Justifying his decisions, Radcliffe, in an interview with veteran Indian journalist Kuldeep Nayar, said, ‘I had no alternative; the time at my disposal was so short that I could not do a better job. Given the same period I would do the same thing. However, if I had two to three years, I might have improved on what I did,’ adding, ‘if aspirations of some people had not been fulfilled the fault must be found in political arrangements with which I am not concerned’.

He was probably referring to comments like the one made by the Pakistani newspaper Dawn, which called it ‘territorial murder… Pakistan has been cheated by an unjust award, a biased decision, an act of shameful partiality by one who had been trusted to be fair because he was neutral’. In the interview with Nayar, Radcliffe said, ‘I nearly gave you [India] Lahore. But then I realised that Pakistan would not have any large city. I had already earmarked Calcutta for India’.

He would later confess that he had relied on out-of-date maps and census reports, since it was ‘impossible to undertake field survey in June because of the heat’. He wasn’t very happy with the members of the Border Commission either, as the ‘natives’ were divided and had vested interests in the betterment of their own nations. Recounting his experience, he narrated to Nayar how a Muslim member of the Bengal commission asked him if he could include Darjeeling in Pakistan as his family went there each summer.

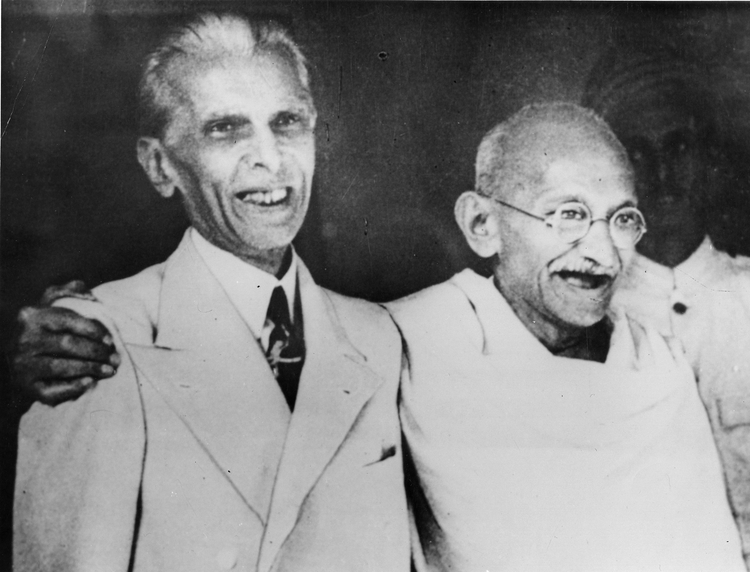

Through a series of mistakes committed by Radcliffe—as well as leaders from the subcontinent such as Jawaharlal Nehru, Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Sardar Patel—the cartographer’s work remains an open wound even today, and will forever define the two nations. It not only created Pakistan and, eventually, Bangladesh, separating the nations from India ideologically and geographically, but its waves also hit the shores of England, where numerous people, such as the poet W.H. Auden, responded to the absurdity of the division in his poem, ‘Partition’. Auden summarised the events that led to Partition, Radcliffe’s helplessness, the extent of the task he was bestowed with and its consequences, and wrote:

But in seven weeks it was done, the frontiers decided,

A continent for better or worse divided.

The next day he sailed for England, where he quickly forgot

The case, as a good lawyer must. Return he would not,

Afraid, as he told his Club, that he might get shot.

If nations are ‘imagined communities’, then what does one make of the borders that confine them? It is impossible to speak of India or Pakistan’s past in isolation without mentioning the ‘other’. The two nations, as they stand today, are separate entities with their own histories and ideologies. However, for people living life at the borderline, reality is not a matter of ideology or how history took a violent turn, it is simply a geographical notion of home. ‘Sometimes those assigned to run the pencil do so, without realising the impact that their line is going to have on humankind,’ wrote Bishwanath Ghosh in Gazing at Neighbours: Travels Along the Line That Partitioned India, adding, ‘Sir Cyril Radcliffe was one of them’.

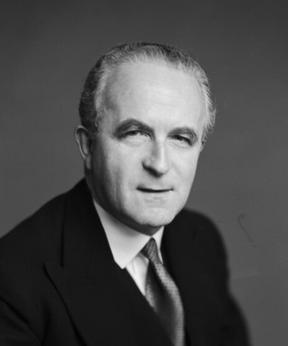

Radcliffe, a British barrister, set foot in India for the first time on July 8, 1947, when he was assigned the task of dividing the territory. He had five weeks to partition the Indian subcontinent and chair the two Boundary Commissions—one for Bengal and the other for Punjab. Each had four representatives—two from the Indian National Congress and two from the Muslim League. The division was not only supposed to focus on religious and socio-political divisions, but also on natural boundaries, water bodies and irrigation systems that would affect both countries.

On August 17, 1947, three days after Pakistan’s independence and two days after Nehru delivered his iconic ‘Tryst with Destiny’ speech, the final demarcations were announced. Radcliffe had drawn his lines on the map—the 553-km-long zigzag line that divided Punjab and the 4096-km line that halved the Bengal Presidency. But even before the lines that amputated the subcontinent were decided, blood had been spilt and violence had ensued along the borders. The demarcations would lead to decades of violence, war and conflict in regions such as Punjab, Bengal, and Kashmir—an area he was ‘not even aware of’ and would hear about only after he returned home. Appalled by the bloodshed, Radcliffe left for England, never to return to India. He burnt his papers and refused to collect his fee of Rs 40,000.

Sumanta Banerjee, writing in the Economic and Political Weekly, called Radcliffe’s division a ‘sloppy surgery’, while Bishwanath Ghosh said, ‘The surgical scars…will remain as long as India, Pakistan and Bangladesh exist as separate countries. The scars, considered together, are called the Radcliffe Line’.

Manan Kapoor is a writer with `Sahapedia`, an open online resource on the arts, cultures and heritage of India. This article is a part of `Saha Sutra`.