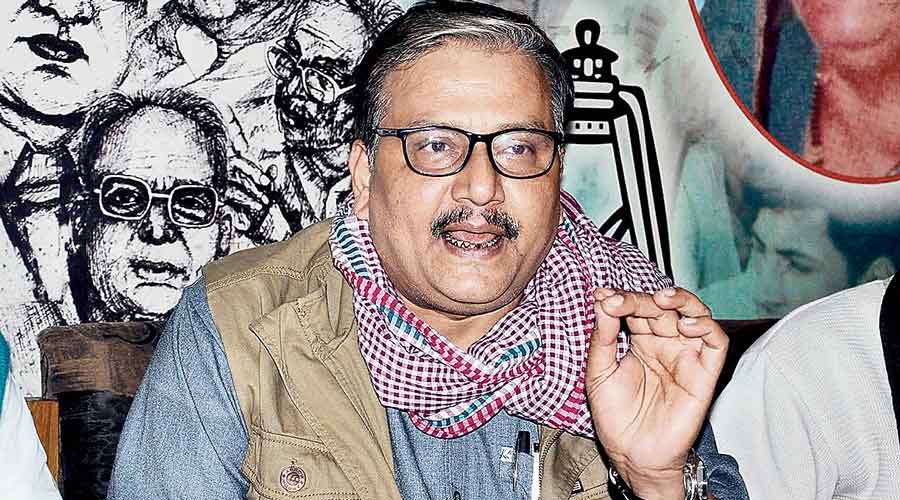

Rajya Sabha member Manoj Jha on Wednesday questioned the government on the rationale behind a University Grants Commission plan to introduce posts of “professor of practice”, to which people from industry can be directly appointed even if they lack a PhD.

Currently, anyone from outside academia who is directly appointed a professor or associate professor, without having to join at the lowest rung of assistant professor, needs to have a PhD in the subject.

Education minister Dharmendra Pradhan preferred not to answer Jha’s query, saying the supplementary question was unrelated to the main question on the teacher-student ratio in schools. Under the rules, supplementary questions should be related to the original question.

Jha, a Rashtriya Janata Dal member, had told the Chairman: “With your kind permission, Sir, I wish to ask the honourable minister through you, there has been a talk of associate professor of practice and professor of practice, and PhD, apparently, is no more in the inclusion criteria. Has it been done on the basis of some study? If yes, we would like to know the study. If no(t), why?”

A UGC official said the commission was planning to amend its rules to allow professionals from outside academia to be appointed professors or associate professors in general colleges, on contract or regular basis, according to the institutions’ requirements.

While details of the proposed norms for the appointment of professors (or associate professors) of practice are not yet known, Jha later told The Telegraph he was concerned about possible backdoor entry into academia by people with certain ideological leanings.

“My concern is that this seems an agenda prepared by Nagpur to facilitate the appointment of undeserving people at academic institutions,” Jha said.

Jha said: “If the government has done any study about the need for, and effectiveness of, such a system, it could have responded (to Jha’s question in the Rajya Sabha).”

Former IIT Delhi director Ramgopal Rao said the tech school had been appointing professors of practice for the past three years — up to a limit of 10 per cent of faculty positions in any department — and it had “proved beneficial”.

“People who have excelled in industry are appointed professors of practice. Their approach to problems is different — they have come out with new technology and prototypes too,” he said.

Rao said professors of practice could be appointed in the humanities and social sciences too: for example, eminent authors or publishers with a proven record of excellence could be recruited to literature departments.

Central University of Punjab vice-chancellor R.P. Tiwari welcomed the idea but said its success would depend on appointing the right people.

“The critical area is to identify the resource persons. People working in NGOs, research organisations, publishing houses, media organisations as well as professional artists, authors, musicians, singers and so on can be given an opportunity in the universities,” Tiwari said.

He suggested an induction course for the new appointees to familiarise them with pedagogy, evaluation, development of research proposals, curriculum development, commercialisation of technology, intellectual property rights, outreach and social equity.

Biju Dharmapalan, academic and former member of an expert committee on bio-science at M.G. University, Kottayam, said some foreign universities such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology did employ accomplished industry people as faculty.

“The concept is good if the profile of the person is exceptional. For example, there is nothing wrong with employing people of stature like Elon Musk or Bill Gates, especially in emerging fields like quantum computing/ artificial intelligence/ space research, etc. But in India, there is a possibility of the rule being misused,” he said.

“The rules should spell out the areas (of industry from where professors of practice for a particular subject can be recruited), the profile of the company (where the recruit may have been employed), and the basic expectations from the person. Otherwise, people working in mediocre companies that lack credibility might creep into the academic system and spoil it.”

Dharmapalan said industry people sometimes had a narrower view of a subject compared with an academic, and that this might affect the teaching-learning process.

“The purpose of university or college teaching is to provide broad knowledge about the subject. Usually, industry people focus only on application; they may not go deeper into the concepts and theories,” he said.

“If the rules allow anyone with industrial experience to become a professor, it will affect not only research but also teaching.”

Rajesh Jha, a Delhi University teacher, expressed fear that the reservation policy may be ignored in the appointment of professors of practice.

He cited the example of the Centre’s appointment of people from the corporate sector and NGOs directly as joint secretaries and deputy secretaries without following the reservation policy.