The Baluchari’s legacy is one of resilience. The heritage weave has been preserved by a steadfast community of weavers for centuries, the secrets of its craft passed on from one generation to the next to save it from oblivion.

The Baluchari silk sari received a GI tag in 2012 and boasts a unique design heritage. In the last few years, homegrown labels have woken up to the uniqueness of this handloom weave, which has been around for centuries. But despite its revival, the craft faces new challenges in the post-pandemic market.

Back to roots

Though Bishnupur is presently the largest producer of Baluchari saris, it was first woven in a place named Baluchar in Murshidabad. The then-Nawab of Bengal, Murshid Quli Khan, brought the weaving tradition all the way from Bangladesh in the 18th century. He helped establish a weaving community in Baluchar village in Murshidabad, on the banks of the Bhagirathi river.

However, with the advent of the British Raj, the nawabi patronage dwindled and the production of Balucharis experienced roadblocks. Moreover, the community soon had to relocate to Bishnupur after Baluchar was submerged in a flood. It is from Bishnupur that the Baluchari started regaining its lost fame, around the first half of the 20th century.

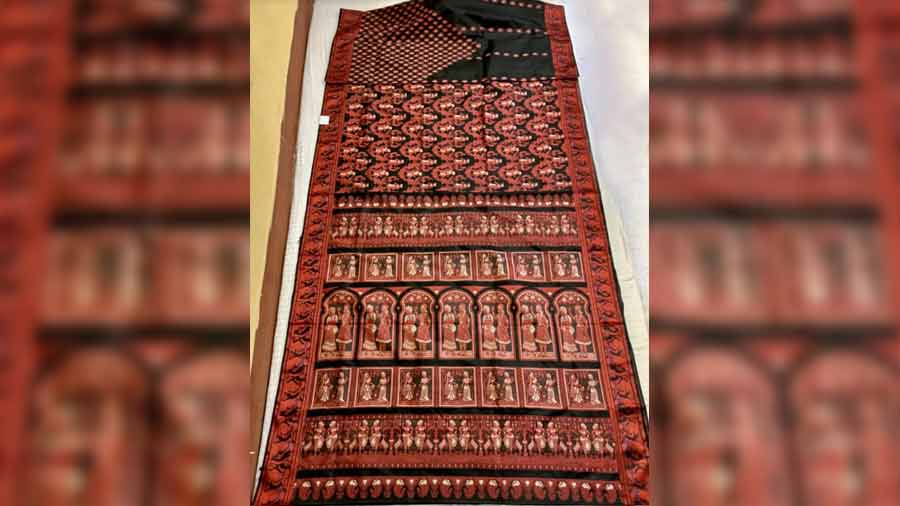

A Baluchari woven in Bishnupur Courtesy: Kaniska

Acclaimed artist Subho Thakur and master weaver Akshay Kumar Das had much to do with the revival of this magnificent weave that was on the verge of obscurity. Hanuman Das and his son Bhagaban Das, of Bishnupur’s Silk Khadi Seva Mondal, provided moral and financial support to restore the rich tradition of this craft.

Initially, Baluchari saris would feature pictorial depictions of nawabi life — be it nawabs riding horse carriages or bibis smoking hookahs. Colourful, large mangos and paisley motifs surrounded with small box patterns were prevalent on these weaves.

Gradually, stories of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata found their place in the designs of the Baluchari. Motifs like palkis, the exiled Pandavas and the santhal patterns were woven on the pallus. By the late 21st century, this heirloom product had acquired cult status and by the ’90s, nearly 1,200 looms were operating in Bishnupur to cater to the demand.

Stories of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata have found their place in the designs of the Baluchari TT archives

However, this growth curve saw a steep decline in the early 2000s due to the high cost of production and the number of looms came down to 400 by 2004-05. This forced the weavers to start looking for other means of livelihood. But then, from around 2010, with some government intervention, things have picked up again.

Weaves of change

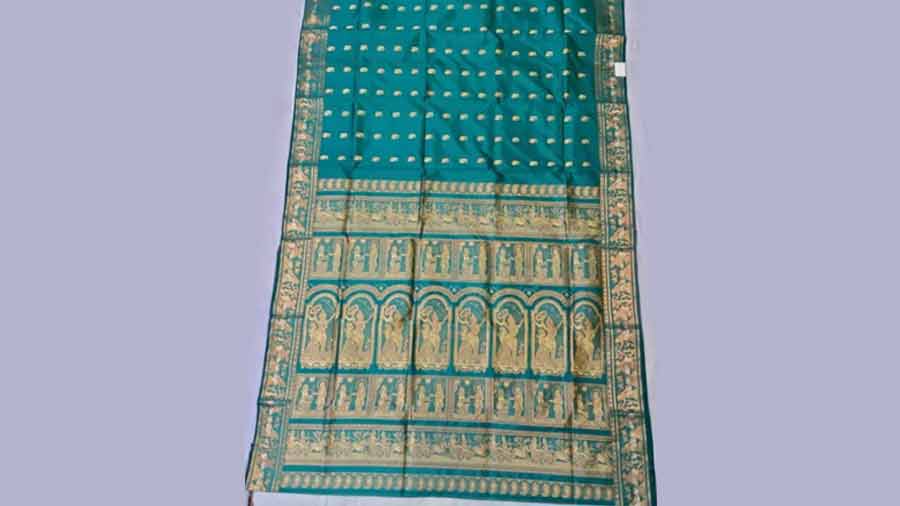

Baluchari saris mainly come in three kinds of patterns. The single-coloured silks are made with single-coloured threads, the meenakari ones are woven with a number of coloured threads and the swarnachari features motifs woven with golden or silver threads. The Swarnachuri was first woven around 1989-90 and at the beginning, it was only woven on black and white silks. Eventually, it started being woven in different colours and saw a demand in the Bengali wedding trousseau.

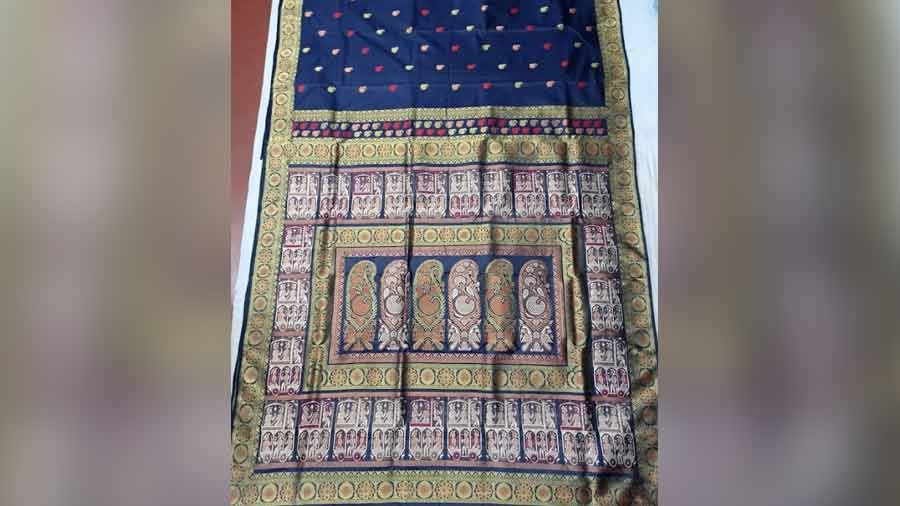

Presently, revival Baluchari saris with Mughal motifs are experiencing a surge in demand. In Bishnupur, four looms are used presently to produce the revival Baluchari saris. The process of weaving a single sari may take anything from 15 days to a month, and they naturally come with a higher price tag.

Swarnachuri saris usually use gold or silver threads Courtesy: Kaniska

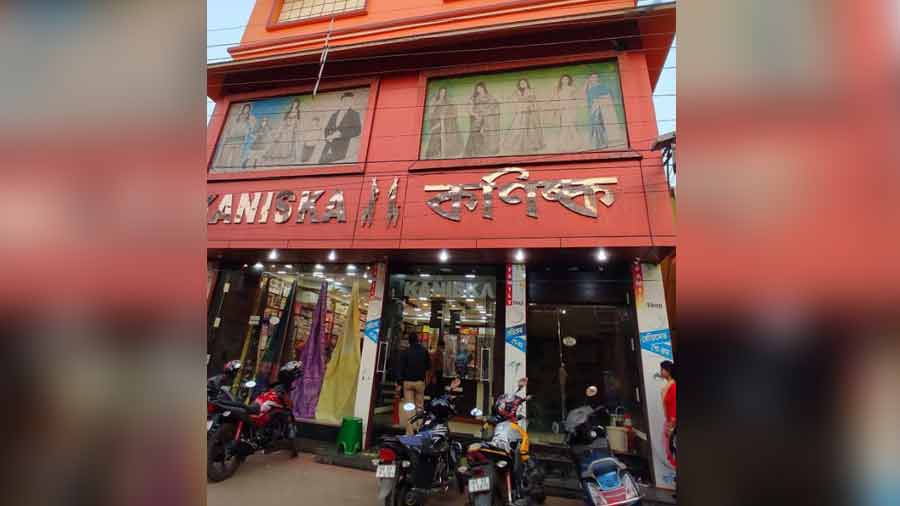

The label Kaniska is one of the most popular producers of Balucharis in Bishnupur. Located in Lalbag, this shop has established a steady virtual presence for global buyers. “Online shopping has actually helped the handloom industry immensely, especially during the Covid period. People started to buy a lot of saris during the lockdown period, which in a way helped the industry,” says Phalguni Das, who owns Kaniska.

Kaniska in Bishnupur has a steady online clientele Courtesy: Kaniska

Das has been associated with the weaving and trading of Baluchari saris for decades. His grandfather owned Kabiraj-er kaporer dokan, a Bishnupur shop famous for their selection of Balucharis. The other two noteworthy outlets are Silk Khadi Seva Mandal and Mallabhum Silk Centre.

Das learnt the secrets of the trade from his grandfather. Since then, he has been closely associated with the weavers of Bishnupur and has also identified the day-to-day challenges. The jacquard machines that are used to make the saris, he tells us, pose a problem. The machines are so heavy that older weavers find it difficult to use, in spite of being skilled in the core art.

The designs that we see on the saris are first drawn on a graph paper. Then, they are drawn and punched into cards known as punch cards. Then the cards are sewn following the design and then fixed in the jacquard machine, before being punched into the saris. This process requires a lot of skill. Though newer machines are available now and can help with streamlined production, the installation is expensive.

A revival meenakari Baluchari Courtesy: Kaniska

Das also points out that if the next generation of weavers start pursuing other professions, this craft will soon dwindle. He mentions that since the pandemic, fewer cocoons have been cultivated, which has led to a dearth of threads. As a result, the cost of threads has increased by leaps and bounds, affecting the market price of the Balucharis. This gap in demand and supply is a big factor behind the price hike and needs to be addressed, he says.

But there’s hope still. The new generation of weavers is troubleshooting its way out of a crisis. They are updating some of the designs to fit current sartorial needs, so this heirloom weave can keep up with a modern market.