The bond between Bengalis and sweets seems almost eternal. In Bengali households, mishti often marks both beginnings and culminations. The world revolves around them. Sweets are also a quintessential part of Kolkata’s culture. So ingrained is mishti in the city’s ethos that some mishtir dokans now also sell diabetes-friendly variants of their classic offerings.

There is more to the mishti than meets the eye, or for that matter, one’s tastebuds. It also reflects the socioeconomic structure of West Bengal and the state’s geographical peculiarities. The history of sweets is even rooted in science. Every individual sweet often has its own story of advent and appropriation. Take the rosogolla, for instance. Even though Bengal has been awarded a GI tag for this juicy delight, the rosogolla is spongier in Kolkata than in other parts of the state. The langcha one buys in Kolkata resembles a pashbalish (bolster) and is usually brown in colour, but in Shaktigarh, this sweet resembles the khol, a musical instrument, and looks blacker. Added to this, pedas in Bengal’s temples all taste different.

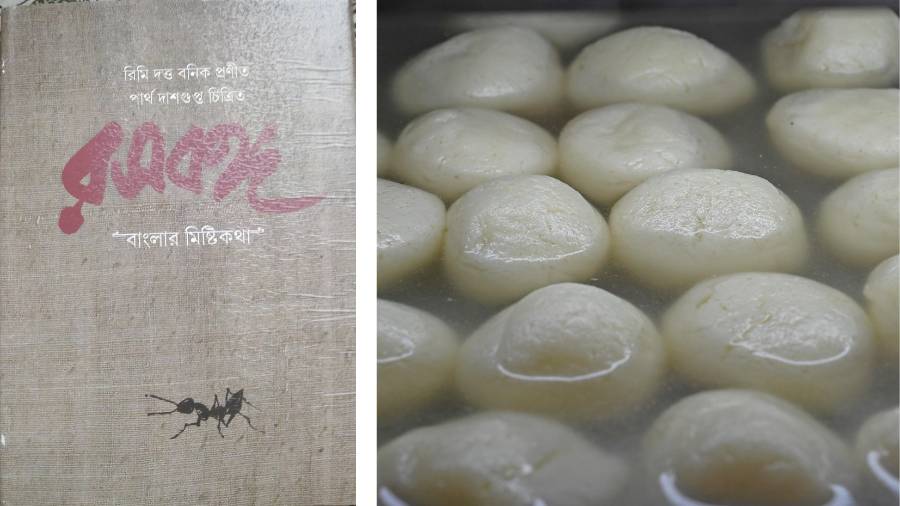

Rimi Dutta Banik's book 'Rasabanga' traces the journey of many famous Bengali sweets like the 'roshogolla' Barnini Maitra Chakraborty, Amit Datta

In her book Rasabanga, Rimi Dutta Banik explores different facets of Bengal’s sweets — the socioeconomic and political conditions in which they were made, as also geographical differences that have created variations in taste and appearance. Banik makes the world of mishti feel like a universe. The stories she tells us are all fascinating and layered.

A still from the movie 'Rosogolla', which traces the journey of Nabin Chandra Das Courtesy Windows Production

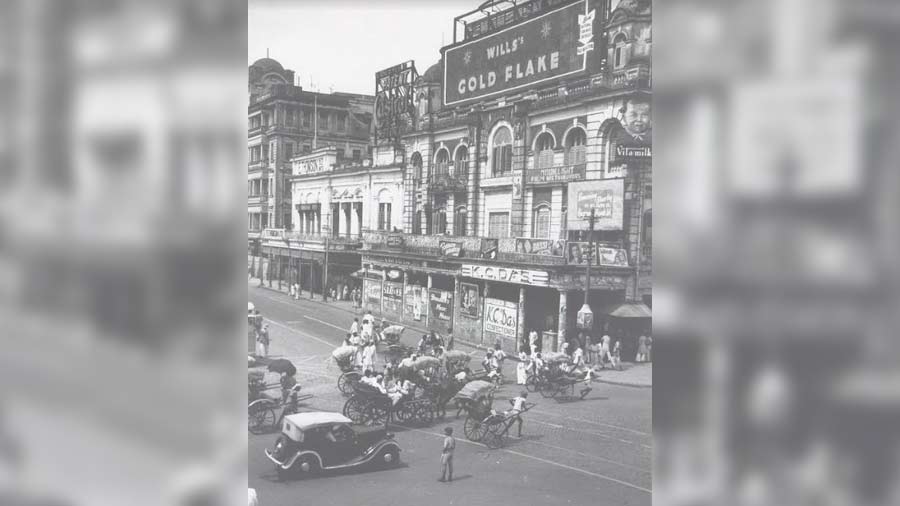

The story of Nabin Chandra Das is perhaps a good place to start. The man who gave Bengal the famous roshogolla is sometimes considered a Columbus, but his first creation was a sweet called ‘Baikuntha Bhog’. Known for his experiments, Das has also been credited with the creations of sandesh like the raatabi and abar khabo. It is believed that the queen of Cossimbazar once asked Das to make her a new kind of sweet. Das mixed together chhana, green coconut pulp, malai and elaichi for his invention. Upon eating it, the queen, it is said, wanted more. Her demand — “abar khabo!” — gave the sandesh its name. After Das’s death, his son Krishna Chandra Das furthered his legacy. He simmered small balls of chhana in milk and made rasmalai. This recipe is still in use at the sweet shop KC Das at Esplanade.

The K.C Das shop at Esplanade in the 1940s Wikimedia Commons

The creation of kanchagolla, another famous sweet, also has a story attached to it. Around the year 1760, in a place called Natore (now in Bangladesh), there existed a sweet shop that was named after its owner Madhusudhan Pal. Seeing that a lot of chhana would soon go to waste, Pal once mixed sugar syrup to it and boiled it for some time. When he saw that the mixture tasted scrumptious, a new mishti was born. Since the chhana hadn’t been treated before simmering, the sweet came to be called ‘kanchagolla’ (kacha translates to ‘raw’). The sweet is today made and sold by most sweet shops in the state, either with sugar or jaggery.

Gurer 'kanchagolla' at Nakur sweets Amit Datta

Bhairav Chandra Nag, a renowned sweet-maker in Burdwan, was the first to make sitabhog and mihidana. In 1904, the then Raja of Bardhaman, Maharaja Vijaychandra Mahtab, ordered Nag to make two new sweets to honour Lord Curzon who was visiting the area. Having mixed rice and flour, Nag fried his concoction in ghee and then dipped it into a sugar syrup, creating sitabhog. Mihidana, which also Nag fried and dipped in syrup, was made with pulses. History has it that Lord Curzon was amazed. Nag was even awarded a certificate for creating these delicacies. mihidana and sitabhog are now available throughout Bengal.

'Chhanabora' in Murshidabad and (right) 'sitabhog' in Burdwan Wikimedia Commons

In Murshidabad, the chhanabora is very popular. While Potol Ustad is remembered for having finessed this sweet, the chhanabora that Gopeshwar Saha would make in Nimai Mondol’s Murshidabad shop would be sent to the palaces of Murshidabad’s nawabs. Bhim Chandra Nag, too, has made many different sweets. In 1928, when Motilal Nehru had come to Calcutta to attend a national Congress meeting, Nag had created a special sweet called the Nehru Sandesh to commemorate the occasion. Nag also named the sandesh ‘Ashubhog’ after his regular customer, writer Ashutosh Mukhopadhyay.

(Rasabanga has been published by Khosrakhata and is available at their College Street stall.)