Gabriel Jose García Márquez died of pneumonia on April 17, 2014, in Mexico City, Mexico. He was 87 years old. Eight years later we now know that he left his burgeoning global readership an unexpected inheritance. The world publishing industry, especially the Latin countries and the US, are doing nothing short of a happy dance that a posthumously published novel will soon belong to the planet’s reading public.

Marquez had published a short story titled En Agosto Nos Vemos, which translates to See You In August, and might have been working on a novel version of the same. Marquez’s manuscripts, which I visited in 2007, are mostly archived at the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin. On wanting access to this shrine while I was writing this article, I found that this particular manuscript is not available for viewing. In the literary firmament, this is top secret, since news of the publication of its avatar as a book or novel is currently at fever pitch. The 150-page book will be published by Penguin Random House and is expected to stir up a storm on its birthing.

Not one to give up easily on an author who has been an inspiration with his whacky sense of the world and his unique ability to see the comic in the most disastrous of events, I did ferret out a Spanish version of the original short story, and then acquired a translation of the story of See You In August. This, I realised, is a brilliant story and I wanted to share it with our readers.

To the best of my research, there has not been any unveiling of this particular short story in the press. So, I have provided a gist for those of us who might find a whole year too long a wait. Ever since the author passed away eight years ago, rumours were rife about the possible publication of a book on this short story, which Marquez had published in 1999 in the Colombian magazine Cambio and it was supposed to be the first chapter of the unpublished manuscript.

Márquez, widely known as ‘Gabo’, was born in Aracataca, Colombia, on March 6, 1927. He was the eldest of 11 children to Gabriel Eligio García and Luisa Santiaga Márquez Iguarán de García, though he was raised through his childhood years by his maternal grandparents, Colonel Nicolás Ricardo Márquez Mejía and Tranquilina Iguarán Cotes de Márquez.

He graduated from the National College for Boys in Zipaquirá, a small colonial city outside Bogotá, in 1946 and then enrolled at the National University of Colombia in Bogotá to study law before transferring to the University of Cartagena.

The rest is history: García Márquez left his law studies to become a journalist and a writer. He wrote for several Colombian newspapers in the early 1950s including El Universal, El Heraldo, and El Espectador, and his first novel, La Hojarasca (The Leaf Storm), was published in 1955. From 1955 to 1957, he lived in Europe, working first as a foreign correspondent and then as a freelance journalist based in Paris.

He also wrote two novels during that time, published several years later as El Coronel No Tiene Quien Le Escriba (No One Writes to the Colonel, 1961), and La Mala Hora (In Evil Hour, 1962). The town of Aracataca, where Gabo spent most of his childhood in the home of his maternal grandparents, later served as the model for the fictional Macondo in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

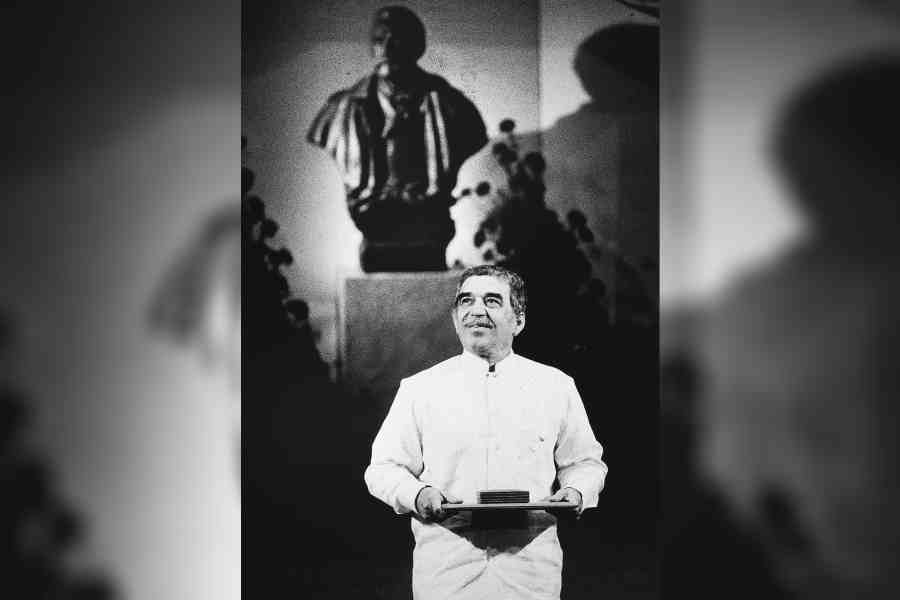

Marquez (C) arrives for the 28th New Latin American Cinema Festival at the Karl Marx theatre on December 5, 2006, in Havana, Cuba, even as his friend, President Fidel Castro, temporarily transferred his powers as president to his younger brother Raul Castro, the defense minister, due to his failing health. Picture: Getty Images

Marquez in 2009. Picture: Festival Internacional de Cine en Guadalajara

Soon after his return to Latin America in 1957, Márquez married Mercedes Barcha Pardo, whom he had proposed to before leaving Colombia for Europe. They were married on March 21, 1958. They had two sons, Rodrigo, born in 1959, and Gonzalo, born in 1962.

Throughout the early 1960s, as the Harry Ransom Centre points out, Márquez continued to work in journalism, including for the Cuban news agency Prensa Latina in Cuba and New York, and then writing for publishers and advertising agencies in Mexico City. He published what would become his most successful and well-known work Cien Anos De Soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude) in 1967.

This marked a life-changing time for him as he became primarily known for his fiction rather than for his journalism, and he achieved worldwide recognition as a gifted storyteller. His success as a writer also established him as a member of what became known as the “Latin American Literary Boom”, along with Julio Cortázar, Carlos Fuentes and Mario Vargas Llosa. The success of One Hundred Years of Solitude would also contribute to his 1982 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Following the 1960s, García Márquez continued to produce highly regarded works of fiction, including El otoño del patriarca (The Autumn of the Patriarch, 1975), Crónica de una muerte anunciada (Chronicle of a Death Foretold, 1981), El amor en los tiempos del cólera (Love in the Time of Cholera, 1985), El general en su laberinto (The General in His Labyrinth, 1989), and Del amor y otros demonios (Of Love and Other Demons, 1994). He also continued to produce non-fiction works, including La aventura de Miguel Littín, clandestino en Chile (Clandestine in Chile: The Adventures of Miguel Littín, 1986) and Noticia de un secuestro (News of a Kidnapping, 1996).

In addition to his writing, García Márquez involved himself with politics in Latin America and was a strong supporter of Fidel Castro of Cuba. He was consequently denied a visa to travel to the US, but the travel ban was lifted by US president Bill Clinton when he came into office.

The Harry Ransom Center confirms: “In 1999, García Márquez was diagnosed with lymphoma and underwent treatment in Los Angeles after which the illness went into remission. The event prompted him to work on his memoirs, and the first volume of a projected three, Vivir para contarla (Living to Tell the Tale), was published in 2002. His last work of fiction, Memoria de mis putas tristes (Memories of My Melancholy Whores), was published in 2004. The remaining volumes of his memoir, as well as a novel, En agosto nos vemos, were never completed.”

The Colombian-born writer’s allegorical novels represent and rewrite history and contest issues of separation, loss, power, patriarchy and identity through his unique brand of using fantasy, the fabulous and magical realism.

Surreal characters, a profuseness of synaesthetic imagery — touch, smell, audial, visual — impossible situations a la Cervantes and Zulfikar Ghose, opulent and meandering sentences, outrageous humour, and an effusive and melodramatic prose style are his characteristics as an inimitable writer. His irreverence and extraordinary ability to ferret out the senseless methods power uses to project ‘truths’ make him an exceptionally inventive writer who dares cock a snook at sensitive religious and political subjects. making him a controversial figure.

Champions of García Márquez’s novels relish his portrayal of marginal communities. He lights the spark that reveals the multitudinous forces of hybridity that is the essence of Latino society in Colombia. The layering of language, registers of spirituality and profanity, gender and race all appear simultaneously in his fiction.

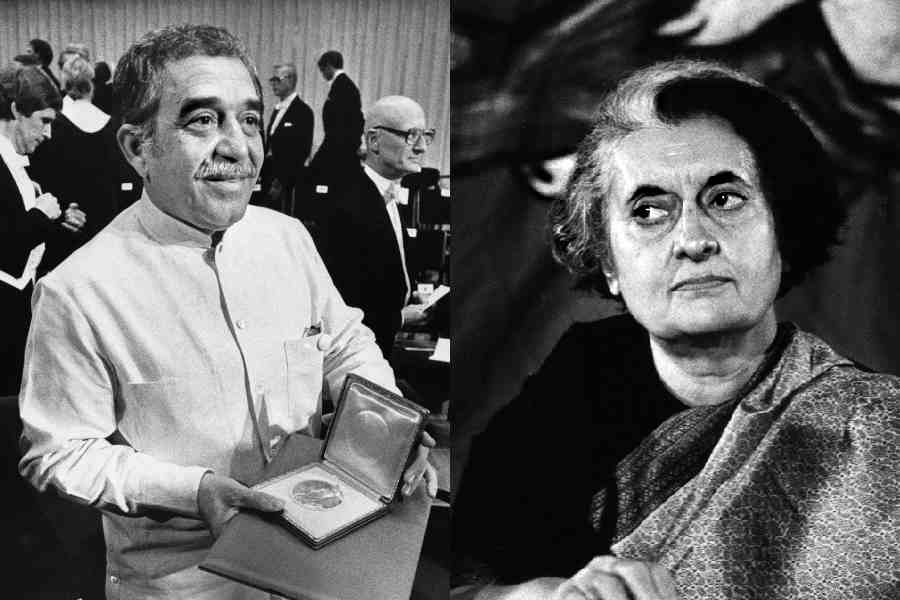

(Left) Marquez with his Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982 (Right) Indira Gandhi. Picture: Getty Images

Also sharply aware of exploitation and human rights abuse, as well as the presence of the supernatural in the real world, his newest to be posthumously published novel, based on the short story See you in August, is peppered with elements of magic realism, where the reader is left wondering about Ana, the lover of the protagonist.

In his epic story One Hundred Years of Solitude, he shows a unique ability to sniff out the evils within capitalist economies. The Banana Company is the perfect Colombian representation of the invading imperialism that the newly-created town Macondo falls prey to. Despite the glitz and glamour of outward progress, the Banana Company, located in the small town of Macondo and owned by Gringos or Americans, takes a heavy toll on this pre-industrial village.

Marquez, through his unravelling of the story of 17 Buendias, shatters all the myths of progress because he shows how most of the ‘progress’ is achieved at the cost of human rights, when wily colonialists or local collaborators with the colonial masters bring death — both spiritually and literally: “Macondo had been a prosperous place and well on its way until it was disordered and corrupted and suppressed by the Banana Company.”

Furthermore, Marquez’s fiction represents the hybrid reality that was his lived experience. He lived in a context where different races and cultures coexisted for centuries. Aracataca, where Marquez was born, lies on the Caribbean coast of Colombia. The novelist who put Colombia on the world map of literature, celebrates the jamboree of linguistic and cultural melange — pre-Colombian, Spanish and African.

“In the Caribbean, to which I belong, the overflowing imagination of the black African slaves was mixed with that of the pre-Colombian natives and then with the fantasies of Andalusians and the Galicians’ worship of the supernatural.... I believe the Caribbean taught me to see reality in a different way, to accept supernatural elements as something that forms part of our daily life,” Marquez has said consistently, in interviews.

He also feels indebted to the stories told by his grandparents, with whom he lived until the age of eight: Unbelievable supernatural stories his grandmother narrated with the utmost naturalness together with real war adventures related by his grandfather, the Colonel Nicolás Ricardo Márquez Iguarán.

It is this personal background that favours the intersection of different world views. As Brenda Cooper argues, hybridity “has been shown to be a fundamental aspect of magical realist writing. A syncretism between paradoxical dimensions of life and death, historical reality and magic, science and religion, characterises the plots, themes and narrative structures of magical realist novels.... The plots of these fictions deal with issues of borders, change, mixing and syncretising. And they do so... in order to expose what they see as a more deep and true reality than conventional realist techniques would bring to view”.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College