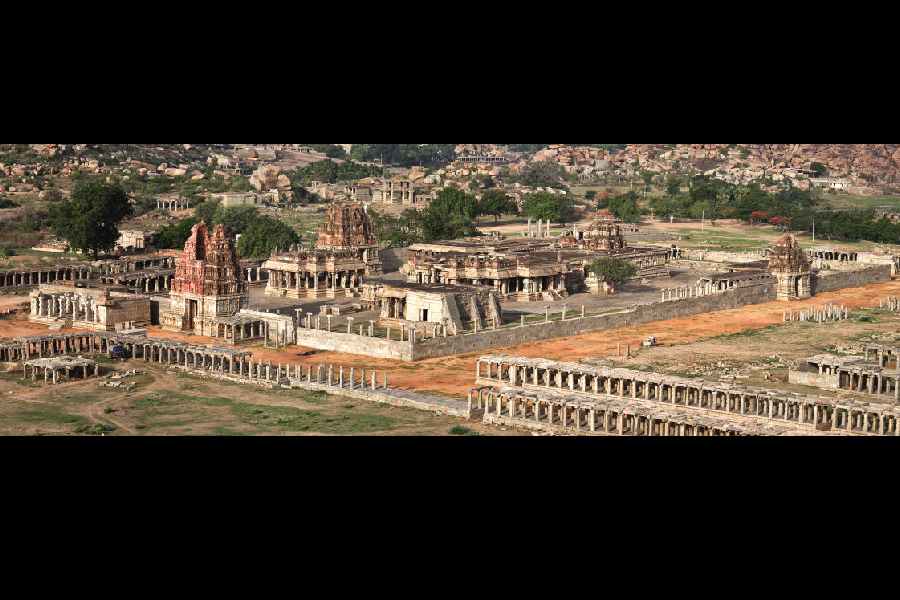

In the introductory pages of Tungabhadrar Teere (On the Banks of Tungabhadra), Sharadindu Bandyopadhyay’s well-known historical romance, the Bengali litterateur wrote about the short-lived glory of the ancient fortified capital city of Vijayanagara. It was built with the stone icon of Virupaksha, Shiva by another name, at its centre. Only 600 years ago, Bandyopadhyay wrote, the kingdom held sway over the Deccan, if only for 200 years. But within this short period of time, memories of the splendour of Vijayanagara had sunk into oblivion. People had forgotten the grand bequest hidden under the vast abandoned ruins of Vijayanagara on the south bank of the Tungabhadra river. Only Tungabhadra has not, the writer concluded.

George Michell, 80, a world authority on South Asian architecture, along with the late John M. Fritz, an American archaeologist, had unveiled the splendours of Vijayanagara in Karnataka after working continuously for 20 years from January 1980, in tandem with John Gollings, an Australian architectural photographer.

Lotus Mahal in Hampi. Photograph by John Gollings from the George Michell Collection

Michell was in Calcutta after 20 years in December 2024. During an hour-long illustrated lecture, he transported the audience in the packed hall of the Birla Academy of Art & Culture to the inhospitable site of the Victory City or Vijayanagara strewn with giant — Michell’s evocative adjective was “wild” — granite boulders that served as the raw material for creating this magnificent city. Between the 14th and 16th centuries, Vijayanagara became India’s wealthiest and most powerful kingdom. “The architecture belongs to the landscape”, remarked Michell.

The elephant stables in Hampi. Photograph by John Gollings from the George Michell Collection

There could not have been a better cicerone than Michell as he brought the audience up close with the “geography” and “history” of the Hindu empire of Vijayanagara. Its distinctive hybrid architecture amalgamated elements of Tamil temples and the Sultanate palaces of Gulbarga and Bidar. Its multi-cultural populace included Muslim servitors who took charge of the horses of the cavalry and even danced for entertainment. Michell concluded his lecture by sounding a warning about the management of this Unesco World Heritage Site, popularly known as Hampi.

Stepped tank in Hampi. Photograph by John Gollings from the George Michell Collection

In the 13th and 14th centuries, the Delhi sultans invaded the Deccan right up to the tip of India and destroyed all the old Hindu kingdoms. But after they retreated because of the huge distance from their throne, a power vacuum was created. Gradually, local people such as Sangama and his kin asserted themselves and created a new type of kingdom, Vijayanagara.

The invaders from Delhi had left behind their own governors who formed their own independent Sultanate kingdoms. They were in conflict with the Vijayanagara rulers for 200 years over territory and resources. In January 1565, the combined forces of the Deccan sultans plundered and pillaged Vijayanagara for six months after a “catastrophic” battle. What distinguishes Hampi’s “restricted” history is that it spans only 200 years.

Stepped tank in Hampi discovered by ASI in mid 1980s.

Sangama and his brothers exploited the arid and rugged landscape with its “interlocking mythologies” in terms of security and irrigation possibilities. The city plan “responds” to the dominating river and the rocky ridges. This is Kishkindha, where Ram had mustered his simian troops. Monolithic Hanuman and Ganesha are carved on the boulders.

In the 15th century, Ram is present in the middle of the royal centre but not many temples are dedicated to him. Outside, it’s only the king and his story. The militia, elephants and horses imported from the Arabian peninsula or the southern coast of Iran were part of the royal processions. The horses were led by Arabs.

In the carvings of temples built later, the Arabs were replaced by the Portuguese who had taken over the maritime trade in the Indian Ocean.

Here the local goddess Pampa of the river — after whom Hampi, actually a village, is named — had married Virupaksha or Shiva, and thereby assumed the powers of the pan-Indian Parvati. During the Mahanavami festival or Dussehra, the king worshipped Durga and was invested with her power. The giant figure of Narasimha, the man-lion avatar of Vishnu, was sculpted from a single boulder in the 16th century.

The sacred centre had the Virupaksha and Vitthala and other temples. Most of the populace lived in the huge fortified “urban core” at one end of which is the royalcentre. This is the only mighty Hindu imperial city where the “whole architectural range of a royal city life” has survived.

A cluster of temples on Hemakuta hills above Hampi are linked with Pampa. They belong to the late 14th-century style when Vijayanagara was Shaivaite. The south Indian style evolved in the 15th century as represented by the Balakrishna temple. When Michell and his team documented the ruins of Vijayanagara in the 1980-90s, it lay abandoned in a field.

In the 15th century, Chola-style architecture in the Tamil tradition was introduced — the lower portions were stone and the upper portions were brick.

In the mature period of the 16th century, huge slender columns were hewn out of a single block of granite that looked down on the towering gopura of another temple. The Virupaksha temple was constructed in the most“up-to-date” architectural style. King Krishnadevaraya built a coronation pavilion in 1513 that had a ceremonial mandapa.

The shrine dedicated to Tiruvengalanatha or Vishnu and his consort Lakshmi was constructed in 1530 towards the end of the Vijayanagara period on a grand scale. The temple was enclosed within two concentric walls. You could enter it through two towered gates down collonaded streets that had shops. When archaeologists removed the crops growing on it, underneath they found stone-lined streets which were a rarity in the 16th century both in India and Europe. The space was used for festivities.

After its destruction, the temple closed. Michell said when the ruler was absent, the temple took on the management of money and economics and sustainability of the city. The temple has an inscription to that effect and not about spiritual life.

Of Tamil origin, the multi-storeyed gopuras and mandapas became the hallmarks of the mature Vijayanagara style. The temple on the grandest scale was built in the 16th century and dedicated to Vitthala. This type of architecture enjoyed the patronage of Krishnadevaraya’s queens.

Carved relief panels on the Mahanavami platforms show a seated royal figure with Muslim men paying obeisance to him. In another panel, central Asian Turkic people wearing distinctive costumes, beards and hats perform a dance. “In the 12th and 13th centuries they had come with the invaders and were part of the Sultanate culture of north India. When the Tughlaqs retreated, these Turks stayed on and were employed by Vijayanagara kings”. Michelle stressed that Muslims were part of the court and some kings kept a Quran to take the oath of Muslim officers. Those who built temples and palaces also built mosques.

As in the palaces of Gulbarga and Bidar, plaster-covered masonry was used to build temples. The finest example of the hybrid style is the Lotus Mahal. This and the elephant stables within the royal centres were built in “a distinctly Islamic manner” “inspired by the contemporary architecture of the neighbouring Bahamani kingdom.” At first, “they looked like a cluster of Muslim tombs to us,” Michell recalled.

Praising the creativity of the architects, he said worship is still alive at the Virupaksha temple in Hampi village, attracting thousands. “Once upon a time, the colonnades were filled with bustling shops. But the local commissioner decided it was illegal at a Unesco World Heritage Site and destroyed all the shops and homes in the 1980s, ignoring the fact that it was traditional. There was no interaction with local people. The site was not managed well,” he concluded on a sad note.

Michell was in Calcutta on an invitation from the Tarun Mitra Memorial Lecture Committee of the American Institute of Indian Studies. On the previous day, he had given a lecture titled “In the Footsteps of David McCutchion: Brick Temples of Bengal” at the Jadunath Bhavan Museum and Research Centre of the Centre for Studies in Social Studies.

Michell had never met McCutchion, who died in Calcutta in 1972, but was called upon to complete the book the latter had begun by extensively documenting and photographing the terracotta temples of Bengal.

Michell did complete the book titled Brick Temples of Bengal: From the Archives of David McCutchion.

At the end of his lecture on how he completed book, Michell appealed to the audience that a sponsor should be found to fund the digitisation of the 15,000 black-and-white photographs David McCutchion had taken, now with the Victoria & Albert Museum. So rightfully, a copy of these frames should be in Calcutta, where it all began.