A post-graduate in sociology from Delhi University (DU) has received PhD admission offers from four UK-based universities but he fears he is unlikely to be selected under the revised National Overseas Scholarship (NOS) scheme.

A new provision excludes from the scholarship scheme students pursuing studies and research on Indian culture, history and social studies in foreign universities. The scheme is meant to help students belonging to the Scheduled Castes, denotified nomadic and semi-nomadic tribes, families of landless farm workers and the traditional artisan community.

The aspiring research scholar, who did not wish to be identified, said: “I wanted to pursue PhD on the caste issue. If I do not get the scholarship, I will not be able to fund my education. I will forgo the opportunity.”

Students, academics and lawmakers are coming forward to oppose the new guidelines that the social justice and empowerment ministry has defended by saying such “studies can be undertaken in top Indian institutes and central universities”.

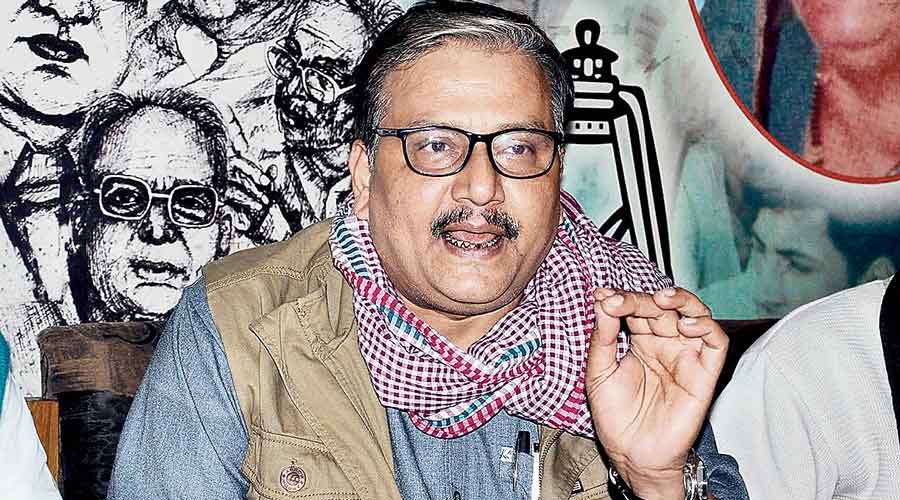

On Monday, RJD parliamentarian and DU academic Manoj Jha sought the intervention of Prime Minister Narendra Modi to drop the revised norms.

The “new, revised guidelines will only stifle academic freedom and excellence and prohibit our youth” from engaging constructively with their society, culture, heritage and history, Jha said in a letter to the Prime Minister.

Jha said that in the past five decades, the scheme had enabled thousands of students from disadvantaged social groups to study and carry out research in prestigious institutions abroad.

Curtailing the choice of subjects in such an “arbitrary manner is not only an assault on their academic freedom but also does not bode well for larger environment of knowledge creation in the country where there is arguably a great need to carry out critical social science research on historical as well as contemporary issues”, Jha said in the letter.

“I do not need to underline the importance of encouraging the youths to engage with their cultural and historical contexts. These potential young scholars will not only be producing valuable research work but also will strengthen the larger Indian academic environment,” Jha wrote.

N. Sukumar, a faculty member of political science in DU, disagreed with the ministry’s contention that Indian institutions were best suited for research in Indian history and social science.

“Barring exceptions, in many Indian universities, research on caste, social exclusion, discrimination and Dalit citizenship is not encouraged. And knowledge needs to be transcended across the globe. The government’s defence is not tenable,” Sukumar said.

He said the National Education Policy reinforced the need for inter-disciplinary research. Many topics related to caste, gender and poverty are inter-disciplinary in nature, which should be promoted, he added.

He said research on Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar was started in India by foreign scholars such as Gail Omvedt.

“This government does not want research on subjects that Ambedkar researched long ago and contributed immensely to the social consciousness in Indian society. The government does not want more Ambedkerites to do research. This is an injustice against Dalits by the social justice ministry,” he said.

Deepak Malghan, a faculty member at IIM Bangalore, said the modified guidelines would worsen the low presence of faculty members from marginalised sections in academic institutions.

“Many faculty members at elite Indian institutions have been trained abroad. Almost all of these academics are drawn from a tiny sliver of upper caste groups. The acute diversity deficit at our institutions will worsen as a result of this misguided policy,” he said.

He said many marginalised students go abroad to escape the “no merit” insinuation that follows them on Indian campuses.