Your great-grandfather was building a whole damn house when he died, baby-love!” my father liked to remind me. “Raos never rest!”

Being a Rao, my father felt, was the one monumental fact from which everything else had derived. He had been born Dalit, but because his family owned the Garden, they had allowed him to go to school instead of laboring in the fields. From that education, he had earned marks high enough to gain acceptance to one of the best universities in India, where he thrived; had been recruited to graduate school on scholarship at one of the most selective institutions in the United States; and had co-founded one of the earliest computer companies and grown it into the most valuable corporation on earth. And then, at an age when most men are well into their retirement, he had rescued the planet from nation-state rule, which was bringing society to ruin, and engineered a calm and peaceful transition to Shareholder Government, under which the world’s citizens collectively owned its corporations, each Shareholder as able as the next — indeed as able as King Rao himself — to build a life of happiness and success.

Shareholder Government had been built on what King considered the most important truth of modern life: that any person possessing capital can, with effort and ingenuity, succeed. But you had to stay on your guard. He, for one, would not slide into complacence, would not age into some soft, toothless armchair dweller. He considered relaxation a synonym for lazing. Retirement was a nice word for quitting. “I won’t sit around like a quiet retiree,” he proclaimed. “I have a lot to do!”

I admired him for that. As for what exactly he did, I knew only a little. He had designed our house in the spirit of the one in which he’d been raised, a modest single-story, railroad-style construction with a wide veranda on either side. He’d built it near the northwestern end of Blake Island, in a clearing where trees had been felled long before his arrival, when the island had belonged to the state government. Next to the house stood a small garden and orchard in which my father grew tropical produce from climate-resistant modified seed: okra, eggplant, mango, jackfruit. Some of my happiest memories are of tending the fruits and vegetables with him, in companionable silence. Tucking a seed into the earth, covering it up, drawing a circle with my finger around the little mound, the way he taught me. “My little farm girl,” he’d murmur.

But it’s not as if we spent all our time gardening. Next to the garden and orchard stood a small wooden cabin, not much more than a shed, and that’s where my father occupied himself most of the time, clacking out code on an old Coconut computer. It didn’t occur to me to wonder exactly what he was up to in there. I was a child. My father existed only in relation to my own small needs and wants.

He impressed upon me that he had moved to this remote island before my birth so no one would learn of my existence. If they knew the truth, it would be dangerous, given his stature. Someone could kidnap me for ransom. His political enemies on the mainland, having engineered his fall from grace, could now target me. He had reason to believe that some dangerous people up north on Bainbridge Island suspected my existence, though he wouldn’t elaborate. But these pronouncements never frightened me; I barely registered them. The idea of kidnapping, even the idea of people other than myself and my father — they were too abstract to be meaningful. Even he must have realized he couldn’t restrict me forever, because one morning when I was six, I begged him for the millionth time to let me venture past our little clearing into the forest, and, for no apparent reason at all, he laughed and relented.

I took off running.

All around our house stood dense stands of old-growth Douglas fir interspersed with cedars, maples, alders, and even the odd bit of non-native laurel and holly, planted a century earlier by the last family that lived on the island before us. This became my playground. Traipsing through sword ferns that rose to my shoulders, I imagined myself as the protagonist of grand, theatrical dramas, with the animals who inhabited the island as my supporting cast. I took the black-tailed deer under my protection as pets, pretending to guard them against predation. I cast the fat raccoons, who foraged for clams on the beach well past dawn, as my irritating little siblings. The enormous bald eagle who had built her nest in a Douglas fir near the beach and would spiral out over Puget Sound and back into the treetops again, was my aerial guard.

Hothouse Earth seemed abstract then. You remember. Being outdoors was still pleasant, the mornings and evenings cool even in the summertime. It’s true that in those days, the weather was already getting stranger, wildfire and hurricanes more common, the sunset slightly too beautiful, but the threat didn’t feel existential. Reasonable people still believed the planet could prevail over circumstance. Consider the gray whale, they said, thriving as the waters warm. Consider the bald eagle, back from obscurity. I believed it, too. One autumn, my eagle brought a mate home with her, and they spent a month building a nest, stick by stick. I spent that season standing watch, waiting for eaglets to be born. The world was still full of life. It was hard to believe it ever wouldn’t be.

One morning, I saw the eagle’s mate circle around the treetops for a while, and when he returned to the nest, a small beak popped up from inside to take whatever he had brought. I went running to my father’s office. He never minded interruptions, or if he did, he didn’t let on. I told him what had happened. “That’s wonderful!” he said. He swept me onto his lap, and I caught a glimpse of his screen, a steady march of code, like ants across the monitor. He kissed my forehead, my nose. But after a while, I could see his attention had returned to the screen. For such an intellectually curious man, my father didn’t have much interest in the life that teemed on our island: the mating patterns of the eagles; the way the underside of a sworn fern leaf could soothe the burn from a brush with stinging nettle; the licorice taste of the rhizomes that sprouted in the crotches of big-leafed maples; the sluggishness of the deer on hot afternoons; the raccoons’ practice of waddling right up to my feet to beg for scraps. What interested him was the theoretical. The way he saw it, the human mind was designed not merely to observe that which already exists but to invent that which doesn’t: to imagine a future and bring it into existence. He set me onto my feet again and shooed me off. “Okay, go explore!”

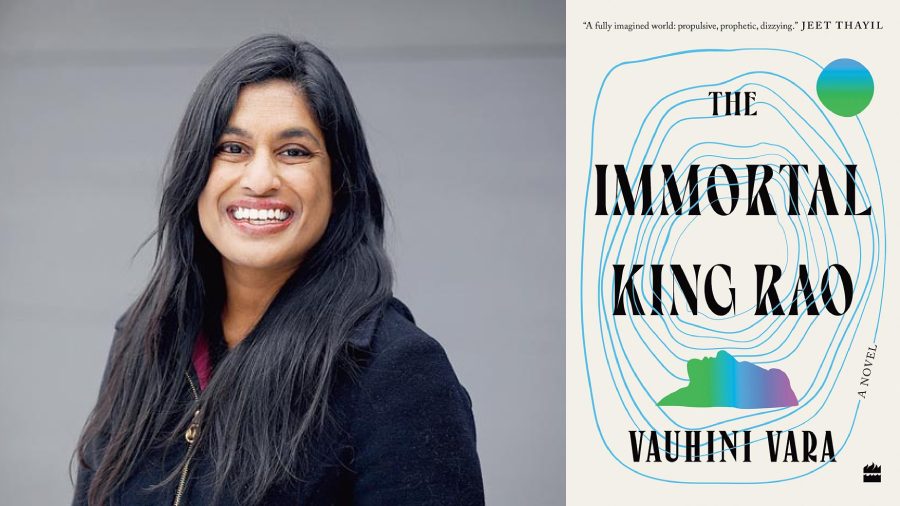

The book is being published on May 3 by HarperCollins India Publishers