When India’s second coronavirus wave slammed the country last month, leaving many cities without enough doctors, nurses, hospital beds or lifesaving oxygen to cope, Sajeev V.B. got the help he needed.

Local health workers quarantined Sajeev, a 52-year-old mechanic, at home and connected him with a doctor over the phone.

When he grew sicker, they mustered an ambulance that took him to a public hospital with an available bed. Oxygen was plentiful. He left 12 days later and was not billed for his treatment.

“I have no clue how the system works,” Sajeev said. “All that I did was to inform my local health worker when I tested positive. They took over everything from that point.”

Sajeev’s experience had much to do with where he lives: a suburb of Kochi, Kerala.

Kerala officials have stepped in where India’s central government under Prime Minister Narendra Modi has failed, in many ways, to provide relief for victims of the world’s worst coronavirus outbreak.

Though supplies have tightened, Kerala’s hospitals enjoy access to oxygen, with officials having expanded production months ago. Coordination centres, called war rooms, direct patients and resources. Doctors there talk people at home through their illness. Kerala’s leaders work closely with on-the-ground health care workers to watch local cases and deliver medicine.

“Kerala stands out as an exceptional case study when it comes to proactive pandemic response,” said Dr Giridhar Babu, an epidemiologist at the Public Health Foundation of India, which is based in Gurgaon. He added, “Their approach is very humane.”

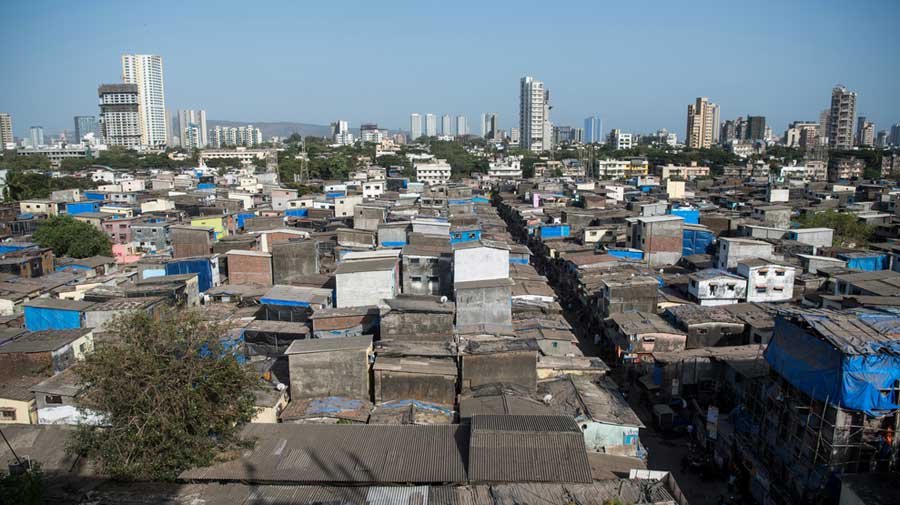

An ad hoc system of local officials, online networks, charities and volunteers has emerged in India to fill the gaps left by the stumbling response of the central government and many states. Patients around India have died for lack of oxygen in hospitals where beds filled up quickly.

Kerala is by no means out of trouble. Deaths are rising. Workers face long hours and tough conditions. The situation could still worsen as the outbreak spreads.

On paper, Kerala’s death rate, at less than 0.4 per cent, is one of India’s lowest. But even local officials acknowledge that the government’s data is lacking. Dr Arun N.M., a physician who monitors the numbers, estimates that Kerala is catching only one in five deaths.

A relatively prosperous state of 35 million, Kerala presents particular challenges. Over 6 per cent of its population works abroad, mostly in the Middle East. Extensive travel forces local officials to carefully track people’s whereabouts when a disease breaks out.

Kerala’s policies can be traced to the earliest days of the outbreak, when a student returning there from Wuhan, China, in January 2020 became India’s first recorded coronavirus case. Officials had learned lessons from successfully tackling a 2018 outbreak of the Nipah virus, a rare and dangerous disease.

As borders closed last year and migrant workers came home, the state’s disaster management team swung into action. Returning passengers were sent into home quarantine. If a person tested positive, local officials traced their contacts. Kerala’s testing rate has been consistently above India’s average, according to health data.

Experts say much of the credit for the system lies with K.K. Shailaja, a 64-year-old former schoolteacher who until this week was Kerala’s health minister. Her role in fighting the Nipah virus inspired a character in a 2019 movie.

“She led the fight from the front,” said Rijo M. John, a health economist from the Rajagiri College of Social Sciences in Kochi. “Testing, tracing and tracking of contacts were very rigorous from the beginning.”

Local officials like Shailaja have come under intense pressure.

Last year, Modi imposed one of the world’s toughest lockdowns on the entire country, a move that slowed the virus but drove India into recession. This year, Modi has resisted a nationwide lockdown, leaving local governments to take their own steps.

India’s states are also competing against each other for oxygen, medicine and vaccines.

“There has been a tendency to centralise decisions when things seemed under control and to deflect responsibility towards the states when things were not,” said Gilles Vernier, a professor of political science at Ashoka University.

To coordinate resources, Kerala officials assembled the war rooms, one for each of the state’s 14 districts. In the district of Ernakulam, where Sajeev V.B. lives, a team of 60 staffers monitors oxygen supplies, hospital beds and ambulances. Thirty doctors keep tabs on the district’s more than 52,000 Covid patients.

The war rooms collect data on hospital beds, ventilators and other factors, said Dr. Aneesh V.G., a medical officer in the district.

When doctors, via telephone, determine that a patient needs to be hospitalised, they notify the war room. Case numbers pop up on a giant screen. Workers decide what kind of care each person needs and then assign a hospital and an ambulance.

A separate group monitors oxygen supplies, calculating the burn rate of each hospital. Pointing to a screen, Eldho Sony, a war room coordinator, said, “we know who needs supply urgently and where it can be mobilised from.”

Dr Athul Joseph Manuel, one of the doctors who designed the war room, said triage had been crucial.

“In many cities across the world, lack of medical resources was not the primary issue,” he said. “It was the uneven distribution of cases that led to many hospitals getting overwhelmed.”

Other places have set up similar centres, with varying effectiveness.

Health experts say Kerala’s have worked because the state has a history of investing in education and health care. It has more than 250 hospital beds per 100,000 people, roughly five times India’s average, according to government and World Health Organization data. It also has more doctors per person than most states.

Officials have also worked closely with state health clinics and with local members of a national network of accredited social health activists, known in India as Asha’s.

The workers make sure that patients stick to their home quarantines and can get food and medicine. They also preach mask-wearing, social distancing and the virtues of vaccination. (Kerala’s share of fully vaccinated people is nearly double the national average of 3 per cent.)

The work is low-paying and difficult. Geetha A.N, a 47-year-old social health activist who is the first point of contact for 420 families, begins her rounds at 9am. She delivers medicine door to door and asks if any households need food. Her phone rings nonstop, she said, as patients call for advice or for help finding a bed.

Workers like her are intended to be volunteers, so Geetha’s pay is low and infrequent. She makes about $80 (Rs 5,800) a month but must buy her own protective gear.

“In the early days, we got masks, sanitizers and gloves,” she said. “Now, we have to buy them ourselves.”

A political shuffle has led some experts to wonder whether Kerala can keep its gains. Earlier this week, the CPM, which controls the state government, excluded Shailaja from its cabinet.

“Even the best-performing governments,” Professor Vernier of Ashoka University said, “are not immune from shooting themselves in the foot”.

New York Times News Service