On the Namkhana-bound local train from Sealdah, two women argued over the best way to get to the Makar Sankranti Bhanga Mela. One of them was saying, “You can hail a toto from Jaynagar station. I shall get down there and visit the mela with my mother.” The other woman, cradling a toddler, insisted, “If you get down at Mathurapur Road station and walk ahead, you will see the mela. Why waste money on a toto?”

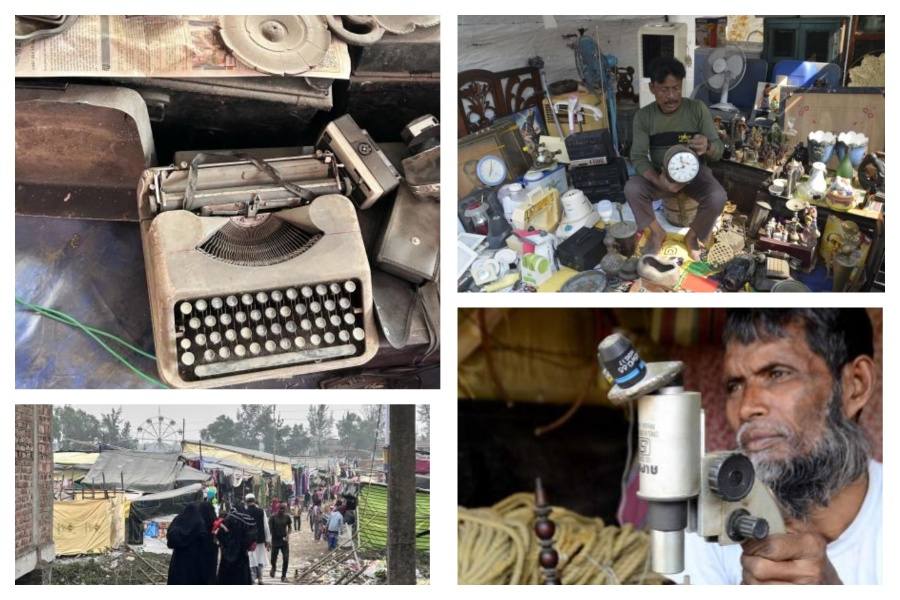

Bhanga mela as the name suggests sells broken things — typewriters, harmoniums, old passports, telephones, law books, rusty motor pumps, door hinges, fishing nets, old cassettes, shoes. But that doesn’t seem to deter people from neighbouring Kakdwip, Namkhana, Gocharan, Raidighi, Gangasagar and even Calcutta from flocking to it. Stalls come up in early January, and the fair itself starts on the day of Makar Sankranti and continues till the end of the month.

By the time the Namkhana local train pulls out of Mathurapur Road station, the platform is empty. A sea of people can be seen moving along the narrow rail tracks as far as the eye can see. They know that the next train is not due until another hour, and they also know that the rail tracks are the shortest route to the bhanga mela.

There is no one fairground. Instead, there are patches of land on either side of what looks like a rather withered main road. There are waterbodies covered with water hyacinth separating the road from these patches. Only makeshift wooden bridges can take you over them.

Babulal is running through a trunk full of junk at one of the stalls. Fountain pens, clocks, candleholders, hookahs, ghungroos and vinyl records are stacked here and there. He has come from Marquis Street in Calcutta.

Even as he fishes out a figurine or two, the shopkeeper loudly quotes his price — ₹200-300 a piece. Says Babulal, “Most of these have landed here from Calcutta and once again, I will take them back to the city and sell them to antique collectors.”

When families move houses, whatever they cannot take along ends up here. Under a red telephone set lies a laminated photograph of a sepia couple. There are two passports, both expired, one in 1999 and another in 1971. Customers rummage through a pile here, a heap there, in the hope of spotting rare things, useful things.

A man with a biggish bag stops before one of the stalls and points enthusiastically to a wooden clock whose hands seem to be stuck at 9pm. One look at his eager face and the shopkeeper quotes a stiff ₹300. In another part of the fair there is old furniture on sale. Carpenters are varnishing and painting sturdy-looking tables, beds, divans, chairs and whatnot.

Gokul Naskar from Jamtala, which is in the Sunderbans, inspects a table before he asks for its price. He tells The Telegraph, “Every year I come to this fair at least three to four times. Last year, I got a refrigerator from here for my sweet shop. This year, I am looking for a study table for my son.”

Another man sits inside a toto looking rather chuffed about the deal he has just struck. His helper is busy chaining a newish-looking sofa to the roof of the toto.

Then, there are rows of secondhand Sabooj Sathi cycles on sale. Sabooj Sathi is a West Bengal government scheme launched in 2015. Each year, bicycles are distributed free of cost to high school students of government-run institutions who are from disadvantaged backgrounds. Some of the cycles are missing a chain here or a handle there. The sellers quote ₹2,000 for cycles with the Sabooj Sathi logo and ₹2,500 for the branded ones.

There is a section for cars as well. An Alto without any documents, a Hyundai and a Maruti Van from 2017 stand cheek-by-jowl. Says Rajesh Mandal who is overseeing car sales, “We have sold four cars so far.”

YouTubers crawl through the fairground, camera and tripod in hand, capturing the spectacle for page likes and shares. A man haggles for a pair of wooden clothes hangers. Strewn about the place is a weighing scale missing a dial, steering wheels, workshop tools. As the clock strikes noon, many of the sellers pull out their tiffin carriers full of muri and start to mix it with ghugni sold at the mela food stall.

Mohirul, who has come from Diamond Harbour, has a curious collection of DVDs — Sholay, Anusandhan, Hirak Rajar Deshe, Alibaba, Charlie Chaplin films. He claims to have sold his entire collection of vinyls and now he stares fondly at his rows of cassettes. There is one with a yellow cover and the following words written in Bengali in a neat hand: “Ei gaan sob harabar. Ei gaan sob paoar.” Meaning, these songs are about losing everything. These songs are about getting everything.

Almost a ragtag anthem befitting a broken fair.