One of these days, someone is likely to mistake Khudiram for a retail shoe brand and Masterda to be the tailor’s assistant who measures body dimensions.

In an India obsessed with GDP growth and OTP pins, we have forgotten those who gave their lives for our freedom. We know little about them; our rewritten history books contain stray references; we revive their memories only after a relevant film has launched on Netflix; we are interested in them as long as the holiday announced in their honour does not clash with a weekend.

Irony.

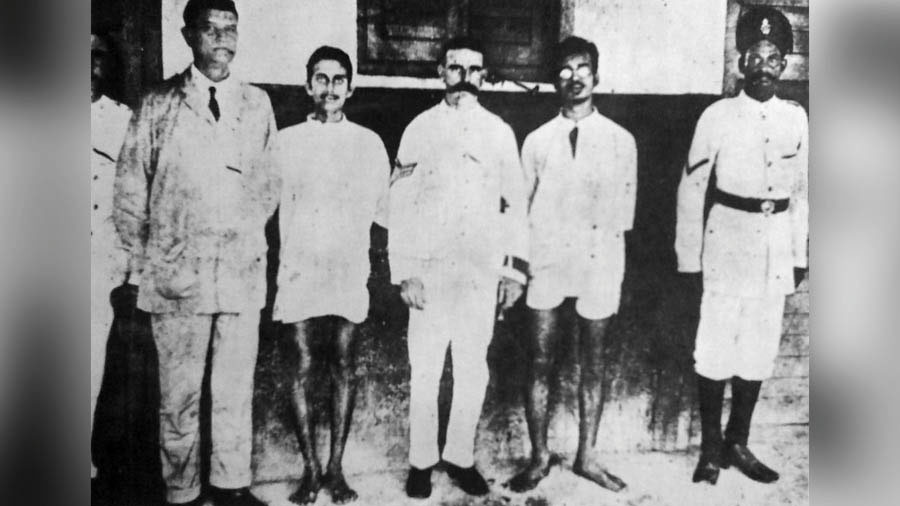

More than a century ago, a teenager could have pursued a chaakri but selected to make bombs in the conviction that this could earn freedom for his country. Baji Rout was 12, Kanaklata Barua was 17, Khudiram Bose was 18, Jatin Das was 25 when hanged or shot or arrested.

These young men and women were taking on the might of the British Empire at its peak with an icicle’s chance in hell; they were aware that their acts would not add up to make India free; they recognised that at most they would merely scratch the surface of the imperialist engine; they knew they could not go undetected or unapprehended for long.

And yet.

What was their junoon like? How did their minds work? What conversations did they have? With what kind of financial resources did they assemble weapons? Did some of these explosives blow up in their face? Did they wear gloves while putting the bombs together? How did they see the future pan out for their country? What did they think of those pursuing the same end through non-violence? How did they respond to the question ‘What do you want to become when you grow up?’ How did they explain their inexplicable absence from home? How did they protect their secret from probable informers? Which revolutionaries did they admire? How much of chemistry did they study to manufacture bombs? Where did they access bomb-making technology? Were they in touch with the Irish? How much did their ‘tutors’ know about related chemistry? How did they procure scarce ingredients? How did they take the news of the arrest of one of their accomplices? Did they meet each evening? Did they have code words that served as screen filters? Did they live in constant dread that their arrested accomplice may crack under interrogation? Did they shift homes and bases immediately following the arrest of colleagues? What was their regular income? How did they keep their expenses under control? How did they check the antecedents of those joining their group? How did they get word across to each other without meeting in person? How did they live double lives without raising suspicion? What code did they use in writing letters to each other? Did they have moles in the imperial government? Did their neighbours ever get to know? When someone suggested that they marry and settle down, what did they answer?

Questions.

Last month, I launched a movement to institutionalise the effort to celebrate their memories. In my own way.

I approached Bickram Ghosh and Tejendra Narayan Majumdar with an unusual request. Would they be keen to perform in the memory of all those who gave their lives for the country at the Alipore Jail Museum?

The result is that they performed last fortnight outside the Alipore Jail cells where were once imprisoned Subhash Chandra Bose, Jawaharlal Nehru, Chittaranjan Das, Bidhan Chandra Roy and Jatindra Mohan Sengupta.

This was not as much for music or melody as much for memory and gratitude. This ‘event’ was not for an audience; it was a private performance recorded, edited and posted.

The movement will hopefully endure. One will extract birth anniversary dates to rekindle the movement in the memory of freedom fighters outside the homes and in the neighbourhoods where they lived.

The memories may gradually turn sepia but must not be permitted to fade.

A nation that has forgotten where it came from may grow alright but remain prideless; a nation that is increasingly assured of its global importance must be perpetually reminded of its foundation builders.

If India — the fastest-growing global economy and the world’s fifth-largest economy — is positioned to lead the world out of a slowdown, then this may be just the right time to recall the giants on whose shoulders we once stood to look further and make this a reality.

We live because they died.