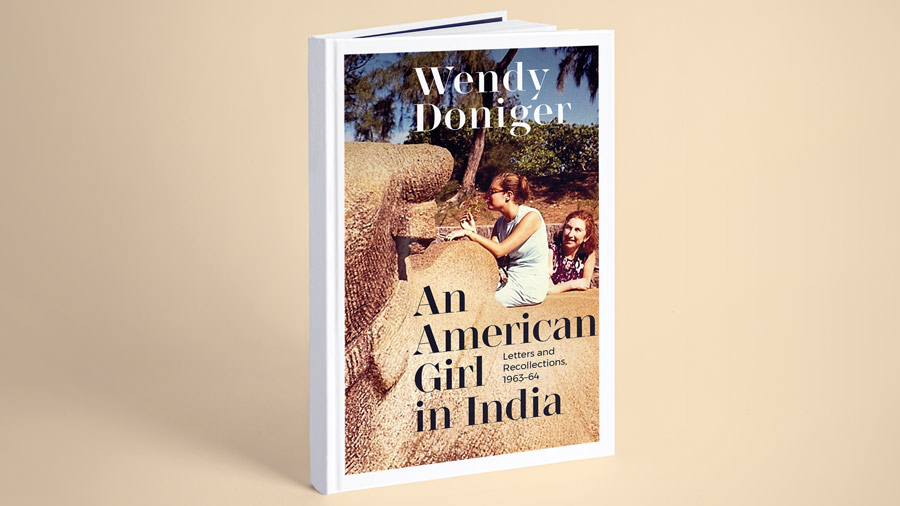

Wendy Doniger writes in the preface to her recollections – “In August of 1963, when I was twenty-two, just one year past my graduation from Radcliffe College, I landed in what was then called Calcutta (now called Kolkata) on my first trip to India. I had a year’s grant to study Sanskrit and Bangla (which we then called Bengali), the language of Bengal.

Fast forward. In January of 2019, when I was seventy eight and had just retired after forty years of teaching at the University of Chicago, I was clearing out my office in the Divinity School and came upon a box of letters tucked away behind a cabinet. I opened one of the letters and read, ‘Calcutta, December 10, 1963. Dear Mommy and Daddy, …’ These letters, typed on the trusty little Hermes typewriter that I carried with me everywhere in those days, had apparently been saved by my mother and must have come back to me on the tidal wave of books and papers that overwhelmed me when she died in 1991. Now, in my office, almost thirty years after I received them, and almost sixty years after I had written them, I opened the box.

This book is an annotated edition of those parts of these thirty-three long letters that discuss my experiences in and thoughts about India at that time.”

The following excerpt captures the events of August 17, 1963.

=====================

Having managed to get myself and all my luggage on the right train (a tale full of sound and fury), I arrived at Bolpur (the sign on the station spelled it Bolepur, the post office spells it Bolpure, the people at the University spell it Bolpur—life is very approximate here) after having had tea served on the train. There being no corridors but rather compartments, English style, the man serving the tea had to actually scramble along the [out]side of the moving train, holding on to windows and handles, all the while balancing a tray in one hand, like a scene from a Harold Lloyd movie, and dashing into the compartment just in time to avoid being squashed against a tunnel we were entering, while the engineer blew the whistle loudly, as he did in every tunnel, like the children at the zoo.

Arriving at Bolpur in the evening, I was met by a delegation from Shantiniketan (everyone had warned me that when I arrived at Shantiniketan no one would have heard of me, and I would probably have to sleep in the street: this was diametrically opposed to the true case, as you will see. I heard all sorts of untrue rumours about Shantiniketan while I was in Calcutta. It is a place of great controversy, because the Bengalis are great hero-worshippers, and Shantiniketan is a shrine to Tagore, and the Bengalis are also great iconoclasts, so opinion differs widely. You will soon see which class I fall into) consisting of a girl from Trinidad and a girl from Thailand. They put me and my bags into a kind of rickshaw pulled by a boy on a bicycle, the only means of transportation out here besides bullock, and told me that everyone had been waiting for me to come for two weeks already, and that my room was all ready and everyone dying to meet me. And it has been that way ever since. As I began to type this page, Yubon, the Thai girl (pronounced ‘tiger’, much to my confusion at first) who lives next door, brought me a bowl of lotuses and asked me how to pronounce ‘luxurious’; Chat Su, who is also Thai, gave me a special Thai sauce to put on my rice. The night I arrived, I was unpacked, mosquito netted (you drape a sort of canopy over the bed, giving a lovely, airy, safe feeling, like being in a crib, or sleeping in the summer palace of a king; I have always loved to crawl under things and go to sleep), briefed, questioned, admired, all in a great flurry of girlish curiosity.

I live in the Scholars’ Block, Birla Hostel (room 16, for the mail boy), where most of the foreign (that is, non Bengali) girls live, Chinese, Punjabi, Trinidadian, Persian, South Indian, and Japanese. I am the only American here. Being foreigners, we have many special concessions: we live in the newest hostel (five months old), have showers and toilets and good, soft American-style toilet paper, don’t have to play games (which is a damn good thing, as they are held at 5 every morning: as it is I get up at 6, but am already accustomed to it). Classes are from 7 to 11 and from 2 to 6, to avoid the hot part of the day. I have only two classes, Bengali and music (that is singing and dancing), but I rise with the others to go to morning prayers, when we stand in the forest and sing the ancient and, I have discovered, beautiful hymn, ‘Om, Shanti, Shanti, Shanti’. I am also learning Tagore songs. But I digress.

I made an immediate friend of a girl from South India, who is studying painting here and to do so has had to be away from her husband, who lives in Delhi, where she visits him over vacation. She loves him very much, and misses him, and I told her all about how I met my fiancé, and she told me all about how she met her husband, and I suddenly realized that she had met him at her wedding, of course, and yet our feelings were so very much the same. She was married a year ago and came here only two months later; the girls call her Bhabhi, sister-in-law, and tease her, and she blushes furiously. I am not yet teased, but I am told that my boyfriend looks very big and strong, a remark which is followed by wild shrieks of laughter and a babble of multilingual comments. It is, of course, a girls’ dormitory, an institution from which I have been known to go to the most extreme measures to escape, but it is more than saved for me because the girls are all extremely innocent and bright and happy and generous and friendly and, though they seem much younger than Americans of the same age, dignified, and dignity is the one quality which makes it possible to live close to people. Some of them do speak English quite well, and when they do it is none of the malicious, small, spoiled, and usually quite obscene gossiping that so characterized my alma mater, but talk of their countries, and their studies, and what they hope for in life, and things that strike them as funny, and all the things I like to talk about. I was also quite pleasantly surprised to find that they are all crazy about America and Americans: I expected to be a dirty word in India, but not so. A lot of it is, of course, material: ‘Some Thai things are good,’ Yubon agreed when I admired her dress, ‘but all American things are good.’ But it’s more than that. It would seem that Americans have been more friendly and interested and generous and accommodating than the other non-Indians they have met; perhaps I will be able to find out more about it, but for the time being I’m not going to look a gift horse in the mouth.

Wendy Doniger Wikimedia Commons

Things here are very simple and beautiful. I have put away all my good dresses and wear only one or two rayon ones. When the rains stop, I will wear saris and Punjabi dress (pants and a long tunic with a chiffon drape at the shoulder). Dinner is served in a cool hall with long wooden benches and metal plates and cups. My room has a bed with a bright orange spread and white netting canopy, a large cabinet for my clothes and toilet articles, which is metal and locks, a desk with a brass vase filled with peacock feathers, books in a pair of sandalwood bookends, a sandalwood frame for photographs, a bowl of lotuses, replenished with a different colour lotus cluster every day, a chair, and that’s about it. At night, the bearer comes in with a stove of incense that drives out the insects while I am out, and then I burn punk, good old punk, which takes care of them while I am asleep. There are a great many insects of unbelievable dimensions, and the lizards grow long and fat on them. Only now can I fully appreciate the sacrifice made by the Jains in wearing gauze masks to keep from destroying any insects: loving these insects really takes a lot of doing.

In the evening, the girls in the Sangeet Bhavan [‘Song Block’] ([there was a sign that read:] ‘Except in the Sangeet Bhavan, music and dancing is forbidden during study hours’) sing and play the sitar. Everywhere girls are painting in the classical style, some copying famous miniatures, some sketching the cranes down at the lake. There are beautiful, strange trees and flowers outside my window, and exquisite birds and funny little cat-like goats, and skinny cows with soft eyes, not like our cows at all, and at night the jackals howl for about an hour, an indescribable sound like a cross between the yowl of a tomcat and the baying of a hound and the mooing of a frightened cow. And, much to my pleasant surprise, the afternoons are filled with the sounds of children. Shantiniketan is really a little colony and teaches kindergarten as well as graduate school; there is no school in the afternoon, and so there is a lot of scurrying and singing and crying and screaming and chanting and falling down, and all the sounds that I most like to hear outside my window when I am pretending to work. At night, there are so many stars that it would be easier to count the patches of blue than to count them. The Milky Way is like a great white chiffon scarf, or, as the Indians used to believe, like the Ganges flowing through heaven on its way to earth. I counted a hundred shooting stars from my window last night, in just a few minutes. It is quite cool at night, with breezes, and everyone makes tea for everyone else.

An American Girl in India: Letters and Recollections 1963–64 by Wendy Doniger has been published by Speaking Tiger in 2022.

Read more about the book here: speakingtigerbooks.com