Satyajit Ray had looked all over the city for his ‘Apu’. Only for his mother, Suprabha Devi, to discover him next door. Subir Bandyopadhyay goes back in time to recall his stint in the only film he acted in, including Ray coaxing his reluctant parents to allow him to act in Pather Panchali, and the taxi driver Bachchan Singh who ferried them to and from location in Boral…

It was perhaps 1951 or ’52. We were living in Lake Avenue. Satyajit Ray was our next-door neighbour – already a well-known name, a commercial artist in D.J. Keymer, son of Sukumar Ray. Of course, I was too small at the time to know all this. I only knew that the kakababu next door was a tall man – to look at him, one had to bend one’s head sufficiently backwards. One morning I was playing in the compound. Suddenly, someone from the house next door – perhaps their domestic help – smiled at me and said, ‘My boy, Dadababu is calling you.’ Who was Dadababu? I had no idea. Could it be a child lifter? Taken aback, I just ran to my mother. Mother came out and inquired why he was asking for me. The man said, ‘Dadababu wanted me to bring him. I don’t know why.’ My parents knew Satyajit Ray. They decided to let me go – not alone but with my elder brother.

Ray’s old house on Lake Temple Road, where he was next-door neighbour to his ‘Apu’ TT archives

I saw two beautiful ladies sitting there. Later, I learnt that the elderly lady was Suprabha Ray, Satyajit Ray’s mother. The other one was Bijoya Ray, his wife – I would come to call her kakima. Thakuma (Suprabha) kissed me and offered toffee to both of us. I was feeling a little nervous, but now all fears vanished. A little later, the huge, tall kakababu came in – the one I frequently saw from our verandah. Thakuma smiled and said, ‘Manik, you have been looking for Apu all over Kolkata. And here he is, next door, you never noticed! Look, I have brought your Apu.’

Bijoya Ray’s big contribution

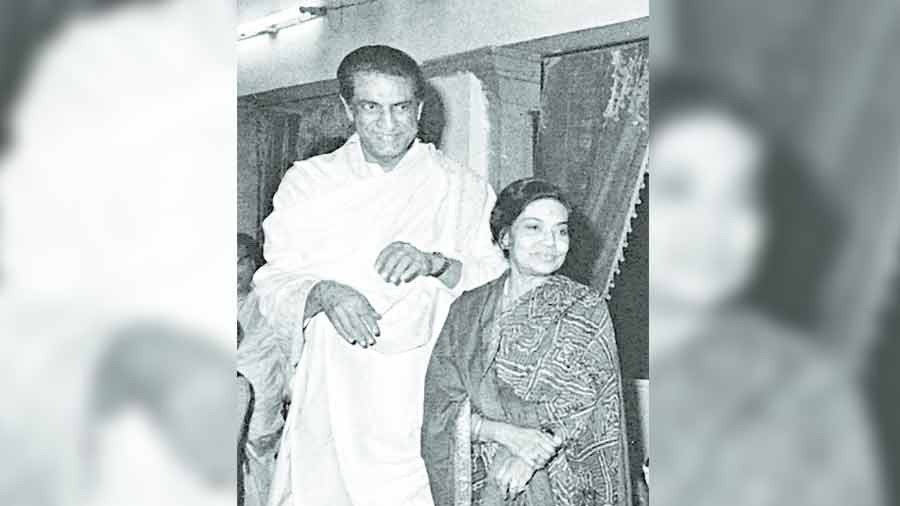

Kakababu looked at me for quite a while, turning me this way and that, the way a photographer observes his subjects. Then he asked me my name, which school and class I was in and all that. He said, ‘Come to the roof with me. I’ll take photographs of you both.’ Taking us to the rooftop he took photographs of both of us. (I have preserved that photograph taken by Satyajit Ray with me to this day.) We returned home thereafter. Later, I learnt that Kakima used to observe me playing in the verandah of our house. In a way, it was she who first thought of the possibility of casting me as Apu. She herself was a good actor and singer. Hers was no mean contribution behind the creation of Pather Panchali.

Satyajit and Bijoya Ray. ‘I learnt that Kakima used to observe me playing in the verandah of our house. In a way it was she who first thought of the possibility of casting me as Apu,’ Subir Bandyopadhyay said TT Archives

They picked me for Apu, but the real problem came now: convincing my parents. My father, Shantimay Bandyopadhyay, and mother, Jharna Bandyopadhyay, knew Satyajit Ray as a great artist. He was making a film, fine. But they could not think of letting their son act in the film. Acting in films was not as commonplace then as it is now. People in that era prioritised their children’s education and career – instead, here was a proposal for acting in a film! How could that be allowed? Even though father relented, it was difficult with mother.

Not taking no for an answer

As a last resort, mother took me to Giridih, to my maternal uncle’s place, during the puja holidays – in a sense, fled with me from Kolkata. She would never allow her son to act in a film. But to no avail. Satyajit Ray took our address from father and sent his production controller, Anil Chaudhuri, to Giridih to bring me back. And bring me back he did.

‘A day will come when the whole world will know us’

We returned to Kolkata. Then, one day, Kakababu came to our place and had a long conversation with my parents. I don’t know how he convinced them. But certain things that I learnt after growing up are still etched in my mind. Kakababu had said, ‘Why are you hesitant to allow your son to act in a film? It’s taken me so long to find my Apu. I have seen over two hundred boys, but couldn’t find any. The film won’t be possible without him.’ Then he said something that my parents could not disregard. He said, ‘I’ll make a film that will alter the course of Bengali film-making. Today no one knows your son or me. But a day will come when the whole world will know us.’ Imagine the self-confidence and far-sightedness a director must have to say something like this even before starting work on his first film.

Discovering new meanings

So much has been written about Pather Panchali; so many debates, so many screenings. Even today, the film enthralls the audience, stirs them as it did 60 years ago. Kakababu presented beautifully the intimate relation between man and nature that Bibhutibhushan wrote about. I was not old enough at the time to appreciate all these. Nor was I supposed to. I have since then watched the film so many times – and each time I am overwhelmed with newer joys, I discover newer meanings.

‘Kakababu presented beautifully the intimate relation between man and nature that Bibhutibhushan wrote about’

Take the scene where Harihar returns home with a sari for Durga. The house has been devastated, Durga is dead. In this scene, Kakababu does not show only Harihar and Sarbajaya. The camera pans over the entire house, destroyed by nature’s fury. The fallen house and Durga’s death merge. As if the natural storm is a harbinger of the storm that befalls this small, poor family. It is as if the struggle of all the deprived people of the world, their hopes and desires, are manifested in this scene. That is why Pather Panchali is ageless. That is why it is prized as a ‘great human document’. That is why even after 60 years we can undoubtedly say, Pather Panchali was, still is, and will remain. The appeal of Pather Panchali is eternal.

Harihar returns home with a sari for Durga in this scene from ‘Pather Panchali’. The camera pans over the entire house, destroyed by nature’s fury. The fallen house and Durga’s death merge. As if the natural storm is a harbinger of the storm that befalls this small, poor family Government of West Bengal

Let me say a few words about the shooting. I felt as if we were going on a picnic. There was no fear or anxiety. It was all pure joy. There used to be gaslight in Kolkata streets those days. And large taxis – Studebakers, etc. There was a Sikh driver – I still remember his name – Bachchan Singh. Every morning we used to take the car to Boral and return by evening. Not that we had to work the whole day. Monkeys were a nuisance. Once, they threw green coconuts on our car, denting its hood. I remember, I was never served outside food, lest I fall sick. Kakima used to carry specially prepared food me. It was a homely atmosphere. I was so small that I do not remember everything well. I didn’t even realise what a classic film I was being part of. The shooting went on for three years, interrupted now and then for want of funds.

‘I never felt like acting in another film ever’

I was nine when the film released on 26 August 1955. Later, I received many more offers for acting in films. But my parents did not agree. I feel proud of having been associated with the timeless work – Pather Panchali – which remains my only film. Even after the lapse of half a century, I get an occasional invite to some function or am asked to write a piece for a newspapers or journal, only because of this one film. I feel proud of myself. I have received such fame and love that I never felt like acting in another film ever. I just want to live with the identity of that eternal ‘Apu’.

Parambrata Chatterjee as Subir Bandyopadhyay in 2013’s ‘Apur Panchali’ SVF

Extracted from an essay originally published in Bengali in Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali, edited by Arun Sen, Kolkata: Pratikhkhan, 2005.