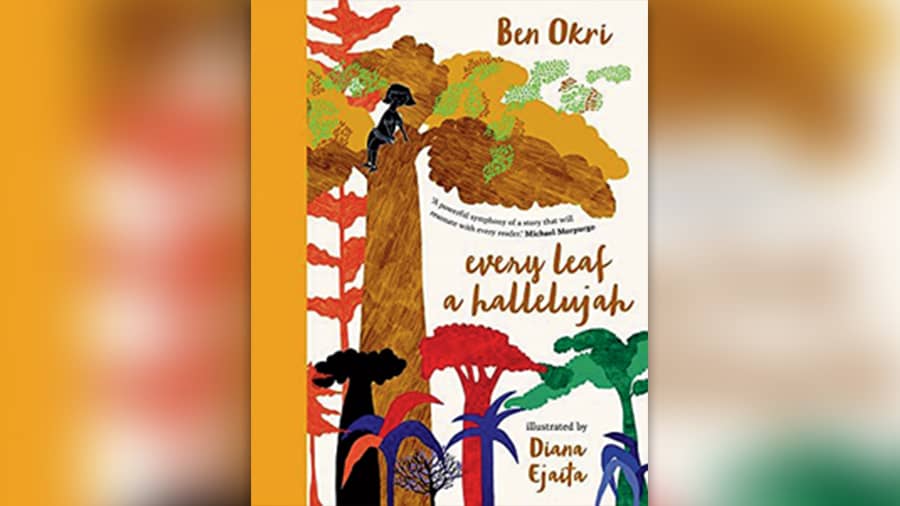

Poverty, hunger and death, have always been in an everlasting dance with the joy of living and the beauty of nature in Nigerian Booker Prize winner Ben Okri’s fiction and poetry. Now, with his handsomely illustrated and endearing environmental tale for children and adults about the healing power of trees — Every Leaf a Hallelujah — Okri’s faith in nature has seized the imagination of the literary world.

All of last week, searing images of floods that rendered hundreds of Nigerians homeless and drowned others has shone the spotlight once again on the egregious Nigerian administration that has kept to the highest standards of neglect and brutality on its citizenry. Now, more than ever, the Nigerian-born writer, a courageous and formidable voice for over four decades against the abject poverty and despair of his birthplace, is being lauded for his unmitigated criticism of the Nigerian crisis.

The strong political message in the Nigerian-British novelist, poet and dramatist’s earliest novels has only become more forceful and persuasive over the last four decades. If the greatest writing comes from the greatest pain, then this formidable thinker and storyteller has, with his inimitable style and universal content, transformed into a voice that is, to invoke the title of one of his novels, ‘astonishing the Gods’.

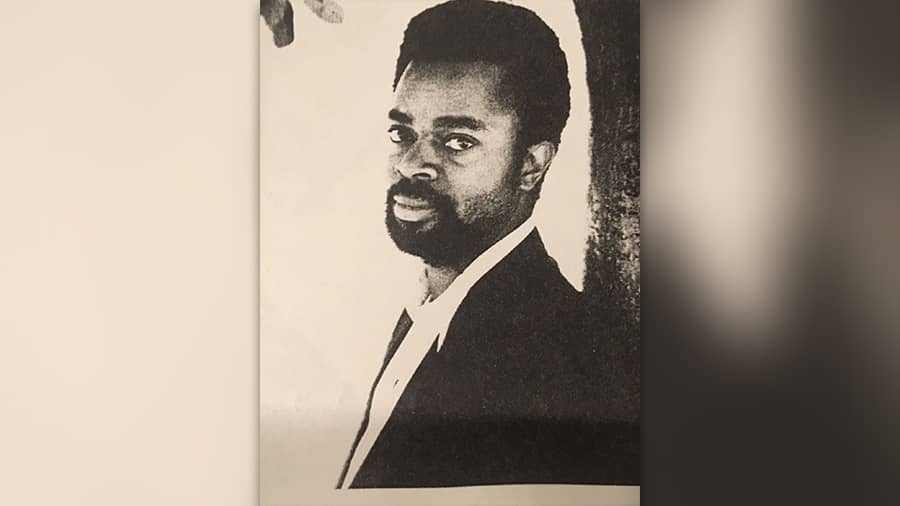

This year marks a kind of watershed in many respects for this fearless writer who has been the unofficial legislator of humankind ever since he published his first novel at 19. In 1991, at 33 years, he won the Booker Prize for The Famished Road, a riveting story narrated by an abiku or spirit child.

Thirty years on, and Ben Okri is only getting better at spinning the powerful off-spinner that compels the reader to read, pause and take stock of our increasingly dodgy world, the constantly queer pitch that spells horror, injustice, poverty, hunger and bloodied histories of those who struggle to survive a barrage of unrelenting daily invasions.

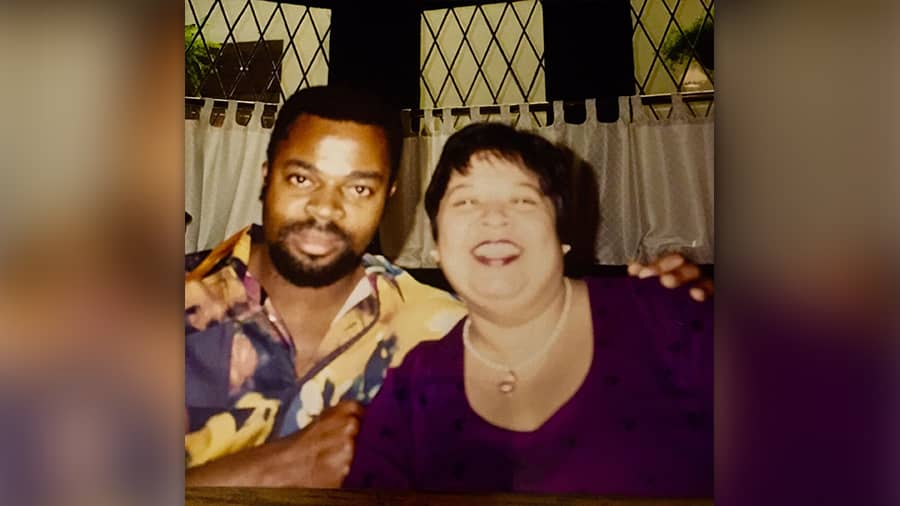

For me, this year marks a milestone of sorts. It was 26 years ago that I met the Nigerian writer who had just published his 10th book, Dangerous Love. What struck me was that extra moment he spent holding my hand in a memorable gesture of warmth.

Meeting Ben Okri and being in conversation with him over three days in Singapore years ago, left a distinct impression on me

It was 1996 and it was a warm and welcoming Singapore. As the chair of the Tanglin Club Library sub-committee, I had extended him an invitation to meet the burgeoning readership that gave him a hero’s welcome.

In my line of work as a literary reviewer and interviewer of Nobel laureates and literary stars, I was surprised by his humility: “I had once said years ago that when I complete my tenth book I could claim to be a writer, With Dangerous Love, I suppose I can assert that claim.”

While speaking about his life as a boy in the 1970s in his birthplace, Minna, in south Central Nigeria near Lagos, Ben Okri’s voice became wistful. “I remember seeing fathers of friends, mothers and sisters being dragged away and beaten up, young men being killed and thrown into the river.” His earliest memories, he said to me, “are walking on the edge of a desert, a little town that grew groundnuts, that was hot, very hot. I remember walking between giants in Minna as a little boy.”

The oral storytelling techniques of the oldest civilisations find wondrous manifestations in Okri’s oeuvre. And the African imagination is alive in Okri’s inventive and innovative employment of juxtaposing the world of the spirit and the world of realism.

A master craftsman of magical realism as a technique to tell a story, in the tradition of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Salman Rushdie, Zulfikar Ghose, his contemporaries, Okri showcases a remarkable capaciousness to embrace two worlds simultaneously ini The Famished Road, written in 1991, and now in For Every Leaf a Hallelujah, written in 2021.

Post-colonial theorist and guru, prolific writer, renowned academic and specialist of African literature, Ato Quayson argues: “In The Famished Road, the entire work is narrated by Azaro, an abiku (child trapped in cyclical reincarnation), who maintains contact with the spirit world while steadfastly being committed to remain in this one.”

The curious thing though, and that gives the novel a strange and unsettling quality, is that not only does Azaro move freely between the two, and the mode of movement is not within the rational control of the child, but there is immense fluidity with which the reader travels between the two worlds with Azaro. In Every Leaf a Hallelujah, Okri once again becomes the wizard who takes the reader through the experiences of seven-year-old Mangoshi on a magic carpet ride to the wise and wonderful world of trees.

Now, eco-criticism is being used as a tool to wow the reader by many writers who have jumped on the bandwagon of political expediency. Okri has been a strong proponent for 40 years now and has been a powerful voice for biodiversity and sustainable development. In his remarkably lucid essay on Food, Ritual and Death, in a 2015 special volume dedicated to Ben Okri, Callaloo, a renowned journal published by the Johns Hopkins University, the author argued persuasively on the aspect of ecology and the sustenance from green things that grow and nurture human beings. “The plants and animals from which we derive our nourishment have been here longer than we have. They are requisite for our existence. Our being is contingent upon them. They on the other hand are contingent upon sunlight, water air and earth… food therefore is a repository of the magic of sunlight, the mystery of water, the omnipresence of air, and the steadfastness of the earth, which was once stardust, the gold of the sun, the vitality of the air, the secret power of water.”

“It is curious how food features in images of the immortality of the soul… At the false doors of Egyptian tombs food was left for the dead. Their spirit was supposed to eat from beyond. We believe deep in us, that food not only nourishes the living but also the dead. In that sense, food partakes of our intuitions of immortality.”

In 1991, in his address to the Booker Prize committee at the acceptance ceremony, Okri recited a poem, which had the audience visibly moved:

“We are the miracles that God made to taste the bitter fruit of time.

We are precious and one day our sufferings will turn into the wonders of the earth”.

What undergirds his prodigious wealth of writing is a spirit of lightness and a vision of hope in a blasted heath that is the world today. That is why “our music is so sweet”, the writer says to us, “It makes the air remember there are secret miracles at work”. In a planet in turmoil where we are still in denial, as an unacknowledged legislator for human kind, Ben Okri is the messiah of faith in humankind’s covenant of grace.

“In Africa we have a saying, ‘If our ancestors eat, we eat. If the unborn eat we prosper’. Food connects us to past, present and future. It can be said that food is more than the gift of the gods. It is the essence of the gods.”

Pictures courtesy the author & Getty Images

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Kolkata and teaches Masters English at Loreto College

A Forest Fable

Exactly 30 years after he wrote The Famished Road — narrated by the spirit child Azaro — that won Ben Okri the Booker Prize in 1991, comes Every Leaf a Hallelujah, a magical forest fable about a seven-year-old girl. Little Mangoshi, who has the Herculean task of bringing back a healing flower from the neighbouring forest, the only “medicinal element” that will cure her dying mother, and the entire village discovers that she has the gift, like Saint Assisi, to hear the language of the natural world.

Mangoshi and her ancestor Azaro from The Famished Road almost immediately came together for me. This timely eco fable (as some reviewers have called it) was electric in its grip. Okri’s lucidity in narrating a simple story about what the next generation might be able to do to bring kindness and compassion back to our relationship with nature and his use of childlike wonder and innocence to unveil the promise of a brighter, kinder world unveils the sorrow of a wounded world to any reader — a child, a young adult, any adult.

Ben Okri and Diana Ejaita, the highly talented illustrator, have created a magical world of mystery, magic and colour in this beautiful book. The beauty in their collaboration comes from a deep sense of commitment to the preservation of nature and the forests, coupled with the urgency to imprint upon the younger generation the need to right the wrongs of our generation and the generations that have raped and looted the planet.

An extraordinary collection of speaking trees, each with its own persona and voice, impress on Mangoshi and, through her, the reader, of the immediacy of conservation of the forest. The chief among them, the great baobab, invites the reader into his branches to travel the world and see for ourselves “the perils of not listening to nature. All around us, forests are vanishing, and no one is listening”.

In his note to the reader, Okri prefaces his book with a clear, simple trajectory: “When I was young I thought the beauty of the forest would last forever. Now I am not so sure. Certain grown-ups, who have forgotten their childhoods, and who care more about money than nature, are destroying the forests.”

The gentle admonishment at the end of the note to the young reader is both inspirational and invokes a spirituality that marks all of the poetry and fiction, essays and drama by this visionary writer: “I hope you love trees. They are not what they seem. They are magic and they touch our lives with magic too.”

Okri presents a compare and contrast picture of the forest and surreptitiously draws the reader to a deeply philosophical conundrum: The first time she goes into the forest to seek the healing flower, Mangoshi loses it and is unsuccessful in her mission. However, she discovers her gift to be able to speak, listen and communicate with the trees, all lush and thick with healthy leaves and strong trunks and flowers.

They rally around her but utter the sentence that Mangoshi is not yet ready to be told their concern. Mangoshi returns home to her village in Africa, which borders the forest. The forest could be anywhere on the planet, the village too, and Mangoshi might be a little girl in the Sunderbans or the Rockies or the Andes.

Her mother’s health worsens daily and as life gets in the way, little Mangoshi’s wonderment and urge to visit the trees in the forest diminish gradually. A year passes. One day, her father presents her the option to go to the forest again. Okri has once again created a family that empowers the little girl child — never forcing, not even cajoling, but allowing Mangoshi to make the decision whether she would like to go or not.

By bestowing on his protagonist the agency to choose, Okri empowers the highly sensitive and intelligent young girl. She is far-thinking and knows she is required to bring back the healing flower, even though it is a mammoth task. This time though, the forest is close to a blasted heath with the sign of human encroachment and greed.

As the seven-year-old Mangoshi stood among “the broken trees” and “the wrecked land”, the forest which was normally alive with bird calls and animal grunts and the whizzing of insects was deafeningly quiet.

Every Leaf a Hallelujah is a song of praise to the living universe, but it is also a celebration of the promise of compassionate regard to save the planet, making the new generation accountable and responsible in its incredibly challenging task.

A NOVELIST AT 19

The Nigerian Civil war painted an abiding dark cloud on Ben Okri’s life. He finished his secondary school education and wanted to study physics and become a scientist. But he was deemed too young then for university and that summer he read his way through his father’s library and found his true vocation.

He began writing at a very early age. He began with poetry and then published articles and essays about the living conditions of the poor in the slums of Lagos. Then he wrote short stories and eventually what was to become his first novel, Flowers and Shadows.

In 1978, Ben Okri returned to London. He studied comparative literature at Essex University. Two years later he published his first novel Flowers and Shadows and, in 1982, came his second novel, The Landscapes Within. He went through a brief period of homelessness. In 1986, came Incidents at the Shrine, a collection of stories that won him prizes and enhanced his reputation.

In 1988 a second collection, Stars of the New Curfew, cemented his reputation as a powerful new voice. And then in 1991, he truly hit his stride with the publication of The Famished Road, that won him more than popularity and the winnings. It earned him the attention and respect that he deserved.

By his own admission, Okri says he wrote the first draft of his first novel in a ghetto in Lagos, working on it at 4am. His family remembers that he began reading The Times at around the age of four.

“At school in London I was that kid who stuck his hand up to read aloud from the Shakespeare play we were studying or to recite a poem. At secondary school, in Nigeria, literature was something, he says, that he was “negligently good at, but didn’t take seriously”.

During vacations he would voraciously read at the libraries of foreign embassies and at the American Library he encountered Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman; at the Japanese embassy, he discovered karate, Zen Buddhism and Basho. “It seemed then I was destined to be a scientist. I applied to university, but at age 14 was deemed too young. I spent a year at home, waiting to be old enough.”