What started with a handful of people trying to find room under a flyover has now turned into a small settlement with over two dozen people.

At least five families have made a stretch under the Park Street flyover — opposite Metro Bhavan — their permanent home. The Telegraph visited the area to find out who these people were.

In the time this newspaper spent there, what emerged was an account of how this ‘colony’ kept increasing in numbers, catalysed by the loss of livelihood triggered by the pandemic.

The founder of an NGO that works with people living under the flyover said before 2020, around five persons used to stay under the flyover. The number has now shot up to 24, he said.

Most new arrivals were attributed to the pandemic.

Manju Clifton, in her late-30s, used to live with three daughters in a slum in the Dhalai Bridge area, off EM Bypass near Garia. She used to work as a help at a roadside eatery, one of many dotting the pavements of Chowringhee Road.

Her husband died in 2019. She lost her job in the summer of 2020, during the first lockdown. Paying a monthly rent of Rs 1,000 proved too much. One day, Manju left her one-room shanty for a new address under the flyover, where living would be free.

“Since I worked in this area, I was familiar with this place and its people. When I came here, I thought this would be a temporary address, until I found a new job. But now, I have grown used to this place,” said Manju.

Clifton is the surname of her late husband. Manju has since married another man. Her second husband works at a tea stall on the same pavement. All three of her daughters — aged 17, 14 and 12 — go to school. She is now pregnant with her fourth child.

For the residents, home means a patch of land. Four wooden stilts mark the boundaries of each patch. The stilts are meant for mosquito nets.

The area is surrounded by piles of shabby quilts, pillows and mattresses with many holes and an occasional trunk. The locked trunks are meant to store valuables — money and documents like Aadhaar cards and birth certificates of children.

Clothes hang from the boundary walls on both sides of the base of the flyover. ‘Kitchen’ means an earthen stove lit by firewood. The remains of a ramshackle wooden cabinet stores dry ration, potatoes, onions and some spices.

Adversity has pushed these people many miles back. Adversity has also brought out the best in some.

Sagina Khatun, all of 18, has four sisters — aged 16, 12, 9 and 7. Their mother died in the middle of 2021. Their father, an alleged drug addict, also lives under the flyover but has literally discarded the family, said neighbours.

Sagina plays both parents to her sisters.

Her day starts early with a visit to the flower market at Howrah, sometimes accompanied by Muskan, the younger sister.

She buys flowers, mostly roses, from Howrah and sells them at the south gate of the Victoria Memorial. On a good day, she makes around Rs 500. On an average weekday, she makes much less.

“This winter was good but then everything was shut again. I used to sell flowers on the Maidan then,” said Sagina.

She used to live at a slum in Akra in Santoshpur, on the western fringes of Kolkata. Her mother did odd jobs to make ends meet. As income dwindled during the lockdown, she started begging at a local market before shifting to Park Street.

Sagina did not read beyond Class IV. But she can write her name. “Hisaab ata hai (I can calculate),” she said with a smile.

Her younger sisters go to Kolkata Municipal Corporation schools.

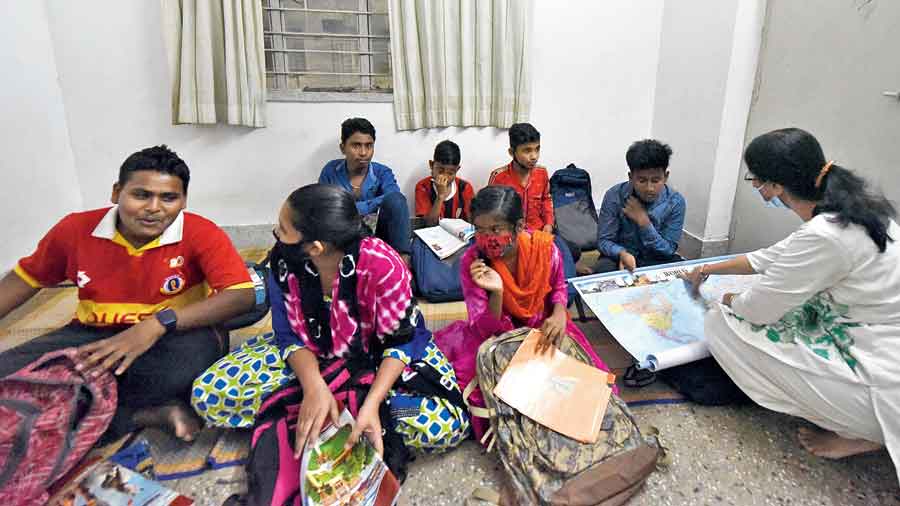

The families get support from an NGO called We - Together We Can Foundation. The support comes in various forms — groceries to tents for protection from rain to help in vaccination.

“We try to place the main focus on the education of the children here. We also involve women from our families to instil a sense of family planning in them,” said Anish Dasgupta of the NGO.

As buses, cars and cans sped past the roads on both sides, the women under the flyover sat at one corner for their daily evening adda.

Sagina braided the hair of Carmel, one of Manju's daughters. Manju kept chatting with Reshma Biwi, one of the ‘original’ settlers under the flyover.

“We don’t have anything, except each other. Living here alone would have been much worse,” said Reshma, 33, just before getting up to make arrangements for dinner. The menu — leftover rice, leftover dal and fresh alu chokha.

Many Calcuttans zip past these faces under the Park Street flyover every day. The Telegraph tries to find out who they are

Sagina Khatun, 18

Sagina lives with four younger sisters under the flyover. Her father has deserted the family and her mother passed away last year.

She sells roses at the south gate of the Victoria Memorial to make ends meet.

Her day usually starts with a visit to the flower market in Howrah, from where she buys roses. Before going to Victoria, she prepares breakfast for her sisters or buys them something to eat.

Sagina has not read beyond Class IV but she slogs every day to ensure education for her sisters.

“I dream of buying a small house. I want to spend at least one day there, with my sisters,” she said.

She is the toast of the settlement for her sense of responsibility. Other women take turns in looking after her sisters when she is not around.

For Sagina, entertainment means watching a film or some music videos on her phone.

Varun Dhawan is her favourite. Her mohawk haircut, she said, “is inspired by (rapper) Honey Singh”.

Reshma Biwi, 33

Reshma is one of the older residents of the area. She lives with her husband and two children.

Her previous home was a stretch of the pavement on Park Street, near its intersection with Mirza Ghalib Street.

“We came over in 2005, days after the flyover was inaugurated,” said Reshma. The Park Street flyover completes 17 years on February 19.

Her husband, Muhammad Afsar, washes plates at social dos, working for a contractor. But the pandemic has dried up his income.

Reshma cleans some offices at Chatterjee International and adjacent buildings.

By virtue of her long stay, Reshma is like a guardian for the rest of the women.

She has a 13-year-old daughter and an 11-year-old son. Her biggest worry is the future of her own children and other kids in the settlement.

“When we arrived here, there was hardly anyone else, other than a few addicts and vagabonds. I have seen this settlement grow. It does not feel right to see children ending up here. They deserve better,” she said.

Manju Clifton, 35

Manju left her rented shanty after losing her job at an eatery during the lockdown in 2020.

Her husband died in 2019. She somehow made ends meet but the lockdown came as a blow.

When she left home with three daughters, she was unsure of anything in the future.Two years since then, she has married again.

Her eldest daughter Mary, 17, goes to Loreto Convent in Entally. The next one, Carmel, 14, goes to St Thomas' Girls' School in Kidderpore and the youngest, 12-year-old Sania, goes to a school run by the civic body.

“I will ensure my daughters' education, even if that means going hungry,” said Manju.