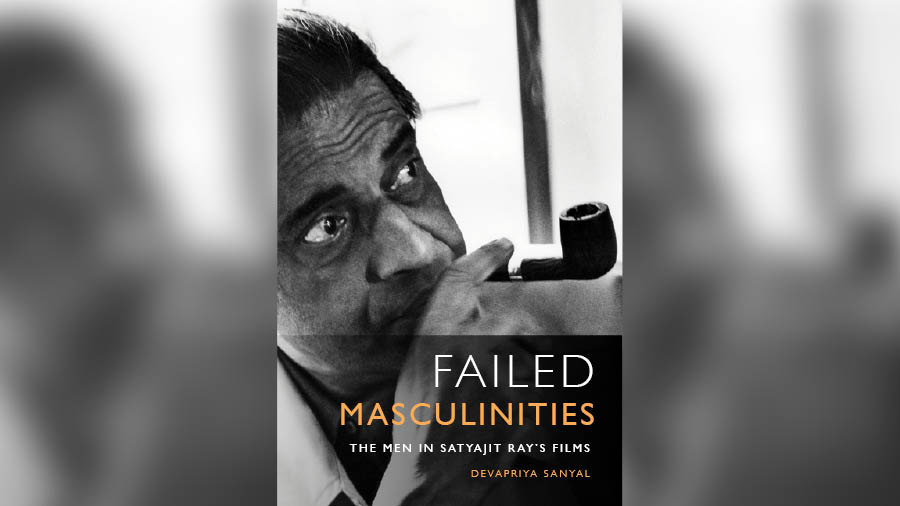

When Kolkata-born-and-raised Devapriya Sanyal is not teaching her undergraduate and postgraduate students at Mount Carmel College, Bangalore, she is writing, or watching world cinema. Her latest book Failed Masculinities: The Men in Satyajit Ray’s Films (Edinburgh University Press) is about Satyajit Ray’s cinema with a focus on his male characters.

My Kolkata shares an excerpt from Chapter 3, Breaking with the Past: The Apu Trilogy.

***

In Pather Panchali Harihar Roy, in failing to provide for his family, his wife having to become provider for the family, can be understood as the ‘failed masculinity’ of a people under colonisation. The crisis of masculinity variously noticed and described in Indian cinema provides enough evidence.

Harihar refuses to move with the times and would rather continue as tradition dictates and also follow caste hierarchy. We recollect a sequence in Pather Panchali when Harihar desists from giving diksha to a person with means entirely because he belongs to a lower caste. In one stroke Harihar’s personal ineffectuality – his refusing an opportunity to help himself when he needs money – is conjoined by Ray with the worst aspects of tradition, caste being its basis.

When Harihar is travelling and looking around for work, he forgets his family altogether, evidenced by the scarce mail they receive from him. It is also during his absence that Sarbojaya is forced to move into the role of the provider and takes to selling household utensils to keep hunger at bay. As we are told in the film, Harihar had previously left Sarbojaya in her paternal home for eight years after their marriage while he resided in Varanasi, and he has been habitually like this, someone whose masculine presence in the family is not comforting. The only activities we see Harihar engaging in are those of writing (he too has literary dreams and Apu inherited them), teaching Apu, eating the food cooked by Sarbojaya, doing ritual obeisance to the gods and later, in Aparajito, reading from the scriptures to the widows in Varanasi. But from the very beginning Sarbojaya is associated with doing the work in the household. Not only does she perform her womanly duties, but she also performs masculine ones: providing for the family when Harihar is away, pushing him to help fix the house, and providing money for Apu’s education.

Harihar is someone whose masculine presence in the family is not comforting

We could propose that since not becoming Harihar is a key desire in Apu’s construction of himself, he devotes himself to marriage with a vengeance, since that was where Harihar failed abysmally. When Aparna dies in childbirth, Apu is unable to bear the loss and throws away the completed manuscript of his novel. His son Kajal (whom Apu instinctively blames for Aparna’s death) is being brought up by Aparna’s parents and is growing wild, a factor brought to Apu’s notice by Pulu. Apu has been wandering about the country drifting from job to job, his unkempt beard becoming indicative of his inability to keep himself stable, but Pulu’s entreaty to take up his responsibilities as a father touches him; he consents.

It is customary for critics to see Apu’s loss of his wife sentimentally, but what is its true meaning in the context of the Trilogy as a whole? My own sense is that after having invested emotionally in his relationship with Aparna, her death shatters him so much that he begins to slip back into a Harihar-like condition. If the object of his responsibility is removed, what should he live for? His abandonment of his completed novel seems important, but that is autobiographical and deals with his own past, which he is only reflecting upon through it. Even unpublished, therefore, its purpose has been fulfilled – as an effort at self-understanding – and there is perhaps no need to go back to it. While Harihar dreamed of being a professional writer, Apu wants only to express himself – and perhaps exorcise the past. Although his novel was appreciated by Pulu, there is no indication that Apu wants to make something out of it. The positive ending in the film is therefore not Apu recovering the novel but manfully accepting the responsibilities that his own father had eluded.

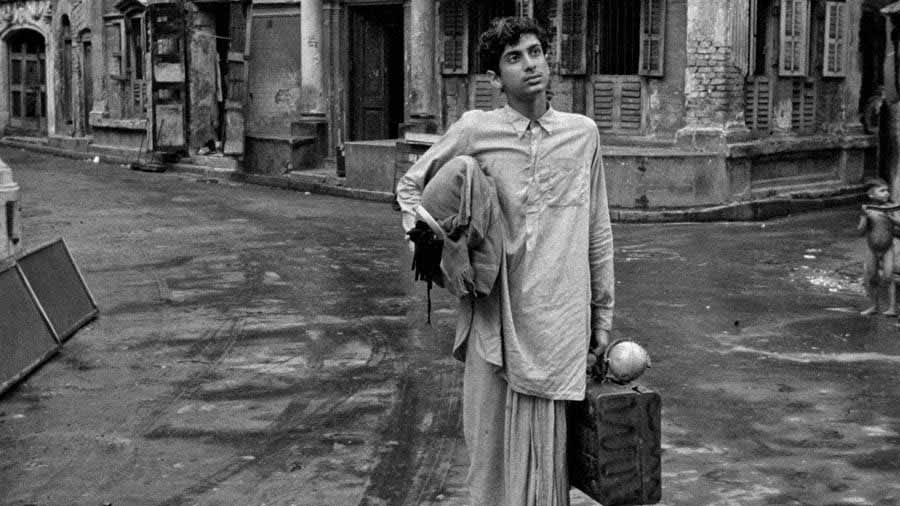

While Harihar dreamed of being a professional writer, Apu wants only to express himself – and perhaps exorcise the past. Seen here is a scene from ‘Aparajito’, where Smaran Ghosal played Apu

The Apu Trilogy is among the most important of Satyajit Ray’s works because it appears to be a statement on the independent nation, especially its agenda to break with an outmoded past and embrace modernity. We earlier regarded Apu’s eye as the key element in Pather Panchali, but Apu’s experience of his father has unconsciously imprinted itself upon him, and his endeavour as a family man is to move away from that. We do not see him paying much attention to Harihar in Pather Panchali, but the later films imply that impact. His efforts to be modern therefore also involve moving away from traditional modes of conduct, which is what Harihar represented to him.

Based on whatever has been said, The Apu Trilogy has more complex implications than simply being an allegory of the independent nation awakening to modernity. Apu also emerges from it as a psychologically distinct and complex individual, dealing with personal issues even as his presence and doings serve the ends of allegory. There are no public events named in the films to historicise the happenings, but there is an indication in the two later films that the period is India before 1947. The motif of a writer in fiction usually implies a milieu that has found its voice, and both the Hindi films named earlier were made in the 1950s, although Navrang was set in colonial India. The same is true of Apur Sansar, which merely anticipates a milieu that will find its voice with independence. But I would still argue that more important to the Trilogy than Apu becoming a writer is his accepting the responsibilities ahead of him, which would include mentoring a generation to make it fit for independence. Apu is not a ‘national subject’ since the nation is yet to be, but it is his responsibility to make his son Kajal one – when the nation does happen. This acceptance of his role perhaps makes Apu the most ‘masculine’ of all Satyajit Ray’s male protagonists.

***

Failed Masculinities: The Men in Satyajit Ray’s Films has been published by Edinburgh University Press and is available on Amazon here.

Devapriya Sanyal is the author of Through the Eyes of a Cinematographer: The Biography of Soumendu Roy (Harper Collins), Salman Khan: The Man, The Actor, The Legend (Bloomsbury, India), Gendered Modernity and Indian Cinema: The Women in Satyajit Ray’s Cinema (Routledge UK), and her latest release Failed Masculinities: The Men in Satyajit Ray’s Films (Edinburgh University Press).