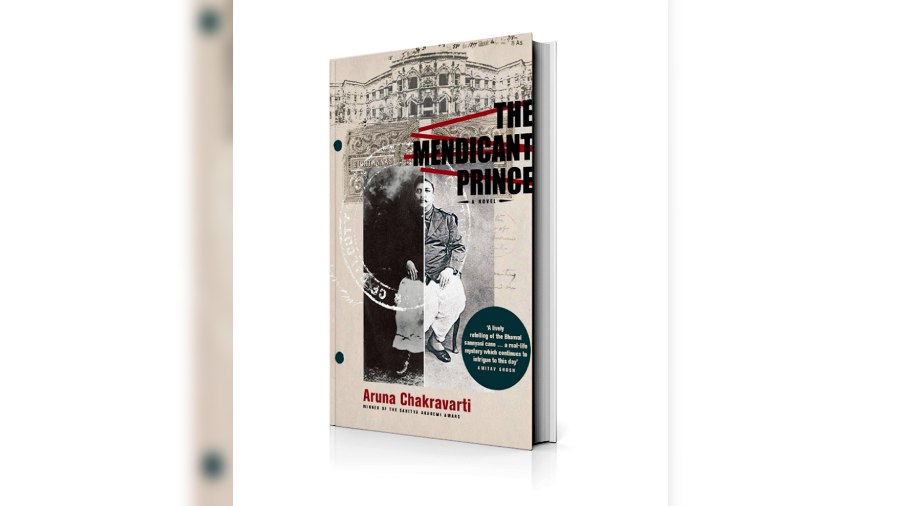

An addictive vintage of a racy old wine in a new bottle has popped up with The Mendicant Prince, ateasing, fictionalised and compelling retelling of the Bhawal Sanyasi case by seasoned author, translator and academic Aruna Chakravarti.

“The syphilis manifested itself in blistering pustules on his arms and legs and it was a terrible attack that made this second prince in line to the zamindari abhorrent to lookat,” was my gynaecologist and obstetrician father’s introduction to me to the Bhawal Sanyasi case,which was getting a resurrection in the vernacular press in Calcutta in the 1970s. I was just 16. And it was abrush with horror that wouldremain tattoed on my brain for a very long time.

A grandniece of Ramendranarayan Roy (the Bhawal Sanyasi) had consulted with my father and narrated her version of the story of her maternal grand uncle. And my father had usspellbound as he shared that tale with us when he returned from his chambers that evening. It was a mysterious, mesmerising tale which my mother, who was born near Dhaka in the 1920s, knew very well. And one that I would be disgusted by every time the story manifested itself in the form of a new film or book.

The most recent avatar of the Bhawal Sanyasi in popular cultureis the gripping film Ek Je ChhiloRaja (2018), which straddles two continents, two centuries and is the repository of unbridled sexual appetite, masculinist domination, scandal, Calcutta killings of 1943, colonial and postcolonial history and strong feminist theoretical constructs. As my father had narrated it, it was the story of atypical sample of a zamindar who was a brutal, lustful land owner and preyed incessantly on struggling, underprivileged, pre-pubescentwomen.

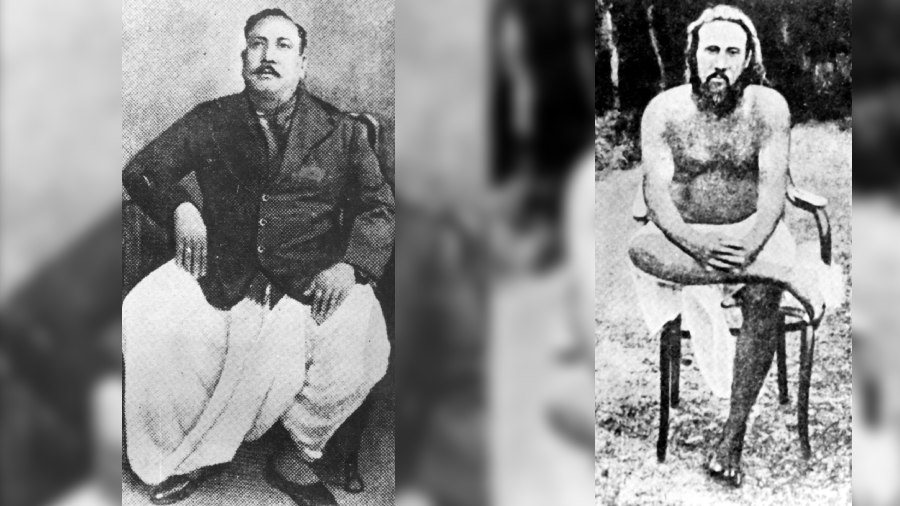

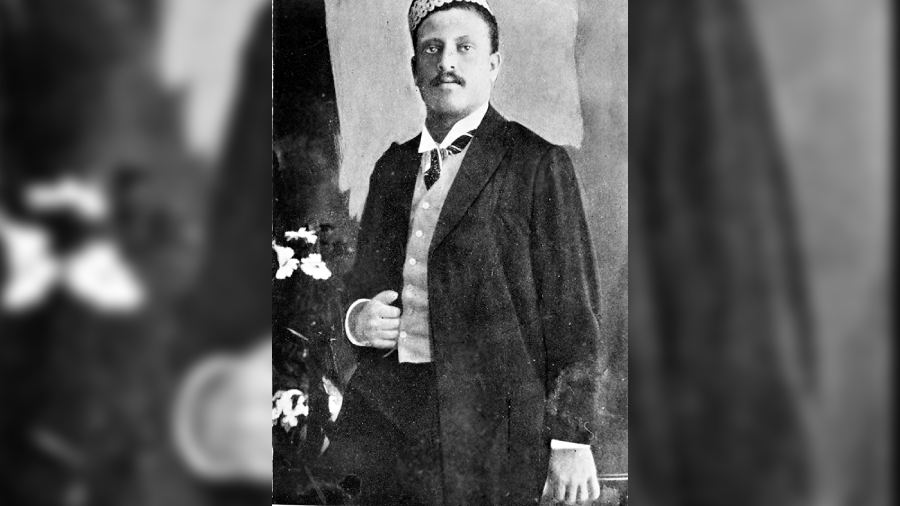

Of all the many published narratives that excavated the multitudinous aspects of what really was the truth, A Princely Impostor?:The Strange and Universal History ofthe Kumar of Bhawal, by renownedacademic, historian and writer Partha Chatterjee most powerfullyresurrected the frightening spectre,the egregious Ramendranarayan.Possibly poisoned by his wifeBibhavati and her brotherSatyendranath Banerjee and veryluckily surviving a botched-upcremation, the 2002 historicalaccount stuck closely to his return toclaim his estate 12 years after he hadbeen a wandering Naga sanyasi, ashe provided evidence in court.

The narrative as supported bythe court documents state that theuncremated “body” had been livingwith a mendicant sect that hadsaved him from the funeral pyre ona night when the rain had pelteddown and those who were supposedto carry out the last rites had fledthe freezing cold in Darjeeling.

It is useful to locate ArunaChakravarti in the literaryprofusion of the Bhawalpublications. Twenty years ago, in2002, Chatterjee in the preface to APrincely Impostor?, wrote: “Although the Bhawal case waswidely written about by journalists,pamphleteers, and bazaar writers,this is the first full-length book ofacademic history to deal with thecase.”

“The twin processes ofnationalism and decolonisation areespecially important.… TheBhawal case, I argue, was resolvedthe way it was, because it gotcaught up in this secret history ofnationalism and decolonisation,”wrote Chatterjee. “The truth ofidentity in my story is not just amatter of philosophical enquirybut of forensic knowledge.”

So how does history gettransformed into fiction?Historian, author and academicHarish Mehta says: “Within thebroad map of history based on factsand archives, the novelist zeros inon the smaller, unmapped, littleknownpeople and spaces, creatingthem through the novelist’simagination of what that actor/person might have been like, mighthave thought, the way they mighthave lived.”

So when there was a large andrich bag of literature that hadalready mined the Bhawal Sanyasicase intermittently over 100 years,why would Aruna Chakravartipresent herself with the formidablechallenge of finding a new angle toan old story that had been told todeath in books and films?

Chakravarti confesses: “Atfirst, I didn’t want to start on thisproject for the simple reason thatthe main storyline is known tomost people, particularly Bengalisof my generation. What could I addto it that justified a retelling of thestory. Then I thought how would itbe if I used a number of voices,each character telling part of thestory from his/her perspective?After all, many people wereimpacted by the events thatfollowed the alleged death andcremation of the Mejo Kumar. Hiswife, other women of the family,the subjects as well as the Britishrulers. Why not give each a voice?”

This would work in two ways.One, in the retelling the character’sown personality, individual traitsand interactions with others wouldbe revealed. Two, the reader wouldget several perspectives on the Prince. That would help inunderstanding not only hischaracter and personality but alsothe situation in general. This isclearly a piece of fiction, based on a real-life story.

Where Partha Chatterjeestrictly adheres to legaldocumentation that stretched to 26volumes that recorded theexchanges in court, Chakravartisays, “I believe that there is no suchthing as the complete or wholetruth. It is all a matter ofperception. People see things theway they wish to see them. Eachperson’s perception comes fromhis/ her experience of life and theirunderstanding of it. So, eachperson’s account though not thewhole truth contains part of thetruth. I am an objective narrator. Ibelieve in keeping my own voiceaside. It is up to the reader to readeverybody’s account and come tohis/ her own conclusion.”

And her strategy worked. TheMendicant Prince delivers a rich,polyphonic account of women’svoices to tell the story. On a closereading, the reader might feelsomewhat lost while floundering ina sea of information. The 278 pagesare encrusted with interestingnuggets. However, there seems verylittle trajectory chalked out for thelay reader. The Mendicant Princemight have benefited from abreakdown instated in a contentspage. The author does well toinclude an author’s note and a castof characters. The dedication to herlawyer grandson Nirbhay is afitting nuance to the legalscaffolding of this mind-bogglingstory.

An avid reader who believesthat keeping ahead of the game asan academic requires a voraciousappetite for knowledge,Chakravarti has used her time asan academic to enrich her writing: “Apart from what one reads inorder to teach, one also reads booksof one’s choice. I have always beeninterested in history and read a lot. Pure history as well as historicalnovels both in English and Bengali.So most of my novels are set in thepast. I don’t see any contradictionbetween the two. Teaching Englishliterature, which also needs anunderstanding of the time in whichspecific books were written, andwriting historical novels areactivities that complement eachother.”

A still from the 2018 film Ek Je Chhilo Raja that was based on the Bhawal sanyasi case

The principal of a Delhi University college for 10 years, anadministrator, a writer of 17published books, five of which arenovels, she is also the recipient of awards for her creative writing. The author has shown great scholarship and writing skills in creating sagas.How are her other stories aboutJorasanko and the Women of Jorasanko or the family saga TheInheritors, about her own family,similar or different to TheMendicant Prince? “They aresimilar in that they are true storiesbased on documented factsreconstructed through the light ofthe imagination.”

Historian Carlo Ginzburgmaintains in his study History,Rhetoric and Proof: “The idea thathistorians should or can proveanything seems an antiquated ideato many, if not downrightridiculous. I want to demonstrate inthe past that proof was consideredan integral part of the rhetoric.”

Says Chakravarti: “Whereas theJorasanko books were simpleaccounts of how life was lived bythe women of the iconic Tagorefamily, this story was areconstruction of a legal case.There was also a strange twist, amysterious element in the tale. Thesanyasi was recognised as thePrince by three courts, his subjectsand all the members of his family.All except his wife. Why was that?That was a moot question. That led me to explore Bibhavati’s characterin detail and try to understand whatmade her behave the way she did. Ididn’t want to demystify the eventscompletely so I hinted atpossibilities. That is also why I gaveher a prominent voice but didn’tgive the same to her brother andhusband.”

In the chapter titled Bibhavati Devi, the author presents a mothervs daughter struggle over thebrother Satyendranath who, assome accounts suggest, might havehad an incestuous relationship withhis sister Bibhavati. In her novel,Bibhavati, who was married at 13 tothe Mejo Kumar of the Bhawalestate, states: “Dada(Satyendranath) showed me theletters every time they came… Iclung to his arm and begged himnot to go. I would feel so lonely, sobereft. I said I would write to Maand implore her to let him stay afew more weeks. I understood Ma’spredicament. My uncles had lookedafter her when she was a young,helpless widow. But she wasn’t young and helpless anymore.”

And Bibhavati’s irate mother’srejoinder: “How will you secure alivelihood if you idle your timeaway sitting by your sister’s sideand holding her hand? Leave heralone, for God’s sake… have you noidea of how exasperated I feel by thetaunts and ridicule I have to sufferon your behalf ?”

Chakravarti explains: “My workhas always been gender-centric.When I translate I tend to pickbooks that deal primarily withwomen’s issues. In my creativewriting too I tend to make women’slives the central theme.”

This is where Chakravartiwields a different kind of wand.“Whether it is the way myforemothers lived in TheInheritors or the lives and times ofthe illustrious Tagore women or thewomen of the Bhawal rajbari whohave only been names so far. I havetried to explore their psychesthrough the imagination and triedto understand their motivationsand dilemmas. The Marxistconstruct that is the zamindarversus subject is also an importantcomponent of the novel as is thedilemma of a desperate Britishimperialism slowly eroding underthe pressure of an awakeningnationalism.”

The open-endedness of Chakravarti’s conclusion isstructured with intent. She seemsto chime with the early 20thcenturytheorist Roland Barthesthat with the death of the authorcomes the birth of the reader andthat the reader should be given theauthority to decide what kind of aman Ramendranarayan Royactually was. “Lastly, no one candeny the mysterious element of thecase. That had to be retained and Ihave done so. I have teasedpossibilities and probabilities butprovided no final answers toquestions.”

Ramendranarayan Roy was anincurable womaniser, whose entireexistence depended on the pleasurehe would derive from promiscuitywith nautch girls, prostitutes,domestic women staff, and, it wouldseem, any female he could pounceupon. Despite his wife, hardly past13, he was singularly focused onmultiple women for gratification.So how would the author react tothis kind of constant debauchery?

Chakravarti has no easyanswers: “A woman living in thesetimes and in my sphere of lifewould never tolerate a husband like Ramendranarayan. But we mustn’tforget that Bibhavati lived 150 yearsago. She was married at 13. She wascompletely dependent on somemale or other for sustenance as wellas protection. It had to be a father, ahusband or a brother. She chose herbrother. Had I lived at that timeunder the kind of pressure thatBibhavati lived, who knows how Iwould have reacted.”

Chakravarti says, "i believe that there is no such thing as the complete or whole truth. It is all a matter of perception. Peoples see things the way they wish to see them. Each person's perception comes from his/her experience of life

The Mendicant Prince (2022) Author: Aruna Chakravarti Publisher: Picador India Pages: 278; Price: ₹599

Aruna Chakravarti, author

JULIE BANERJEE MEHTA

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author ofDance of Life and co-author of thebestselling biography Strongman:The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen.She has a PhD in English and SouthAsian Studies from the University ofToronto, where she taught WorldLiterature and Postcolonial Literaturefor many years. She currently lives inCalcutta and teaches MastersA still from the 2018 film Ek Je Chhilo Raja that was based on the Bhawal sanyasi case English at Loreto College