This has been Durga Puja week, celebrating the time when Durga, the wife of Shiva, returns to her mother’s house for four days after she has been married, and then goes away again with Shiva. A week before Durga Puja she is summoned to Calcutta by the sunrise ceremony of chants and songs that I heard at Shantiniketan, and then she comes a week later. All over the city, in crèches made of banners, there are images of Durga, with ten arms, slaying the buffalo demon who represents the miseries of the world. The story goes that after she slew him, she was so impassioned that she went on destroying everything, finally even stepping upon Shiva and opening her mouth to swallow him up too. But then she realized what she was doing and became pacified. She is usually depicted stepping on Shiva with her tongue out; since sticking out the tongue is indicative of surprise in Bengal, one Bengali I spoke to said that she sticks out her tongue because she suddenly realizes, ‘Argh! I’m stepping on my husband!’ Others maintain that all women walk all over their husbands, and she is merely sticking out her tongue to taunt him. This story is the complement to the one in which Shiva is about to destroy the world, and his wife pacifies him; it comes to the same thing in Hindu cosmology, where the male and female principles must be united to keep the world in balance, and to create.

The images of Durga are worshipped by beating steel drums in front of them constantly for four days, and it really begins to drive you out of your mind after a while. Yesterday, early in the morning, a goat was sacrificed to Durga, and I got up and walked through the still dark streets to the place where a family was sacrificing its own goat. As the drums began to get louder, the people who were sleeping all over the street began to wake up and walk towards the shrine; the noise became deafening as the boys began to blow on the conch shells and strike metal pots together. The priest sprinkled Ganges water on the goat and talked to him, telling him, as in the Rig Veda, ‘Don’t be afraid, goat. You are going the good going,’† but the little goat wasn’t having any. Bleating, he was carried to the sacrificial block, and a string was tied around his head. The priest pulled on his head, and two men pulled on his feet, stretching him out taut. The sword was offered to Durga to be blessed, and then with one stroke the head was severed from the body, and as it sprang free the priest held it high in the air and carried the head to Durga as an offering. Then the drums stopped, and after reciting a few prayers, the people went away, and I decided I wanted a breath of fresh air.

Later I went to the great temple at Kalighat, and there was a tremendous crowd of people bringing baskets of offerings on their heads, filing past the great image and leaving the offerings. Within the temple there were hundreds of goats waiting to be killed, and there was a great pile of heads in one corner, while in another the dogs were eating the skin and offal. All the beggars in India seemed to be there, and shops selling sweets and garlands and images of the goddess, and people shouting as they poured into the temple, and the bleating of the goats and the chanting of hymns. It was deeply disturbing in a way that the simple sacrifice at dawn had not been. There was a violence and misery about it that I had never imagined before. And right after that I went to the Indian Museum to see the fabulous gem-encrusted statues of the medieval gods, and the serene dancing Shivas, and the contrast was overwhelming. The art in the museum was produced by people worshipping a different kind of a god, perhaps in a different part of the land, in a place of peace and beauty, where a gentle life inspired the worship of a gentle god*—but even then there were terrible, terrible stories of the cruelty of the gods that make Job seem blessed, and these

stories were told of the same majestic, serene Shiva that I have always loved. I can’t sort it out in my mind; I know that it all goes together, but emotionally it seems impossible to reconcile.

Then the images were all dismantled after the fourth day and taken down and thrown into the Ganges. Everyone was drunk, and as each image came by (there are about five thousand of them, each tremendous and intricately carved and decorated, covered with real garlands and necklaces, each goddess standing on a life-sized, fuzzy lion and killing a half-demon half-buffalo) on bamboo poles on the shoulders of some twenty-five men, it was preceded by a band, the most wonderful music I’ve ever heard, consisting of flutes, steel drums, skin drums, pipes, bagpipes, brass pots, and conch shells. The rhythm is a combination of the Indian tunes, with their five- or seven-beat syncopation, and the steady beat of a kind of jungle rhythm, and a real jazzy off-beat, and a calypso lilt, and the tune is equally lively and mixed up. All the children carry candles and dance around, really dance, and shout and it’s altogether the most fun imaginable. Then, at midnight, we went down to the Ganges and sat by one of the ghats; the river was lit by candles and lights all up and down the bank, and there were thousands of little pole-driven boats floating up and down, lit with candles and overflowing with people. One after another they heaved the great images into the river and dived in after them, shouting and pushing them under the water, then splashing the holy water on everyone, and making way for the next image, and all the time the drums and flutes were playing, and people singing.

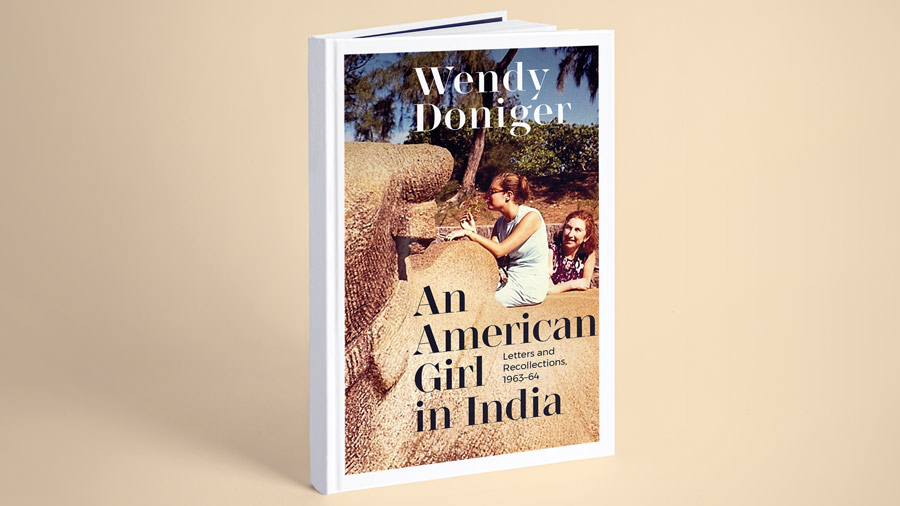

An American Girl in India: Letters and Recollections 1963–64 by Wendy Doniger has been published by Speaking Tiger in 2022.

Read more about the book here: speakingtigerbooks.com