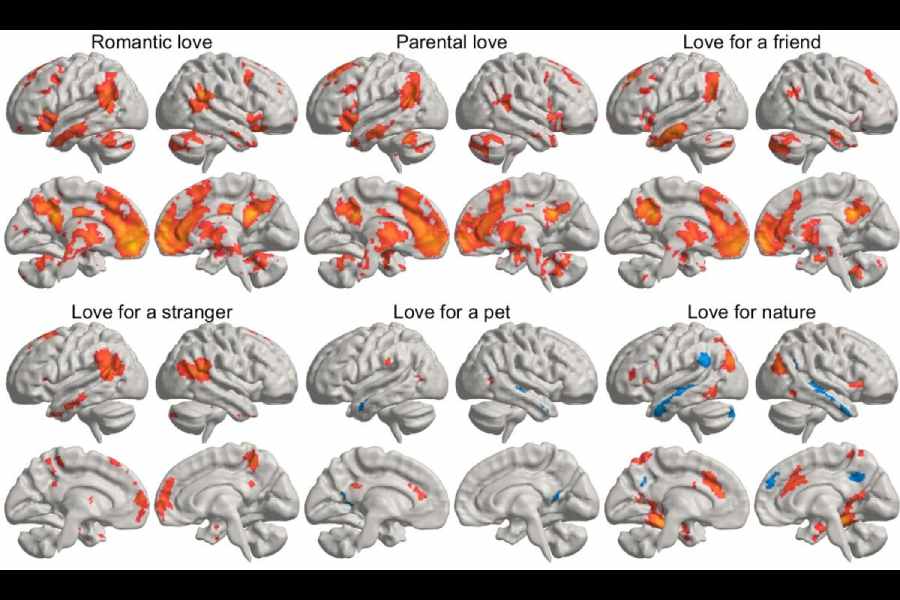

Scientists have generated the most comprehensive magnetic resonance imaging maps of brain activity triggered by different types of love: parental, romantic, love for friends, compassionate love for strangers, and love for pets and nature.

Their study has found that love in close interpersonal relationships such as for children, romantic partners, or friends is associated with significantly stronger activation in the brain’s reward system than love for strangers, pets or nature. All types of interpersonal love also activate the brain areas associated with social cognition — the set of neural operations required for social interactions. And in pet owners, love for pets activates these same social brain regions significantly more than in participants without pets.

The researchers say the big surprise in the study was the similarity in brain areas associated with love between people. “Intuitively, we might think that love for one’s children or romantic partners and compassionate love for strangers are very different phenomena,” Parttyli Rinne, a scientist at the brain and mind lab at Aalto University, Finland, and the study’s first author, told The Telegraph.

“However, the neural activation patterns are quite similar in terms of the brain areas activated. But there are significant differences in the strength of the activation. Closer affiliations activate the reward system more strongly. Compassionate love for strangers is weaker in terms of reward,” Rinne said.

Rinne and his colleagues used short pre-recorded stories designed to induce feelings of love in a set of 55 volunteers and generated MRI images of their brains during the process. The study was published in the research journal Cerebral Cortex on Monday. The images generated show that neural activity associated with close interpersonal affiliations such as parental love or romantic love is much stronger than activity observed in love for pets, strangers, or nature.

Earlier studies have suggested that pair bonding and parental attachment spark the same brain areas in both prairie-voles and humans. The activity occurs in evolutionary old brain regions, deep and close to the centre of the brain, in the brain stem and in regions just above it with projections to more superficial structures close to the midline of the forehead, Rinne said. “We are dealing with what is called the reward system of the brain,” he said.

Love for nature also activates areas within the reward system but does not activate the brain areas for social cognition. Instead, the researchers found activation in visual areas associated with looking at landscapes. “The love that pet owners feel for their pets is neurally more resemblant of interpersonal love than the love that non-pet owners feel for pets,” Rinne said.

The researchers have said they are hoping such studies will guide philosophical discussions about the nature of love, consciousness, and human connections and enhance mental health interventions in conditions such as attachment disorders or relationship issues.