I met Ustad Zakir Hussain just four months ago. Sitting in the front row with me as my son, Anubrata Chatterjee, played on stage, he turned to me and asked, “Anindobhai, has Bubui (as he fondly called my son) not brought his good tabla?”

When I agreed with his assessment of the instrument’s quality, he told one of his students to give Anubrata his own tabla, which he would play later during

the event.

This incident perfectly captured the essence of the man and artist that Zakir Hussain was. As an artist, he was keenly attuned to rhythm, its consonance and dissonance. As a veteran musician, he would go out of his way to help other musicians, especially youngsters. As a human being, he was magnanimous and thoughtful.

It’s hard to believe that my beloved Zakirbhai is no more. His passing leaves a void in the world of percussion and, indeed, Indian music. After maestros like Pandit Kishan Maharaj and Pandit Samta Prasad, Zakirbhai had ushered in a new era of Indian percussion.

He not only learnt at the feet of his father, Ustad Alla Rakha, but was also influenced by the Western greats while studying at the University of Washington, Seattle.

A child prodigy, he collaborated with Indian classical music greats like Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan and Shivkumar Sharma and global musicians like George Harrison and John McLaughlin.

While his style was forever rooted in the Hindustani classical tradition, Zakirbhai possessed an insatiable curiosity for music and rhythm that propelled him to explore other genres, leading to ground-breaking collaborations across the world.

He did a lot to popularise the tabla globally and raise the stature of those who play this instrument.

Although his father, a proponent of the Punjab gharana, was his guru, it would be impossible to deny the influence that Ustad Ahmed Jan Thirakwa had on Zakirbhai. From him, Zakirbhai imbibed the passion to meld the aesthetic values of various gharanas.

Ustad Thirakwa left a deep imprint on Zakirbhai’s oeuvre. At his hands, the beats of Punjab, Delhi, Farrukhabad and Lucknow melded to create a rhythmic style unique to him.

He was a master at improvisation. While others may struggle to show their spontaneity even in a 16-beat cycle, Zakirbhai needed a mere two or four beats to innovate. It is thus not surprising that perhaps the most stunning aspect of his playing was the upaj, when he played extempore, creating interesting intricacies that captured the imagination of aficionados and lay listeners alike.

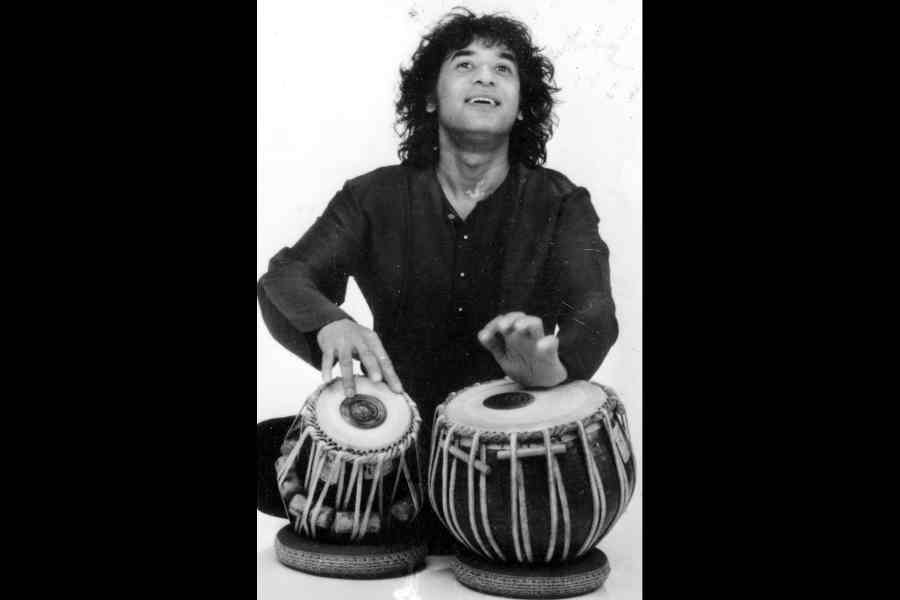

Ustad Zakir Hussain with Pandit Anindo Chaterjee in August Sourced by The Telegraph

His sangat with other artistes was a treat to behold — he challenged, inspired and complemented his fellow musicians on stage without letting his ego get in the way.

Zakirbhai also acknowledged his regard for Bengal’s Pandit Jnan Prakash Ghosh. He never failed to underline the state’s contribution to the world of Indian percussion.

Zakirbhai was one of those rare musicians who are extremely serious about their art but never take themselves seriously. Despite his worldwide success, he had not an iota of ego. He always had a joke or a kind word for his fellow artistes.

I remember an incident. I had gone to meet his father, Ustad Alla Rakha. Zakirbhai — aware of my fondness for mutton — ran away with my bowl of mutton curry and hid it, much to the amusement of everyone present.

Another time, when Ihad walked in while he was practising for an event, he joked: “Dekho, Anindobhai mujhe ghabrane ke liye aa gaye.”

This was more than a moment of levity; it was his way of appreciating other artistes.

In 1978, when he was a teacher at the Ali Akbar College of Music in California, I had come to see him while he was conducting a class. He immediately announced that it would be me and not him who would conduct that day’s class.

He had only respect and encouragement for other artistes. He never had a bad word for anybody, nor do I know of anyone who had something bad to say about him. This is what made Zakirbhai the great musician he was — his refusal to let success define his behaviour.

He had a way of drawing people in and making them feel included. Once, having found out that I was in Mumbai on his father’s death anniversary, he invited me to accompany him and a few other musicians to the Mahim Kabrastan, where we cleaned his father’s grave and offered a chadar.

At an informal gathering afterwards to pay tribute to Ustad Alla Rakha, in the presence of artistes like Sivamani, Suresh Wadkar and Shankar Mahadevan, someone fetched two tablas for us to play. Ever attentive towards his fellow musicians, Zakirbhai found and handed me a mask.

As I relive these memories, I can still feel the warmth of the hugs he gave me whenever we met.

Pandit Anindo Chatterjee is one of the foremost tabla players of India. He belongs to the Farrukhabad gharana.