Among the millions who crossed the great divide in the north was six-year-old Balbir Singh Suri. Leaving their home in Jhelum district, now in Pakistan, the Suris survived on “roti and achar given by the army”, cowering in a truck that brought them to Patiala in India’s Punjab.

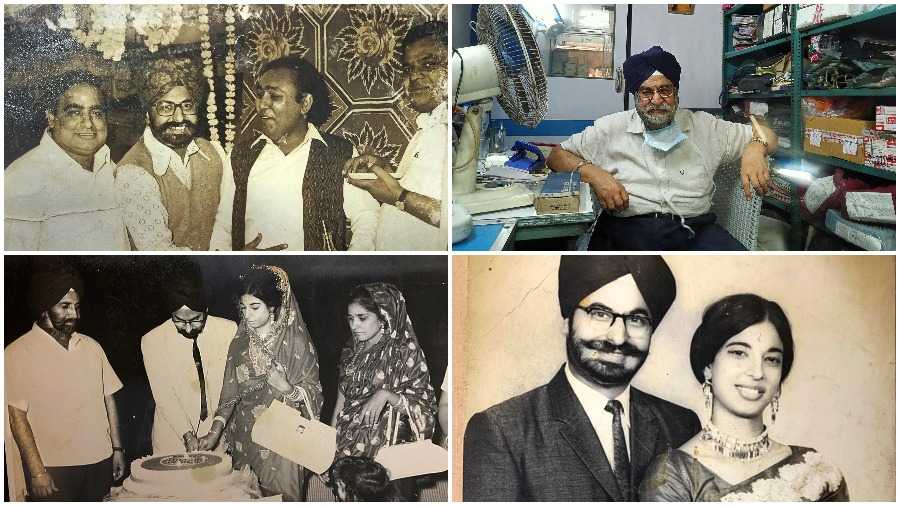

Sitting in his Princep Street office in central Calcutta today, the 81-year-old covers his ears with his palms, shuddering, “People dying, people killing... Kaat ke udhar se idhar phenk raha thha aur idhar se udhar. Have you seen that film Bhaag Milkha Bhaag? It was exactly like that.”

The vivisection of India in 1947 led to one of the largest mass migrations in human history. The 3,323-kilometre Radcliffe Line, announced just two days after the declaration of Independence, sliced up the populous states of Bengal and Punjab. Over a million were killed, 15 million displaced and countless others simply disappeared.

The Sikh community had been part of Calcutta from way before Partition. In the essay, The Other Sikhs: Punjabi-Sikhs of Kolkata, Himadri Banerjee writes, “As the railways facilitated travel between these two distant parts of the British-Indian Empire, Sikhs had reasons to come to the metropolis. Their link with the capital of the British-Indian Empire went back to the mid-nineteenth century when they had passed through the city, on the way to China to fight in the Second Opium War (1858-61).” But after Partition it became home to several refugees from West Punjab.

The Dhan Pothohar Bradri — biradri means brotherhood — consists of some 440 Punjabi families, mostly Sikhs. It was founded in 1948 by one Chattar Singh Rekhi as a self-support system for all those who had migrated from West Punjab. A booklet-cum-directory of the society enumerates one of its objectives as — “To create brotherhood among the families of Dhani, Pothohar and Sohann comprising the districts of Rawalpindi, Jhelum and Campbellpur (now in Pakistan) residing in Calcutta.”

Taranbir Singh Mokha, current president of the Bradri, says, “My father told me that when these people came, somebody had expired. They didn’t even have four people to lift the body. That’s how the idea came up...”

According to the 2011 Census, the Sikh population of Calcutta was 13,849, which was 0.31 per cent of the total population of the city. In 1951, the community constituted 0.56 per cent of Calcuttans and in 1961, 0.51 per cent.

“Compared to other parts of India, the number of Sikhs who came over to Calcutta after Partition was less because West Bengal was grappling with the problem of Hindu refugees from East Pakistan,” explains Banerjee, former Guru Nanak Professor at Jadavpur University’s department of history. But numbers are hardly indicative of the community’s strength or presence in their adoptive home.

Banerjee writes that during the pre-Partition years, Calcutta’s Punjabi-Sikhs made their presence felt “from the domain of surface transport to the sphere of literary activity. Participation in the city’s nationalist politics as well as their tie with the Left ideology made them partners in the anti-colonial struggle”.

So when Mokha’s father arrived in Calcutta in the 1950s, it was not entirely a journey into the unfamiliar. In the many-layered Punjabi migrant and Calcutta narrative, the Partition migrants from West Punjab form just one chapter, one thread, if you will.

Mokha’s grandparents were from Rawalpindi. His grandmother was a high school teacher and grandfather had a small business. Soon after Partition, he expired. His grandmother got a teacher’s job in Ambala and that is how she brought up her children. Mokha says, “My father got a chance to come to Calcutta, he was 16 then, because a relation had already come here and started a business.”

No two families had the same journey. For Jhelum’s Suri family, the first stop out of Pakistan was Patiala. “The Maharaja of Patiala helped us a lot,” says Suri. They then moved to Delhi and thereafter to Dehradun where his maternal uncles had found a footing. When he couldn’t pass matriculation, Suri landed in Calcutta as a 15-year-old to join his cousin in the motor parts business. That was 1955.

Suri slept on the pavement for a whole week before securing a corner near the stairway of a building in the same lane, but the elderly gentleman’s mein turns pure joy as he talks about what kept him going — hockey. “At 6 every morning we would go to the Maidan. And you know what, no bus conductor or tramwallah would charge us for tickets! Even taxi drivers gave us free rides, saying ‘you are players’.”

Three years down the line, Suri was on his own — “jhola niye, maal niye”. Opportunity was yours to grab, he explains in fluent Bengali, you earned as much as you toiled. “We were in the market by 9am. And the grind continued till 10 or 11pm.” His own shop materialised in 1964.

In time, a match “made in heaven” was initiated by a gentleman across the street, his would-be-wife’s uncle. A graduate from Shimla, her family too had migrated from Pakistan.

Hari Om Batra, president of the Calcutta Punjab Club, is into the finished leather business and also owns a finance company. His grandfather and his five children were living in Sargodha (now in Pakistan) district when destruction came knocking on their door. Give us your girls and we will leave you — was the thing going around.

The family fled overnight with whatever jewellery they had, first by bullock cart and then by train. They stayed in a refugee camp in Delhi before moving on to Ambala, where they were allotted some land. But that was hardly sufficient for a big family such as theirs. Batra’s father, then in his early twenties, commuted to Jalandhar to sell balloons, clothes and the like, travelling ticketless and often pulled up by the railway checker.

Still searching for sustenance, one part of the family shifted to Agra, where they came in contact with some Muslim families. “They were Khurja Muslims who were engaged in the leather business,” narrates Batra. Providence or coincidence, they were planning to shift to Pakistan. A sort of barter was carried out — leather work in exchange for help with the Batra family’s own jaggery business back in Sargodha.

It was leather that occasioned Batra’s father’s frequent visits to Calcutta — a leather hub even then. Much later, in 1960-61, they rented a small office space — one room in Chandni Chowk; this meant they didn’t need to rent a place for the nights. Says Batra, “I recall coming with him when I was six or seven. We laid out mattresses at night and by morning it was back to business. About 10 years down the line, my father bought an apartment in Karnani Estate on Park Street along with a group of friends…”

And the West Punjab stories abound, of Partition induced migrations and movements to Calcutta. They are little known perhaps given their numbers, especially in comparison to the influx from East Bengal and perhaps because they are difficult to fathom given the leap of geography they entail. But they are there nevertheless, a true and an indelible part of the Calcutta mosaic.