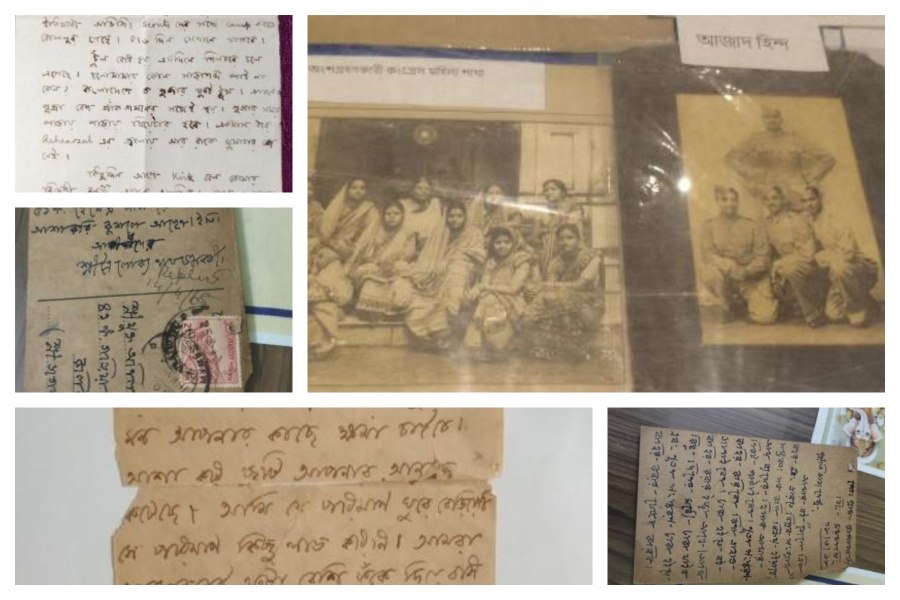

This year, when all of India was observing the 78th year of Independence, a gallery in south Calcutta — Maya Art Space — opened its doors to the collectors’ group, Kolkata Katokatha. It was an exhibition of items, all related in some way or the other with the Freedom Movement. There were photos, pens, Swadeshi matchboxes, sindoor kouto, autographs, currency notes, newspaper cuttings... And, letters written by freedom fighters.

Handwritten despatches by men and women, well-known and unknown. Letters from a husband to a wife, from a father to a son, from a son to his mother. Exchanges between friends. Postcards. Inland letters.

The papers worn, brittle. The envelopes yellow with age. The names on them even older, from another time — Sachindranath, Phanibhushan, Durgadas, Reba, some just illegible scrawls, some luminous, famous.

The dates range from 1890 to 1998. The letters crisscross India — from Allahabad to Calcutta, from Calcutta to Dhaka, from Andaman to Delhi. The subjects are varied.

There is a letter by Manmathnath Gupta, who was among those arrested in connection with the Kakori train robbery of 1925. A train from Shahjahanpur to Lucknow was robbed en route at Kakori. It was carrying taxpayers’ money to the British government treasury. Among the revolutionaries were four of Gupta’s friends — Ram Prasad Bismil, Rajendra Lahiri, Ashfaqullah Khan and Roshan Singh. They were sentenced to death. Gupta alone survived to tell the tale.

Half a century later, Gupta writes to Professor Ali Ayyub about how the memory still haunts him. Gupta, who had been sentenced to 14 years of imprisonment, also writes about Mani Banerjee who breathed his last in his arms in prison.

Trailokyanath Chakra-borty had been sent to the Andaman Cellular Jail in the Barisal Conspiracy Case of 1913. In 1968, he wrote from Mymensingh to Anil Chandra Ghosh in Calcutta about his memoirs based on 30 years spent in prison.

Some of the letters are written on printed letterheads with names such as The Forward Publishing Ltd, All Bengal Political Sufferers’ Association and Loke Sevak Sangha.

The letters displayed are from the personal collections of Jayanta Kumar Ghosh, Sirsendu Mukherjee, Ujjwal Sardar and Arup Ray.

Mukherjee, who teaches statistics in a south Calcutta college, makes his harvest from auctioneers and antique collectors. In addition, whenever a house is being pulled down, he keeps a lookout or someone alerts him. He says, “There is a chain in place.” Sardar recalls a letter he found inside a secondhand book. It stoked his interest in collecting letters.

Ray is ailing and cannot be interviewed, but the other collectors claim he is the only one of them to have collected the letters directly from revolutionaries and their families. “Good things find good homes,” says Ghosh.

The letters from the exhibition speak of not just a different time but a different culture, a different society. The salutations and sign-offs are elaborate, respectful and radiate a certain humility.

There are all kinds of handwriting, myriad emotions, humour and above all, a sense of nation and nationhood — impassioned, not angry, not taken for granted. Sardar says, “It is not mindless scribbling. A lot of thought went into it, the way it was arranged

and structured.”

There is an exchange from 1945. Ajoy Kumar Ghosh, who was arrested in the Lahore Conspiracy Case in 1929, is writing to “Minu da”. In that case, Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev Thapar and Shivaram Rajguru were convicted for killing British police officer John Saunders and hanged. Ghosh was released due to lack of evidence. Among other things, Ghosh, who appears to be in Allahabad, talks about Jawaharlal Nehru, Purushottam Das Tandon and Govind Ballabh Pant touring the city and making impassioned speeches.

It feels a bit like time travel. There’s one from 1959 referring to the riots of 1950 in East Pakistan. Yet another from 1903 written by C.R. Das to his wife Basanti Devi. The missive is mostly faded but for the second page wherein one can decipher two words — Sarojda and jail. Another letter from 1949 by Hemchandra Kanungo to a publisher urging him to return his manuscript since they did not seem interested in publishing his book. In The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism, Carl Levy and Matthew S. Adams write how Kanungo went to France “specifically to learn how to make bombs from anarchists”.

Another one is from 1947, from a father to his children, on the occasion of Independence Day. Short letter. Telegraphic writing. It reads: “Independence Day. Make your country proud. That is my blessing. Tomader Baba.”

Even the nature of blessings have changed. No?