What started as a learning centre for children of marginalised families during the lockdown has over the past year emerged as their second home.

Rokeya Shiksha Kendra in Patuli, which completed a year in February, had opened when a raging Covid pandemic had forced the closure of schools.

While digital learning was breaking new grounds, it seemed an alien concept for many children whose parents were struggling to keep the kitchen fire burning.

The schools have since reopened but the relevance of Rokeya — named after Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (1880-1932), Bengal’s pioneering Muslim feminist writer, educationist and activist — has multiplied manifold.

Titli Mistry (in yellow) with her sister Trisha at the centre

The students attend their formal school in the morning. Most of them come to Rokeya in the evening. Some of them who go to day schools attend classes at Rokeya in the morning.

Many students have evening meals at the centre.

The centre started with 40 students. Now, the number is over 160 — mostly first-generation students from families of unorganised workers in the neighbourhoods of Patuli, Kendua, Briji and Garia.

From a two-room flat on the ground floor of a house in Patuli, the centre has shifted to a new building in the same neighbourhood. There are two floors and six rooms now.

“Rokeya came into being while government schools remained closed for two long years, and simultaneously we got more and more engulfed in an atmosphere of hatred, division and misinformation,” said Kasturi Basu, one of the founders of the Humans of Patuli, the group behind the centre.

Students play chess at the centre.

The Humans of Patuli started as a citizens’ movement to resist the Centre’s citizenship thrust at the grassroots level.

The highlight of a daylong cultural programme — organised at a park in Patuli — on Sunday to celebrate the first anniversary of Rokeya was a play staged by students.

The 15-minute play, written against the backdrop of the climate crisis, was titled Jol boro na roddur. Two groups of students, representing water and sunlight, vied for supremacy. “I am tsunami,” exclaimed water. “I am stronger because I can cause global warming,” said sunlight.

Another group with booms and microphones, representing “contemporary media”, added more fuel to the rivalry.

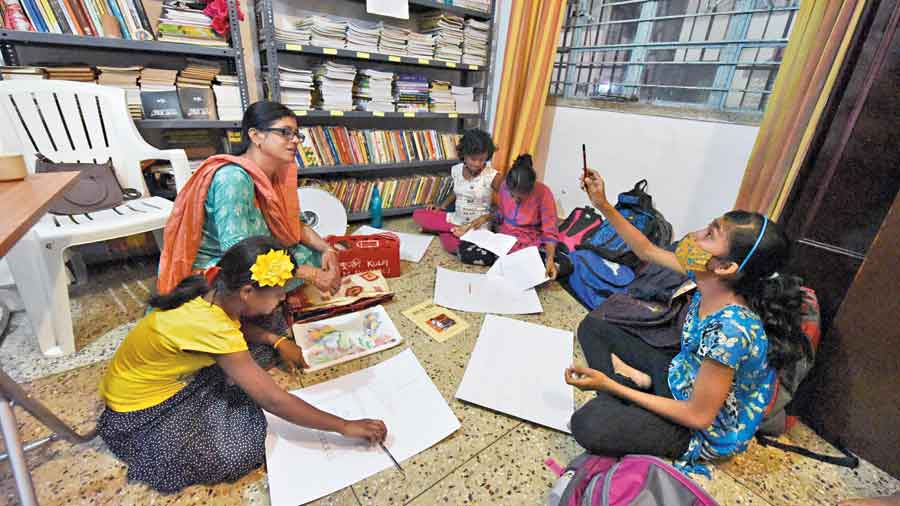

Students at a painting class at the centre

The play also weaved in the human tragedy brought on by the pandemic by portraying the loss of livelihood of people selling ice creams and pickles outside schools. The play mirrored the aspirations of people behind the centre.

“Rokeya desires to be a second home for first-generation students; a place where they will learn with joy, imagination and curiosity, as well as hold their community together with love and empathy. Where they will encounter science with fascination, history with fearlessness and explore all their creative faculties with abandon,” said Basu.

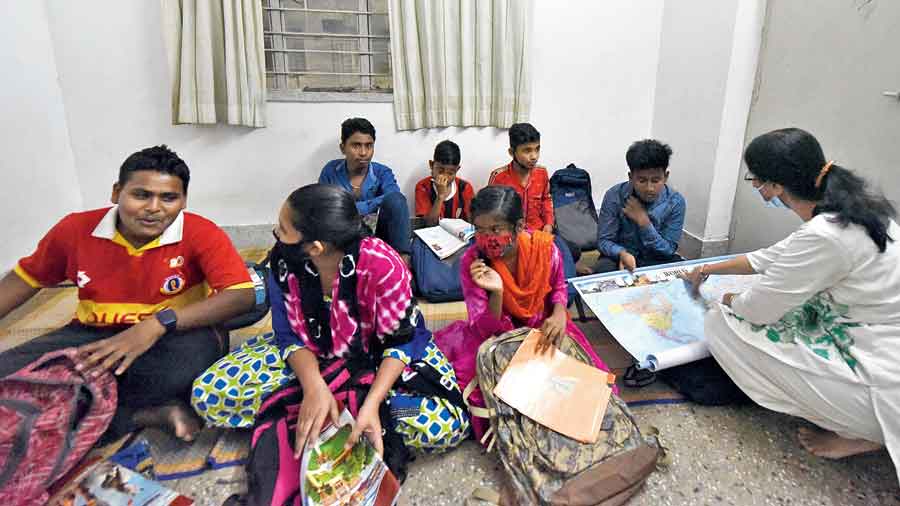

When The Telegraph visited the centre last week, a motley group of children — in classes IV and V — were attending a class on environmental science in a room on the ground floor.

The teacher was explaining “melanin as a pigment that gives colour to the hair, skin and eyes in humans and animals”.

On the ground floor, a couple of children were playing chess.

In a history class for students of classes VII and VIII on the floor above, the teacher was discussing the “Three Estates (clergy, aristocracy and the commoners)” of the French Revolution.

“What are we?” the teacher, Durba Mukherjee, asked the students. “Third estate,” said a chorus.

Since inception, Rokeya has also laid special focus on improving the language skills of the first-generation learners.

“Poor communication hampers the very base of learning in any subject. We organised remedial language classes to improve the communication skills of the students. Some of them, who used to dread reading a long paragraph, can now read a full page,” said Rupa Bhattacharya, language coordinator at the centre.

The students are encouraged to take up reading. Children’s films are screened on some weekends.

A library has been sliced out of a section of another room on the ground floor.

The monthly fee for students under Class VIII is Rs 50 and for those above, Rs 100.

“Theatre, films and music are an integral part of the curriculum here. They are not extra-curricular activities,” said Basu.

The spirit of Rokeya was embedded in Titli Mistry, 12. Deserted by parents, the student of Class VII lives with her sister and grandparents. Her grandfather is a rickshaw puller. Titli fetches water for neighbours and runs other errands to make some money. She also performs all household chores with sister Trisha and helps her grandmother in cooking.

She then attends school with her sister before coming to Rokeya in the evening.

Her prized possession is a pink piggy bank, in which she stores her daily income. The bank is kept at the centre. “The time I spend here is the best part of the day,” said Titli.