If it’s Puja, saris are a must buy, and perhaps the most coveted sari weave is the Jamdani.

My Kolkata travelled all the way to Phulia — the sari hub of Bengal — to meet master weaver Biren Kumar Basak and decode what makes Jamdani the queen of all saris.

Excerpts from a chat that touched upon all things sari — the weaves of Bengal, the evolving textures of saris over the years, handmade vs machine-made saris and more…

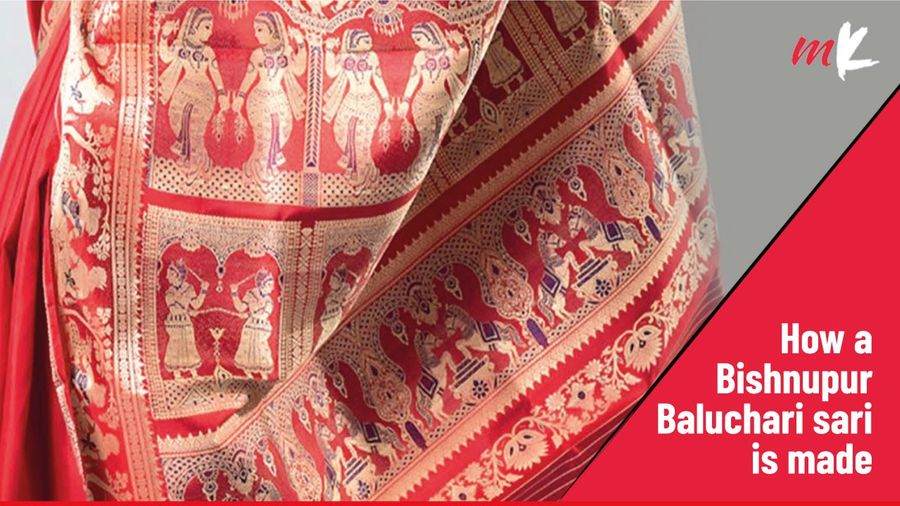

What is Jamdani?

Jamdani is a very traditional sari that is woven on a handloom. Though a lot of power loom, or rather machine-made, Jamdanis are now readily available in the market, the authentic Jamdani is always handwoven. Jamdani weaves require special skills. Jamdani weavers are always in high demand for their skills.

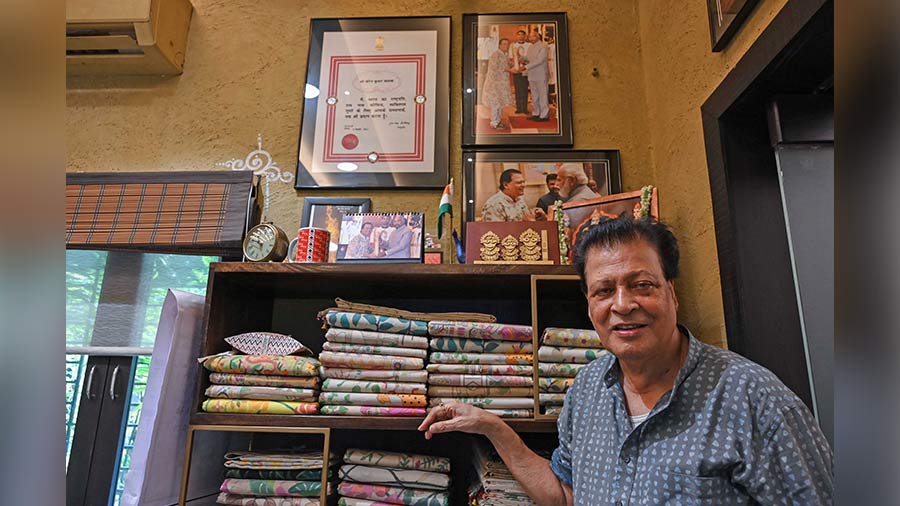

Biren Kumar Basak, a master weaver of Jamdani and Tangail saris, started weaving Jamdani on natural cotton, khadi muslin, khadi, muga and other textiles. His designs are intricate and he uses both traditional motifs like Ganesh, Durga or stories from the Ramayan as well as non-traditional ones.

Biren Kumar Basak took around two-and-a-half years to complete the Ramayan sari

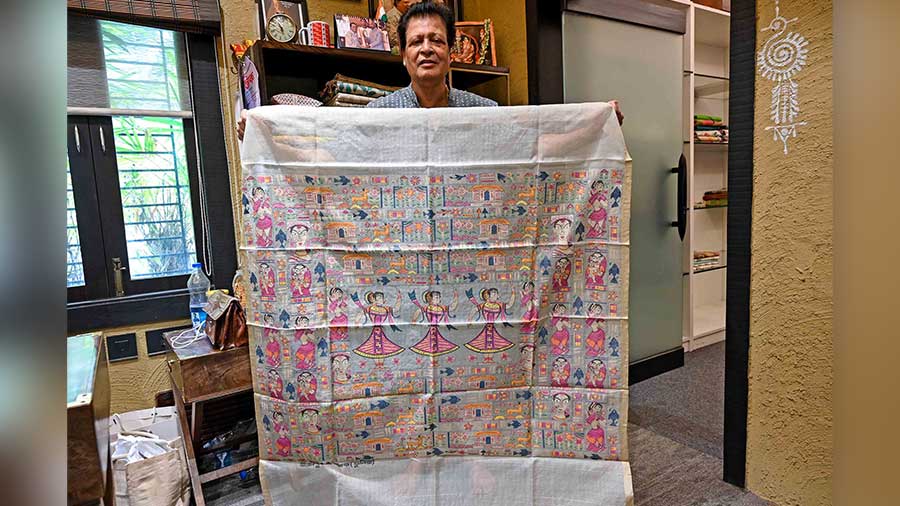

Basak’s saris are distinct from the traditional taant Jamdani. They depict epics, stories about tribal culture, nature and more.

His saris tell stories and this art of storytelling fetched him the Padma Shri. He is also known for his intricately woven Jamdani wall hangings.

A Jamdani wall hanging

The making of a Jamdani

The difference between machine-made and handwoven Jamdanis can be understood by studying both sides of the sari. In a handwoven Jamdani, the weaving is double-sided leaving no loose ends that need to be cut on the inside. If the inside of a sari has cut ends, then it’s machine-made. It needs a trained eye to distinguish between a handwoven jamdani from a machine-made one.

Weaving a Jamdani by hand can take anything between two days to several months to and the price of a sari can go up to lakhs. Biren Kumar Basak’s famous Ramayan sari took around two-and-a-half years of work. Jamdani work is now done on different materials such as cotton, muslin and matka. The motifs vary from simple to intricate.

Weavers of Jamdani saris earn Rs 8,000 to 10,000 a month on an average.

A loom at work

The beginning

Basak learnt the art of weaving from his father Banko Bihari Basak. Born in 1951 in Tangail district in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), Biren Kumar Basak started weaving saris from the age of eight years. By the time he was 12, Biren Kumar Basak had started to weave Tangail saris with traditional borders.

“Tangail is a district in Bangladesh, where these saris were originally made. There was a haat there in Bajidpur, where people would go to buy saris. Even people from India would go there,” Basak said.

A motif is being woven in a sari by hand. Needle work is the most popular method in weaving Jamdani motifs by hand

Basak migrated to India in the 1960s and came to Phulia, where some weavers had already set up home. “Since I knew how to weave, I started weaving saris immediately. I would get Rs 5 for weaving a pair of saris,” he said.

Biren Kumar Basak and his brother Dhiren Kumar Basak would travel to Kolkata from Phulia, carrying with them a pile of saris.

The hard work soon paid off and Biren Kumar Basak’s saris were in demand among discerning buyers.

From only cutting threads to weaving on the loom, women have found a stronghold in the cottage industry of weaving

Master trainer and pioneer

It was around 1962 that Biren Kumar Basak started to work with weavers. He even encouraged women to weave — this was a revolution of sorts as weaving was, at that time, considered a male domain. Women were only allowed to cut threads.

Biren Kumar Basak trained women to use the loom. Today, around 3,000 of the 5,000 weavers who work with him are women.

He has also been a pioneer in changing the character of the traditional Tangail. “The traditional Tangail sari meant a plain sari with a paar (border). Then slowly motifs started getting introduced and I also started making Jamdani motifs on Tangail.’ These saris were never made in Bangladesh’s Tangail. It is here in Phulia that Biren Kumar Basak started weaving a new kind of Tangail sari while retaining traditional motifs such as lotus, grapevine or fish skin patterns.

Evolution of Bengal’s saris

West Bengal has a rich heritage of saris — be it Shantipuri, Dhaniakhali or Tangail. These were all starched cotton saris but it is this character of the Bengal cotton that led to a drop in its popularity among a younger generation that was not used to saris.

Weavers innovated and started using khadi thread to make the saris soft and Bengal saris regained popularity.