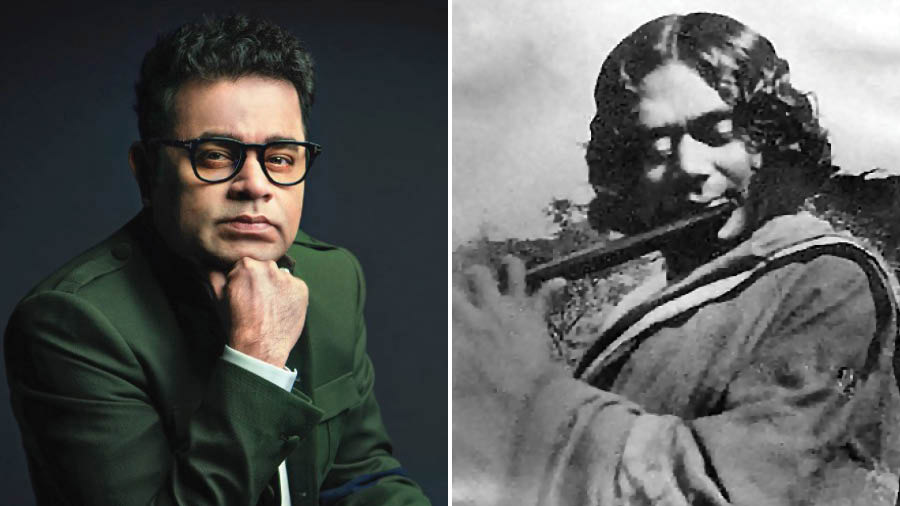

It was a cold November morning here in Seattle and I was looking at the dull, grey clouds in the vivid contrast of colourful, vibrant autumn leaves and trying to make sense of the cacophony in social, electronic, and print media around AR Rahman’s attempt to re-interpret Kazi Nazrul Islam’s “Karar Oi Louho Kopat – bhenge fel kor re lopat” (break, demolish those iron gates of the prison). While wondering what ‘patriotic’ songs really mean – in spirit, in rhythm, in format, in orchestration or in its rendition, the first song that reverberated in my mind was a version of Sarfaroshi ki Tamanna by none-other-than AR Rahman from the movie The Legend of Bhagat Singh. Much like many of his creations, this song resoundingly broke the prototype of patriotic tracks – moving above and beyond the thumping beats and marching tunes that we have been conditioned with. Sung by Sonu Nigam, Hariharan and others, Rahman’s treatment of this eternal classic gave it a divine, ethereal feel, delightfully blending classical notes in a soulful, understated way. I learned that one can beam with patriotism and yet be subtle and poetic about its expression.

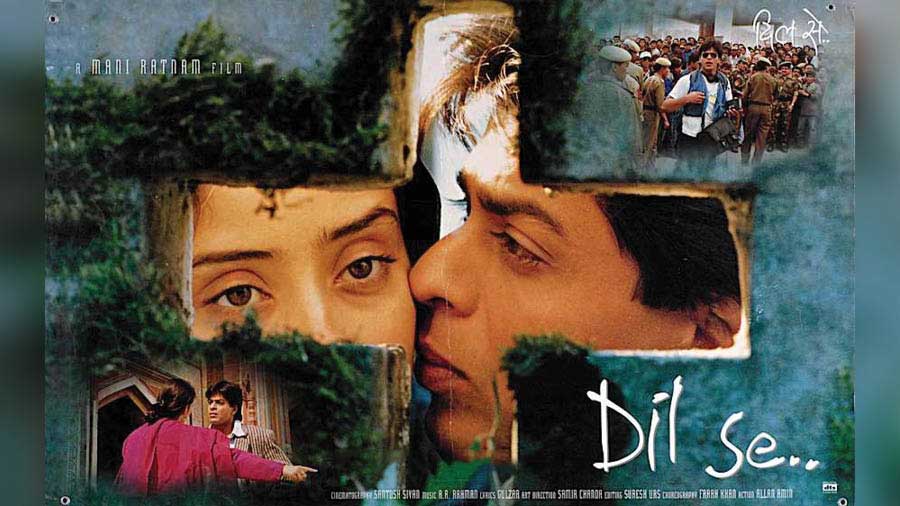

Growing up in the post-Independence era in India, where we did not really have a real external enemy or oppressor to fight or raise our voice against unlike the generations of legendary creators during the British rule, I would rate Rahman as the one composer who instilled patriotic fervour in the otherwise disinterested youth of our times, while breaking free of the usual formats of melody that we were used to hear. Who would have used wild guitar strings in the captivating background score of Rang De Basanti as a metaphor of the rockstar spirit of freedom fighters? Who would have powered the rustic chorus of playful villagers so emphatically to represent the vow to unite against all odds in Lagaan? Who would have chosen shehnai to depict mitti ki khushbu in the ever-mesmerising score of Swades? Rahman had the talent, vision and guts to raise the proverbial glass ceiling and shatter it into pieces with one timeless creation after the other, while re-writing the so-called grammar and rules of song-making. He consistently ventured into uncharted territories, embraced risks, and in most instances emerged triumphant, initial skepticism among some corners of critics and audience notwithstanding.

Despite such an impeccable ‘track’ record since his arrival into the music scene in 1992, Rahman’s latest interpretation of the much-loved, much-revered (and hitherto much-forgotten in terms of regular public discourse, if we want to be honest) classic penned by Kazi Nazrul Islam may not have worked for a section of listeners, may not have lived up to the expectations of many and may also have appalled a section of the Bengali-speaking audience who relate with the original composition with a certain sense of pride and valour. The essence of the original composition and the vibes most people associate this song with may also have been “lost in translation”. Having first read this poem as an integral part of the school textbook during my elementary school days in Kolkata, I can relate to the generic sense of discomfort and disappointment around the tune structure, composition, and flow of the new version. What I fail to relate to though, is the vitriolic hyperbole, courtesy in parts to the proliferation of communication channels, that appears to be misdirected and devoid of respect, and empathy, in most part. I am hopeful that a creative genius such as AR Rahman will filter the noise from the feedback around, incorporate constructive suggestions, and move onward, and upward.

A strange aspect of the human psyche is the tendency to recognise legends primarily in retrospect. There is also an inherent bias in going overboard in glorifying the past and undervaluing the present. That said, and acknowledging that some might find this analogy difficult to accept, I find it striking to note how rebellious both Rahman and Nazrul Islam have been, in their own distinctive ways, in their respective eras, in breaking free of traditions, rules and regulations. I hope it is about time we shatter the shackles of our own limitations in being more open about creations and interpretations that may not be in sync with our prior conditioning and expectations. I have a feeling that Kazi Nazrul Islam – the visionary that he was – would have been a strong advocate of breaking free of the usual format of song-making and may have been more magnanimous about Rahman’s interpretation than some of Kazi’s self-proclaimed followers.

It is only if we exterminate “surer oi louho kopat” (iron gates around compositions?) and celebrate apparent failures that we will liberate the current and future generations to be fearless game changers in music and beyond. Some of the attempts to reinterpret cult classics or to create new forms of music will fail miserably, some will disappoint, but some will resonate, and some will live on for generations. Let’s ensure we set the pitch right even as we register our protest. Let the quest for harmony triumph over unhinged hatred. Jai Ho.

Dr. Ananda Sankar Bandyopadhyay is a global expert in infectious disease epidemiology and vaccinology. He has written peer-reviewed articles, book chapters and perspectives in leading journals, newspapers, and media portals across the world. He has also written commentaries on issues such as medical education, music and films. You can follow him on Twitter: @anandaonline