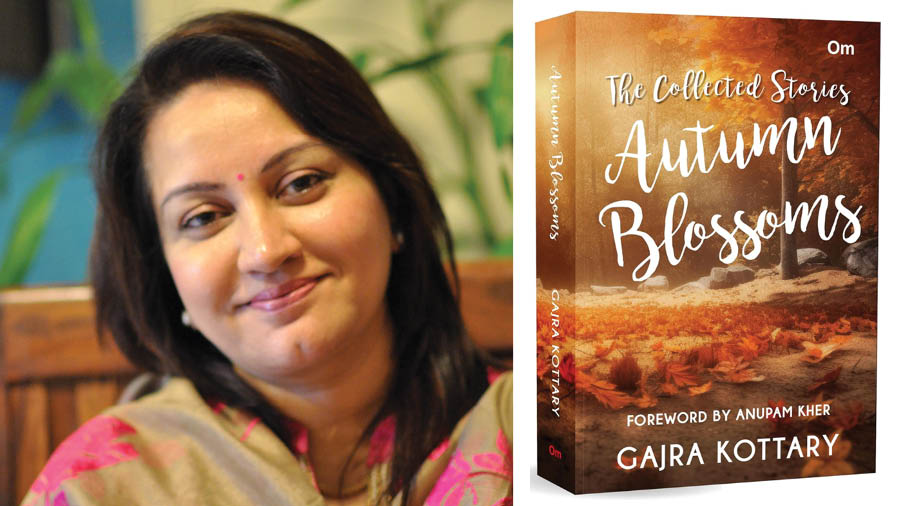

Gajra Kottary, award-winning screenwriter of some of India’s most popular television series, started out as a writer of short stories. With her sky-rocketing profile as a screenwriter – think path-breaking shows like Astitva: Ek Prem Kahani and Balika Vadhu – and her engagement with three novels published by HarperCollins Publishers, short stories took a back seat. Until recently. With Autumn Blossoms, published by Om Books International, Gajra Kottary returns to the short story. The 50 stories in this collection, divided into three sections, deal with woman protagonists coping with the vagaries of relationships with men, other women and themselves. An edited conversation with the author...

My Kolkata: You have been a screenwriter, novelist, and writer of short stories. How have these three aspects of writing influenced each other?

Gajra Kottary: Over the years, I think my experiments with one form of writing have definitely influenced the other. I have often been told by keen observers of my writing that it has become much more visual even in print after I became a scriptwriter. Writing for an aware and select audience for books keeps one’s thinking and imagination sharp. Helps one from getting complacent.

The visual aspect to writing… how does that work for you?

I do get asked this question often. And in trying to analyse my writing to answer it, I realise that even if it weren’t for my parallel identity as a writer for screen, I do have a propensity to think in pictures and scenes. And writing for the screen has only helped hone that ability. What screenwriting teaches you is literally and metaphorically to let your picture speak a thousand words. While writing a story for print, though the reader can’t ‘see’, even the description of a scene or a tangential reference makes them engage with the text and draw their inference about what the author is trying to say.

For example, there’s this story titled ‘Just for My Son’ where a mother is on her way in a train to visit her 18-year-old son in the city. She has heard that he is involved with an older woman, a divorcee, in the neighbourhood, and is determined to squelch this affair, which she is clear in her head is the doing of a desperate and immoral woman trying to seduce her son. But she also knows that it won’t work if she simply lectures her son to end the affair. She sees a young mother in the train deal with a mosquito troubling her sleeping infant. The young mother kills the pesky mosquito on the baby’s cheek, while rocking the oblivious baby back to sleep. Through this visual my protagonist conveys just what she intends to do without using the thousand words it might otherwise have taken.

Where do your ideas originate? With some examples of, say, ‘Not Man Enough’, or ‘Insane and Able’…

Actually, there is a story behind every story. But I can safely say that a lot of the stories have been triggered by innocuous newspaper headlines that kept dancing in my head long after I had read them as I kept imagining the drama behind the scenes of those headlines.

‘Not Man Enough’ was triggered by a newspaper story I read more than two decades ago… it was much before LGBTQ issues were even spoken about let alone being acceptable. I read a news item about two girls who ‘dared to live together’, refusing to marry others, and hinted at the trauma both of them had undergone in their so-called normal relationships in the village. It got me thinking, and it’s perhaps my only story in all these years that touches upon sexuality or the angst of sexual identity. In fact it was later published as a full-length novel by Juggernaut titled Not Woman Enough in 2021, with much more flesh and soul.

‘Insane and Able’ was triggered by a research article I read in a magazine about women who had been committed to mental asylums in India. Most of them had been dumped there by their husbands as a means of getting rid of them. They were not mentally unstable and were capable of leading a fairly normal life with a little help for mental health, but they had unfortunately become victims of patriarchy. I kept thinking of how unimaginably painful it must have been for them to live their lives there – the cauldron of anger, hate and helplessness would drive anyone to become truly insane sooner or later. But there’s a twist in the tale; being able to imagine that made me feel better and stronger about the lot of such women.

How did Autumn Blossoms come about? What specific challenges did you face in putting it together?

The stories span from the earliest years of my career in fiction, to the last of them which was written four months ago. I started to search for themes and patterns connecting and yet dividing the stories, as I had done for my earlier collections too. Since the number of stories in this one were much higher – 50 to be precise – my search for the common thread was slightly tougher. So I decided that while all the stories were bound by the thought of women’s true colours, especially the myriad shades of grey, emerging in the autumn of their lives, they needed to be segregated. And since my writing has been largely about exploring relationships, I decided to divide the book into three parts. There is a part about women’s relationships with men, another about their relationships with other women, and a third, most importantly, their relationships with themselves. But given that all these stories involve relationships with several dimensions, there is no watertight division.

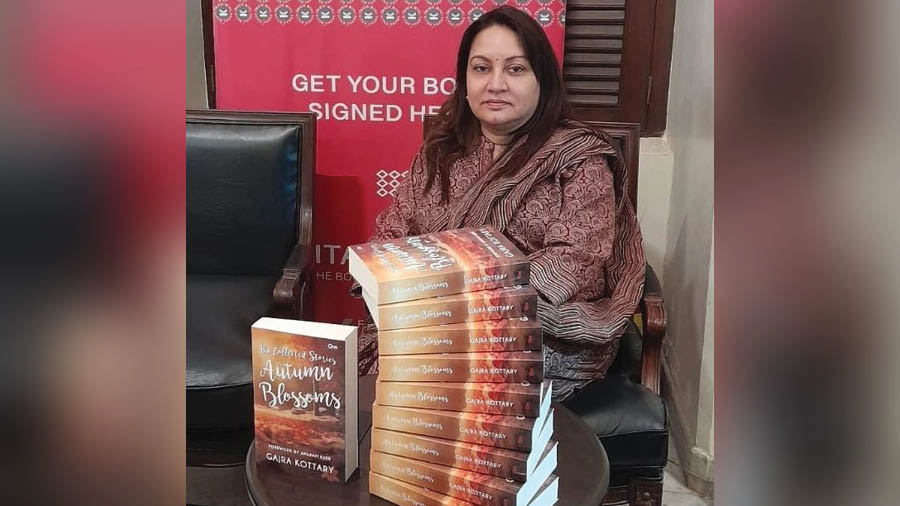

Kottary with copies of her book

Despite the strong feminine presence in a lot of your fiction, you are not stridently feminist – and the men in many of the stories get a fair deal. What accounts for this balanced take?

Honestly I am far, far away from being a man hater, I see sterling qualities in men and have admired and respected them as much as I have women. I think a good writer has to have that balance and consciously cultivate it if it doesn’t come naturally. I think in most cases men and women do need each other, they do need to get along with each other to create happy homes and eventually a happy society and world. That’s certainly my worldview and it’s a positive and optimistic one.

Also from a purely practical and selfish point of view, don’t we need to carry the men with us if we want to change our lot as women for the better, so why not convince them instead of alienating them? I am an intensely practical person so this balanced take is a logical one for me.

Let’s talk about the idea of beauty that features in many of these stories….

On a lighter note, show me one woman who is entirely happy with the way she looks! There is something I call the beauty conundrum. Most women have a complicated relationship with their looks, especially in these times, when standards of beauty have become so impossibly high.

Having been through many stages (and decades!) of my life, I have observed the complicated relationship that we women have with the way we look. Our self-worth comes from it and that in turn affects our relationships all around. As a teenager, the pursuit of beauty is agonising where one’s perspective could even be blinded as it happens in the story ‘Not Now’. As a young woman, it colours love, romance and passion and could have huge consequences in terms of life decisions – the case in point being ‘Return to Innocence’. And middle age brings with it a resignation and hopelessness with sometimes dramatic consequences as happens in ‘Waxworks’. Women struggle all through adolescence, youth and middle age, and only in the autumn of our lives, if that, acceptance comes about how we look.

Look at the beauty industry and the boom. What does it tell us? So even if I sound politically incorrect, I’d say it impacts the psyche of women and therefore their relationships, not just with men but also with other women and with themselves.

Novels, short stories, screenplays — which of these forms do you prefer most?

I love them all by turns. While the thrill of visualising characters and stories that you know will come to life on screen is definitely a kick, the joy of creating a world for posterity in the form of a novel is satisfying at another level. Short stories are the very spice of life. Writing short stories is challenging largely because of the thrift involved. At the same time it is also liberating – like you touch and go, not agonise about a situation. I don’t like to go back to the same form after finishing a project in one. Even a few weeks or months of change from one form to another is refreshing and also helps my mind not to get fossilised and make my writing go on autopilot.

Finally, what does writing mean to you and who are the authors that have influenced you?

At the cost of sounding a bit dramatic, writing is as important as breathing to me. It’s my ikigai… Rabindranath Tagore and Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay among the older Indian authors, Manju Kapur and Sudha Murty among the contemporary ones. Jane Austen, Roald Dahl and Anton Chekov among the older international ones and Elif Shafak and Khaled Hosseini among the contemporary international ones. I also like to savour the humorous effervescence of Moni Mohsin’s writings.