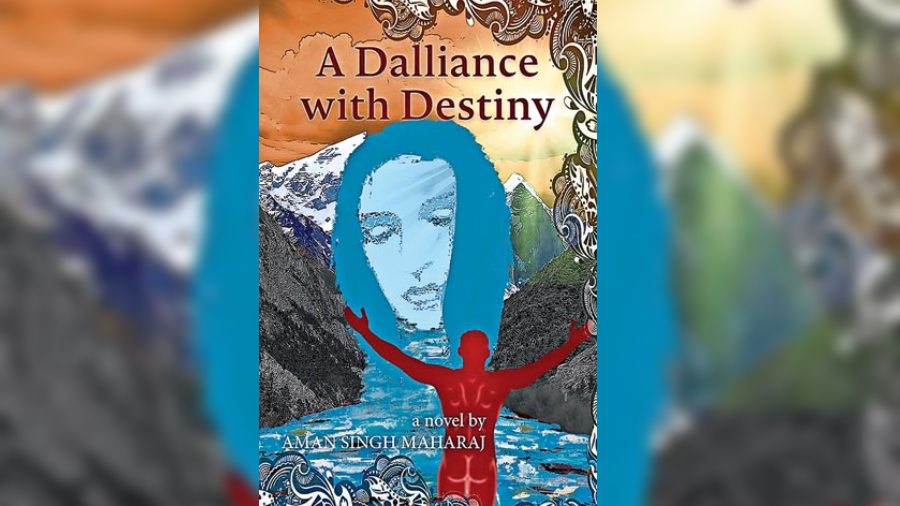

Launched earlier this year, A Dalliance with Destiny is a debut book by Aman Singh Maharaj that captures the journey of a man in his thirties fighting to remain lucid in a seemingly brash world. It is an exciting read about South Africa and India and the effects of colonisation. As we engage in conversation with the author, we find hidden analogies and intricacies of the plot. Excerpts from The Telegraph chat...

You have studied civil engineering, done an MBA, a PhD and then turned an entrepreneur and now a novelist.... Tell us how all this has culminated into your debut book A Dalliance with Destiny?

To be honest, my excessive studying and then breaking out into business was and is a means to live. On the surface, I do not think there is a link between my career choices and my writing. Perhaps, studying may have improved my writing skills, but, even then, the kind of style used in business versus fiction is vastly different. I guess it would be more fitting to say that writing is a passion, and being on a sound footing somewhat, financially speaking, gave me the space to focus on my writing. My mum first took me to the municipal library when I was five years old, before I could even read in fact, so this was the start of it all. I really do think that I read way too much as a kid, and should have focused more on playing sport.

Why did you choose such an intense plot with history, racism, colonialism as your debut book?

I believe that there is a story to be told about the Indian journey to South Africa many generations back, which has been done before, but I did not want typically pitiful characters to be the basis of the novel. Hence, I went with a very brash character, who is what he is, perhaps somewhat attributable to legislated prejudice. But history, racism and colonialism are only sub themes to the greater rubric of a guy seeking his epic life story, searching for meaning in his life, and an identity, which was arguably mangled somewhat, by the emigration of his ancestors. I do agree that the novel is very intense, as I do not see it as an easy read, but it is embedded in the kind of classical form of literature, however, using a contemporary setting.

Colonialism has a great impact on your novel, how do you think it has an impact on the women characters?

In reading the novel itself, one will see the actual transition of certain female characters as a cohort over the generations, from being subdued and almost meek, to their descendants coming off as crass and ultra-liberated, which is a trend, if I can call it that, that I have picked up from some female progeny of previously suppressed people. Personally, I do not find this paradigm shift very attractive, as, though I believe in the essence of a strong woman, it is more along the lines of the character played by Nargis in Mother India. The peak of the strength of Indian women showed best when they displayed their mantle as opposition to the British Raj in India (think Jhansi ki Rani) and the apartheid government in South Africa. Perhaps, though, that generation made the sacrifice so that this 21st Century Indian women could actually focus on developing sterling careers in industry, rather than having to fight some myopic, suppressive regime.

The plot is outstanding and is bound to leave the readers enthralled. Have you considered getting it made into a film?

Does it sound egotistical if I say that the idea of my novel being captured on celluloid crossed my mind many times, actually? I do not want to be falsely modest and say that this never occurred to me. The novel’s trajectory is epic enough to be turned into something cinematic. Whether it will be a South African film team, or an Indian one, is really dependent on who has the sweeping vision and the financial budget to do the movie. I think that the fact that most of the plot is set in India, will maybe influence the movie team. I even thought out who the actors might be, but it would require someone like a younger version of Nawazuddin Siddiqi, who is great at playing conflicted characters, and the same with a Dia Mirza, with her very vulnerable beauty.

This story obviously required a lot of research behind it, what kind of research did you need to do for the novel? Was it also inspired by personal events?

To be honest, I have been visiting India regularly since 1981, when I was an eight-year-old kid. So, I have a strong feel for the ethos of the country. Remember, as well, as a tourist one tends to see more of a country than the local, as one tends to travel around. So, I have been to virtually every state a number of times, with the exception of the far North-eastern ones. It usually takes me a week of being in India for my Hindi to flow smoothly again. I am a keen observer, and have the ability to be engaging a crowd, but still be watching an isolated incident through the corner of my eye, imbibing things as they unfold.

Whether or not there are personable events in the tale, it is difficult to say, but it is by no means an autobiography of any sort. All writers take incidents from events around them and then put these on steroids, so to speak, so that it has literary appeal. It really is all about how one ‘spins’ the yarn. To sum it up, I would say that the research was largely empirical.

Your readers must already be waiting for your next novel….

My heart breaks in that South Africa does not really have much of a reading culture any more. There are so many other forms of entertainment that are more geared towards giving one immediate thrills, while the essence of a novel is like a long-term relationship that requires commitment and nurture, in which, the delight is subtler, but ultimately more fulfiling. India, on the other hand, is much more geared towards the English practices of three o’ clock teas and book clubs. To be brutally honest, South Africa is not a knowledge-centric society — we are great at operational stuff, but not original in terms of creativity. To each his own, I guess.

I myself, perhaps, am a ‘racist’ reader, as I tend to read only works set on the Indian subcontinent. I find the way that Indian writers cast their English is a lot more lyrical in prose than the English writers themselves. Maybe this is due to the fact that Hindi as a language is so much more personable. For instance, every family relationship has a name, for example, while the English would simply say ‘uncle’ for all, in Hindi we would specify the relationship by saying chacha, mama, mausa, phoopha, etc. This kind of personable interaction seeps through osmotically in the transition from Hindi to English.

About the author:

Born in 1973, Aman Singh Maharaj lives in Durban, South Africa. A traveller with an avid interest in anthropology, he never ceases “to be enthralled by the sheer kaleidoscope of cultures, diversity and architectural marvels that the world has to offer”. After graduating in civil engineering, he did an MBA and then a PhD in the field of development studies, while working in diverse professions, including as an engineer and an economist, before finally choosing to become an entrepreneur. Quite enamoured by the concept of “magical realism”, he later decided to enter the literary realm. He also writes articles on various subjects, focusing mainly on the Indian diaspora, but he has now also forayed into more culturally generic topics.