At the beginning of the last century, many freedom fighters from Bengal were lodged at the Cellular Jail in the Andamans. Some died there. Now, the jail is named after not any one of them, but a co-inmate who sent five mercy pleas to the British.

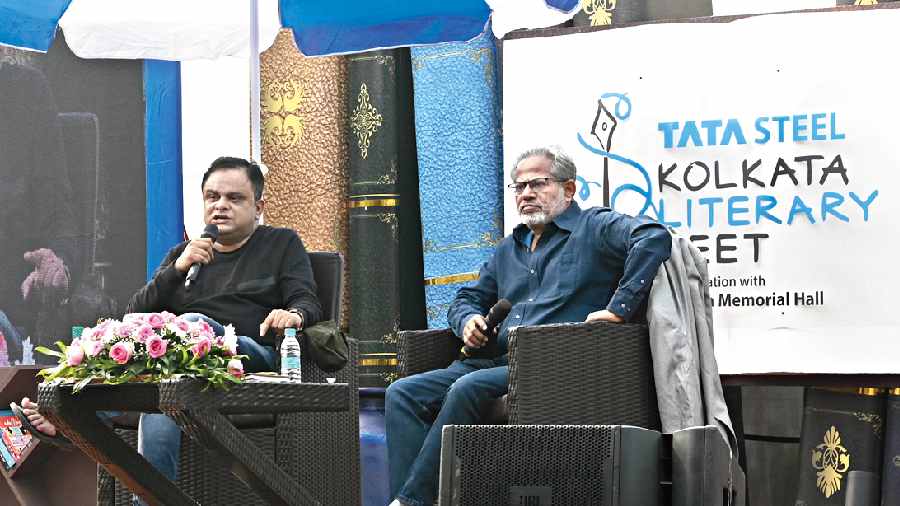

The “irony of time” was highlighted by Bratya Basu, actor, director, playwright and education minister of West Bengal, at a session on Day Three of the Tata Steel Kolkata Literary Meet, in association with the Victoria Memorial Hall and The Telegraph.

Basu discussed his anthology, Mir Jafar O Onyanyo Natak (which fetched him a Sahitya Akademi Award in 2021) with Subodh Sarkar, poet and teacher.

The back-and-forth movement of the past and present, which Sarkar said Basu had achieved consistently in his plays, was among the key areas of discussion.

“The past visits the present in disguise. The reality we see is fragmented. Often, to understand the present, you have to look back at the past. I have always wanted to see history in that way,” said Basu, before citing one of his earlier plays, Boma (Bomb). It is based on the Alipore blast case of 1908. Aurobindo Ghosh, Barin Ghosh, Ullaskar Dutta, Indubhushan Ray and Hemchandra Kanungo are the characters.

“Despite having done so much for the freedom struggle, they have been sidelined by history. When these men are languishing at the Cellular Jail in the Andamans... when Indu Bhushan Ray, unable to bear that torture, hangs himself, another inmate was also there.... He had written five mercy pleas to the British to get out of jail. His name is Vinayak Damodar Savarkar.

“Those who spent long periods at the Cellular jail, people who died there, none had the prison named after them. In Independent India, it was named after a man who sent five mercy pleas to secure his release,” said Basu.

Mir Jafar, first staged in 2018, is based on the events after the battle of Plassey (1757), which ended in the defeat of Siraj ud-Daulah in the hands of Robert Clive of the East India Company and changed the course of Indian history. Though Mir Jafar’s betrayal played a decisive role in the outcome, his elevation to power was short-lived. The Company soon replaced him with his son-in-law, Mir Qasim.

The name Mir Jafar, synonymous with treachery, is often invoked to describe the current political reality, which is marked by switching sides.

Basu read out a monologue from Mir Jafar, which he delivers towards the end of the play. Old and afflicted with leprosy, he still hopes that Mir Qasim will be “chased and killed like a dog” by the British and Clive will be forced to install him on the throne of Murshidabad. He wonders which way was the Lord taking him, only to answer the question himself: “To the chicken market”.

Basu again equated the past with the present.

“Now, if political ideology is dead, the politician is not the only one to blame. People are equally culpable. With the death of ideology, comes buffoonery, subversion and terror. If someone wants to force an ideology on a society that has none, it takes the form of religious opium. Mir Jafar is, to a large extent, part of that society. He has no shred of conscience and he is incompetent, but he still wants power at any cost,” said Basu.

While all the plays based on that period focussed on Siraj, the “much-vaulted tragic hero”, Basu made Mir Jafar his central character because he “mirrored the present subversion”.

Sarkar, a past winner of the Sahitya Akademi award, called Mir Jafar a “postcolonial text”.

“The subtext brings back and forth that time and the present. The past comes to the present and the present goes back to the past. This play comes out of history to mirror the recent times. In doing so, it becomes a postcolonial text,” he said.

He cited a scene from the play, after the battle of Plassey, where Mir Jafar is gorging on meat and Clive visits him to collect money. Clive claims his pie for placing Mir Jafar on the seat of power. “Ami commission nebo na (you think I won’t have my commission)?” he taunts Mir Jafar.

“It makes us understand that Clive represents a corporate entity. This corporate mindset is gobbling up today’s India. Religion is being used as a ruse to sell the country to corporations,” he said.