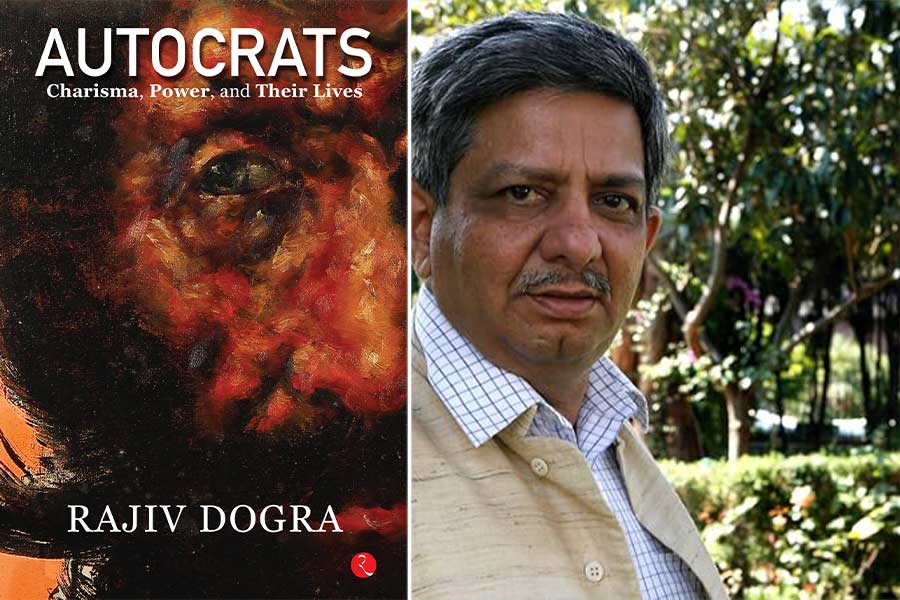

Once upon a time it was simple to answer the question, ‘what makes a dictator?’ However, in today’s time, things are more complicated, writes Rajiv Dogra in his new book Autocrats: Charisma, Power and Their Lives (Rupa Publications, 2024).

A former diplomat and a television commentator and artist, Dogra’s career in foreign service took him around the world. He served as India’s Ambassador to Italy, as the Permanent Representative to the United Nations agencies based in Rome, and was also Ambassador to Romania, Moldova, Albania, and the last Indian Consul General in Karachi, Pakistan. Today, he is a respected voice on foreign policy and the author of several books including Where Borders Bleed, India’s World, Wartime and Durand’s Curse, for which he won the VoW award for Best Book.

His latest book, Autocrats, delves into the lives, phobias, anxieties, demons and inner workings of the mind of authoritarian leaders. In the following excerpt, Dogra writes about the characteristics that describe a dictator in today’s world.

An excerpt from ‘Autocrats: Charisma, Power and Their Lives’

For our current discussion, the pressing question is: how do we describe a dictator in the current times?

Once, it was fairly simple to answer this question. The telltale signs included a love of uniforms, a propensity to harangue interminably, and a short fuse with critics, who were more likely to be done away with.

Now things are more complicated.

Can Jair Messias Bolsonaro, former President of Brazil, and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, President of Turkey, not be called dictatorial, asks Dogra Wikimedia Commons

For instance, is Viktor Orban of Hungary a dictator? Is Erdogan of Turkey one? Were Donald Trump as President of the US and Jair Messias Bolsonaro as President of Brazil not dictatorial while they were in office? Did they not whimsically discard democratic norms when it suited them? Were they not extreme when they directly or indirectly encouraged their supporters to rampage through their respective parliaments in defiance of the popular vote?

The follow-up question is: can all self-willed leaders be categorized as dictators? The answer to that is a clear no. It is not possible for anyone and everyone to be a dictator. The very first requirement is that a potential dictator must come

of age when the political system of his country is unstable.

It also requires a confluence of many other events to ensure his rise. First, a person must be born with the potential to develop brutal personality traits. These include narcissism, paranoia and an overwhelming desire for control. A potential dictator is likely to have grown up in difficult times and he could have suffered physical and psychological abuse in his childhood. His youth may have been marked by anti-social behaviour.

What are the other signs to look for in such a person? An early indicator is a dictator’s ability to inspire enthusiasm. Narcissistic leaders promise to achieve amazing results. They are great at presenting themselves and their ideas. Even more importantly, their speeches mesmerize people into believing that at last the messiah they were waiting for has arrived.

They know how to influence others. The methods may vary from one dictator to the other, but essentially they involve ingratiation, forming political alliances, horse trading and even threats. The dictatorial types are willing to make mistakes and take risks. They bounce back quickly from failure.

Besides these evident observations, the concept of ‘dark triad’ (it refers to a trio of negative personality traits—narcissism, Machiavellianism and psychopathy) has sometimes been used to explain a dictator’s mindset.

Among its characteristics, the first is narcissism, which was grossly evident in Trump.

Among the personality traits used to describe a dictator’s mindset is narcissism — a trait 'grossly evident' in Donald Trump, writes Dogra Wikimedia Commons

There is a dark side to narcissism. Despite outward bravado, deep down the narcissist is a nervous, insecure person because he knows he is not what he has made himself to be. As Freud pointed out, narcissists are emotionally isolated and highly distrustful. Perceived threats can trigger their rage, and achievements can feed the feelings of grandiosity.

Over time, however, this Freudian view has undergone some change. Now, psychiatrists acknowledge we are all somewhat narcissistic. However, there is a big difference in terms of the degree or extent of narcissism. In most of us, it is a microscopic challenge limited in scope and effect to the individual and to his immediate circle. The ill-effect of narcissism is limited to them, like their bad karma.

That is not how it works in the case of a dictator. With him the canvas is large; the entire country and its population is at his mercy. Therefore, the ordeal for a country is far greater. The challenge for the people is to ensure such leaders do not self-destruct or lead the country to disaster. This is neither easy nor always possible because it is very hard for narcissistic leaders to work through their issues—and virtually impossible for them to do it alone.

Narcissists need colleagues and even therapists if they hope to break free from their limitations. But because of their extreme independence and self-protectiveness, it is very difficult to get near them. This is the dilemma for a country that has a narcissistic authoritarian as its leader.

When such a person is riding high, at the very top of the country’s pyramid, who can dare suggest to him that he needs to consult a psychiatrist?

Yet, many of them need to. It will not be an exaggeration to assert that narcissism is normal among leaders. This must be so. Otherwise, they would not have the confidence to roughly elbow their way past others to reach the very top.

What then are the signs of extreme narcissism that border on personality disorder? It is difficult to make a definitive list, but if a leader has a majority of these characteristics, it should be taken as a sign of worry:

• belief that he or she is special and unique,

• lack of empathy for others,

• need for excessive admiration,

• obsessive sense of self-importance.

Nikita Khrushchev, a former premier of the erstwhile Soviet Union, thought Stalin was an example of this type. Accordingly, he denounced his predecessor’s penchant for promoting his personality cult as evidence of unhealthy egotism. In his famous Secret Speech of 1956, he alleged Stalin had even rewritten party history around his own biography.

It is too soon to fix a similar label on President Xi, yet his actions so far make him a perfect fit. He has centred all power in him, be it military, party or the executive. There is simply no one who can be considered as being within touching distance of the authority he has accumulated, and the myth of greatness that has been systematically built around him.

Xi’s narcissism has also extended the illusion of his grandeur beyond national shores. He seems convinced Western democracies are in decline and that the future lies with his model of authoritarian governance. He is also increasingly veering Chinese foreign policy towards grievance-based nationalism. Asserting control over the so-called lost territories of China is central to this agenda. So is dismantling existing institutions of global governance. In short, Xi wants to mould his country and the world outside to suit his grand ambition.

Read more about the book and buy it here