I, Pampa Kampana, am the author of this book. I have lived to see an empire rise and fall. How are they remembered now, these kings, these queens? They exist now only in words . . . I myself am nothing now. All that remains is this city of words. Words are the only victors.

—Victory City, Salman Rushdie

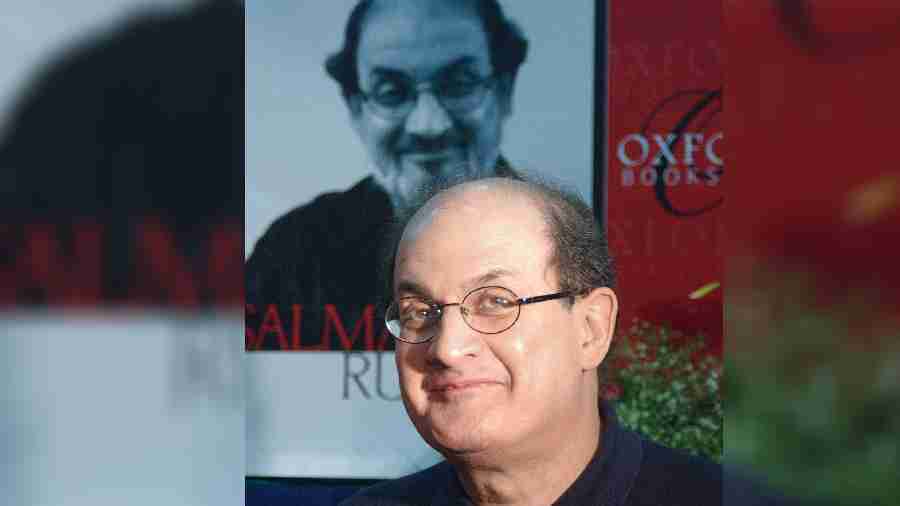

Brutally stabbed and partially blinded, Salman Rushdie was rushed to hospital last year. Since the assault on him in August 2022, the master storyteller who collapses the boundaries between the magical world and the real one like a jaaduwala has returned to his literary comfort zones — Indian history and magic realism — to locate his new novel, Victory City, on the founding and founders of the Vijayanagar empire. Released on February 7, this is a highly inventive and crisp story.

Rushdie had situated his blockbuster tale Midnight’s Children (1981), about two boys whose destinies had been exchanged at midnight of August 15, 1947, at the cusp of India’s freedom. Fraught and fractured, colossal and contentious, the Booker Prize-winning novel, Rushdie’s second, had retold a most significant story of modern India.

Now, in his latest book Victory City (Vijayanagar translated is ‘Victory City’), Rushdie finds a magisterial angle of glorifying the status of the divine feminine by elevating an unmatched, refreshingly empowered nine-year-old girl to the status of the sower of the seed of an empire and its ruler. He also shows us how the goddess Parvati breathed the force of the feminine through the persona of a pre-pubescent girl, thus at once blurring the borders between the divine and the human, as well as lending agency and power to women’s capaciousness for wisdom and governance.

In the story of young and heroic, feisty and super intelligent Pampa Kampana, Rushdie conjures a gripping tale — slightly mysterious, a deeply moving narrative that also sounds like Rushdie might have spent a few hours too many watching Padmavat and has an overdose of Rajputana tales of women committing jauhar.

Rushdie’s proclivity for viewing Netflix and cable TV notwithstanding, one symptom is clear. In keeping with the burgeoning trend among novelists to pay tribute to the feminine power in the universe — whether it is trees in Ben Okri’s Hallelujah for Every Leaf or the Mahaparvat in Amitav Ghosh’s The Living Mountain — for Rushdie too, perhaps the need to pay homage to the feminine force and her indomitable power to rule and nurture came to roost on his mind.

Victory City, Salman Rushdie’s book released on February 7, 2023

But there is more. What could be driving the project in Victory City is Rushdie’s ire and disgust at the treatment of women in Afghanistan. Rushdie has always been applauded for his fearlessness in being a rebel against colonialism, imperialism and patriarchy. The exceptional sutra that weaves the chafed fabric of the recent abject condition of women in masculinist, moribund rule of the Taliban might quite easily be seen to manifest itself with Rushdiesque creativity in the way he has implanted Pampa Kampana into the history of the Vijayanagar empire.

The storyline is lucid: Two Hindu kingdoms wage war in the usual historically recorded mode of the 13th, 14th 15th and 16th centuries. To escape from the rapaciousness of the marauding invaders, the women of the vanquished nation self-immolate on their husbands’ funeral pyres as they march en masse into a communal cremation tower in a practice known as sati that has been much maligned by postcolonial scholars.

Rushdie had the image of Vijayanagar for over 15 years in his head. He says it took him a long time to figure out who is going to tell the story. One of the most horrifying olfactory memories the reader carries with her is the nine-year-old girl Pampa Kampana carrying “the scent of her mother’s burning flesh in her nostrils”. The great goddess Parvati, one of the manifestations of the divine feminine, as the warrior goddess Chandi or Chamunda or Mahakali or Mahisasuramardini, says to Pampa: “In this exact place a great city will rise, the wonder of the world, and its empire will last for more than two centuries. And you … will see it all and tell its story.”

Pampa Kampana deputed two shepherds, Hakka and Bukka, to throw a handful of seeds at the spot where her mother had been cremated. The seeds, in turn, grew fully grown men and fully structured cities overnight and, thus, the reign of Pampa Kampana began. She was completely fictional and Rushdie says that he wanted to write a story about the south of India, being from north India, and a Mumbai boy himself.

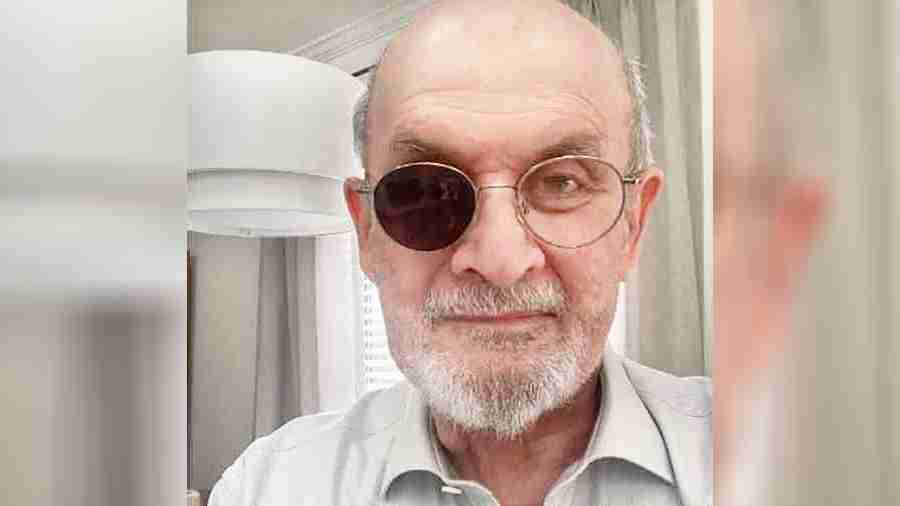

Salman Rushdie posted this picture of himself on Twitter to show how he really looks in February 2023 after recovering from the attack on him

According to epigraphic and recorded evidence, Hakka and Bukka were warrior brothers. The brothers wanted to build their own kingdom where people could live without fear. They collected a band of young men and trained them in warfare. They lived in a forest hideout on the banks of the river Tungabhadra in south India. In a strange twist of fate, and as if to bestow the fitting glory to the founders of the Vijayanagar empire, Salman Rushdie in Victory City has paid tribute to the brothers.

Speakers at the Vijayanagar Foundation Day organised by Haalumatha Associations in 2015 pointed out that historians had been neglecting the contributions of Hukka-Bukka, who laid the foundation for Vijayanagar, now a Unesco World Heritage site.

There is a signposting of feminine power right through the narrative. Far down the story, a monarch tells Pampa that her ideas are “a little ahead of your time”. A most unique kingdom with a formidable queen who lived through 250 years of its birth, rise and death, and which was preserved through her words, shines the light on the uncommon acumen of a weaver of stories from the footnotes of Indian history, often transforming history into a tale which is richer, more polyphonic, more crowded and more chaotic than could ever be transformed: “born full-grown from the brown earth, shaking the dirt off their garments, and thronging the streets in the evening breeze.”

Perhaps in Victory City, much like in Midnight’s Children, Rushdie has captured India and her multitudinous noises, smells, characters and cultures, and corralled her riots of languages and rituals, beliefs and colours, races and castes, in the way that only he could — with a veracity that has earned him the love, admiration and following in India and the world.

In an interview with The New Yorker last week, Rushdie said: “The first kings of Vijayanagar announced, quite seriously, that they were descended from the moon. So when these kings, Harihara and Bukka, announce that they’re members of the lunar dynasty, they’re basically associating themselves with those great heroes. It’s like saying, ‘I’ve descended from the same family as Achilles.’ Or Agamemnon. And so I thought, well, if you could say that, I can say anything.”

Rushdie has unabashedly maintained that fiction is not merely about documentation, and that stories don’t necessarily have to be only facts, although research is important too. Writers, he has said time and time again, use mythologies, fables and elements of the fantastic to create worlds, tales, narratives, and characters — of the imagination. For instance, by using fairy tales, he maintains, we can get to telling the truth in another way — “It is another door into the truth”.

And it is this telling of the truth à FROM P16 VIJAYANAGAR: AMERICAN TOURISTS’ FAVOURITE DESTINATION IN SOUTHERN INDIA When I first gaped at one part of a temple courtyard creation while visiting the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) in 1995, I could not believe my eyes. What I was looking at was a part of a Vijayanagar temple. The contested opinions of acquisition apart, the PMA has done a remarkable job in informing, educating and arousing the interest of many North American travellers and amateur art historians and South Asian specialists in the history of the Vijayanagar Empire. Since Philadelphia is a very close neighbour of New York, the granite pillars, brackets, and slabs that form this temple hall (mandapa) have whetted the appetite of hundreds of thousands of visitors who have been visiting Hampi and Halebid for many decades now. The majestic statuary and pieces come from the Madanagopalaswamy Temple, a Sixteenth-century building complex in the south Indian city of Madurai. (The complex is dedicated to Krishna and is still used for worship today.) As the PMA brochure clarifies: “The architectural elements installed here were purchased in 1912 by Adeline Pepper Gibson of Philadelphia while on a visit to Madurai. They are believed to have come primarily from a freestanding hall that once stood in front of the main shrine and was probably dismantled in the midnineteenth century. “The eight stone slabs between the pillars’ lion brackets depict scenes from the Ramayana, the epic tale of the hero Rama, another avatar of Vishnu. The slabs were originally part of a larger relief series that ran around the inside of the hall and narrated the entire Ramayana. “The life-sized figures projecting from the centralaisle pillars are deities and characters from both the Ramayana and another major Hindu text, the Mahabharata. These include Garuda. A variety of small relief images of divine and human figures also ornament the pillars, including Krishna as a baby, a couple making love, royal donors, and even the temple architect with his measuring stick.” The city was founded in 1336 by the sons of Sangama of whom Harihara and Bukka became the city’s first kings. In time, Vijayanagar became the greatest empire of southern India. By serving as a buffer against invasion by the Muslim sultanates of the north, it fostered the reconstruction of Hindu life and administration after the disorders and fissures of the 12th and 13th centuries. That change, in turn, stimulated new thought and creative productivity. Sanskrit was encouraged as a unifying force and regional literature thrived. Behind its frontiers the state prospered in great peace and prosperity. “on another level” in the genre of fantasy or fable, even, that has cost Rushdie so dearly. He was often oblivious to the indomitable and surreptitious presence of the fatwa — Rushdie had waved it away as no longer a threat in interviews since the late 1990s. But 33 years after the fatwa was issued, the demons still pursue him. Some of us have heard him say, “I am getting on with my life.”

Rushdie was always aware that some fundamentalist might try to kill him, but that never stopped the writer from creating stories that spoke out. And then suddenly, bang in the middle of a festival crowd, in a hive of activity in the innocuous western New York county of Chautauqua, where over 1,000 people were waiting to hear him speak, an innocuous man sitting in the audience vaulted onto the stage and kept stabbing him for 20 long seconds while astonished witnesses were left stunned.

Just when hundreds and thousands of readers were almost lulled into believing, just as Rushdie was, that the fatwa had faded into the twilight, the reality of the death sentence seems to have risen from a flicker of dusk. For his unflinching courage and commitment to talking back to masculinist domination and fundamentalism, after 33 years, Rushdie was assaulted brutally and suffered an injured liver and lost vision in his right eye.

Hadi Matar, a resident of Fairview, New Jersey, of Lebanese descent, a sympathiser of the Iranian military who committed the premeditated, heinous attack on Rushdie, is just the kind of person who was waiting to target this author for his truth-telling. Though some colleagues have criticised him for his “folly” at taking on the fundamentalist propagators of Islam, most fellow writers, activists, scholars, cultural producers, and universal fan following of readers, have applauded Rushdie’s abiding advocacy of free speech despite compromising his own safety.

Celebrated British novelist and his close friend Ian McEwan said Rushdie is “an inspirational defender of persecuted writers and journalists across the world” and actor Kal Penn invoked him as a role model “for an entire generation of artists, especially many of us in the South Asian diaspora toward whom he’s shown incredible warmth”.

In the conclusion of Joseph Anton: A Memoir (2012), his personal account of what it was to live in hiding for over a decade, a tale that was devastating in its intimacy and volatility, Rushdie wrote: “This in the end was who he was, a teller of tales, a creator of shapes, a maker of things that were not. It would be wise to withdraw from the world of commentary and polemic and rededicate himself to what he loved most, the art that had claimed his heart, mind and spirit ever since he was a young man, and to live again in the universe of once upon a time, of kan ma kan, it was so and it was not so, and to make the journey to the truth upon the waters of make-believe.”

And Rushdie has kept his ferocious spirit strong and burning. Six months after that horrible August day, his volition unwavering, his will to write unflinching, he has shown like his protagonist, the warrior queen Pampa Kampana of Victory City, that words and not swords are the cosmic arsenal. And light the sparks that preserve stories. And stories are the indelible magic that survive the vagaries of time.

VIJAYANAGAR: AMERICAN TOURISTS’ FAVOURITE DESTINATION IN SOUTHERN INDIA

When I first gaped at one part of a temple courtyard creation while visiting the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) in 1995, I could not believe my eyes. What I was looking at was a part of a Vijayanagar temple. The contested opinions of acquisition apart, the PMA has done a remarkable job in informing, educating and arousing the interest of many North American travellers and amateur art historians and South Asian specialists in the history of the Vijayanagar Empire.

Since Philadelphia is a very close neighbour of New York, the granite pillars, brackets, and slabs that form this temple hall (mandapa) have whetted the appetite of hundreds of thousands of visitors who have been visiting Hampi and Halebid for many decades now.

The majestic statuary and pieces come from the Madanagopalaswamy Temple, a Sixteenth-century building complex in the south Indian city of Madurai. (The complex is dedicated to Krishna and is still used for worship today.)

As the PMA brochure clarifies: “The architectural elements installed here were purchased in 1912 by Adeline Pepper Gibson of Philadelphia while on a visit to Madurai. They are believed to have come primarily from a freestanding hall that once stood in front of the main shrine and was probably dismantled in the mid-nineteenth century.

“The eight stone slabs between the pillars’ lion brackets depict scenes from the Ramayana, the epic tale of the hero Rama, another avatar of Vishnu. The slabs were originally part of a larger relief series that ran around the inside of the hall and narrated the entire Ramayana.

“The life-sized figures projecting from the central aisle pillars are deities and characters from both the Ramayana and another major Hindu text, the Mahabharata. These include Garuda. A variety of small relief images of divine and human figures also ornament the pillars, including Krishna as a baby, a couple making love, royal donors, and even the temple architect with his measuring stick.”

The city was founded in 1336 by the sons of Sangama of whom Harihara and Bukka became the city’s first kings. In time, Vijayanagar became the greatest empire of southern India. By serving as a buffer against invasion by the Muslim sultanates of the north, it fostered the reconstruction of Hindu life and administration after the disorders and fissures of the 12th and 13th centuries.

That change, in turn, stimulated new thought and creative productivity. Sanskrit was encouraged as a unifying force and regional literature thrived. Behind its frontiers the state prospered in great peace and prosperity

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author ofDance of Life and co-author of the best-selling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen.She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught WorldLiterature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches MastersEnglish at Loreto College