terrace – a prime attraction of this beautifully restored old North Calcutta address – pops up in his mind, but he dismisses it promptly. We continue in the courtyard.

“Samvidhan, Satyagraha, Sangathan,” says Karanbir as a response to what can be done now, before elaborating, “We need to amplify the rights and powers provided to us by the Constitution of India. We need to struggle based on our quest for truth and justice. And, above all, we need to involve a diverse group of people from different castes, creeds and communities to have our goals met.”

Vital role of women and of young entrepreneurs in farming

Karanbir also adds two two important caveats. The first concerns giving due prominence to the role of women in farming. “We don’t realise how much effort women put in to make farming possible on a day-to-day basis. From sowing seeds to tilling the land to rearing the cattle, women work just as hard as the men, if not more. So they need their share of visibility and voice whenever we’re talking about farming.”

Karanbir feels that women’s role in farming has to be acknowledged in India TT Archives

The second is the incorporation of entrepreneurs into the farming sector. “A few years ago, India seemed to have decided to incubate and optimise start-ups. But where are they today? How many homegrown start-ups have gone on to become sustainable? We need fresh entrepreneurial ideas that can last the course, and we need these ideas in farming, too. Young girls and boys need to be taught how to make farming more marketable and incentivise others to join the sector.”

Democracy at its core is still about independence of thought and action

Where does Karanbir see himself as part of the farmers’ movement going forward?

“I see myself as someone who’ll continue to ask questions of the government and call them out on their mistakes. I’m not, and never will be, part of a political party. My role is that of an active citizen who wants farmers to have a better life.”

Shuttling between North America and India for the time being, Karanbir wants to expand the network of people “who care and want to change things, who still believe that democracy at its core is about independence of thought and action.”

Karanbir does not see himself as being part of any political party Courtesy: Karanbir Singh Sekhon

Nationalism, as Rabindranath Tagore memorably said, can’t supersede humanity

Seated a seven-minute drive from Jorasanko Thakurbari, the invocation of the Bard of Bengal seems almost inevitable. The context? The thin red line of patriotism. “For me, a true patriot is someone who’s willing to criticise their government to protect their nation. Patriotism, or even nationalism, as Rabindranath Tagore memorably said, can’t supersede humanity. That’s something we’ve got to remember, or else we’ll be going down a treacherous path very soon,” concludes Karanbir.