Farhana Shaikh used to recoil in disgust when she went to the communal toilet in Dharavi. But since the pandemic struck, efforts to fight Covid-19 have dramatically improved public sanitation in one of Asia’s largest slums.

New cases have plunged in the Mumbai slum in recent weeks as officials bolstered anti-virus measures first put in place last year — from mass testing to disinfections in public areas, including bathrooms.

“The toilet is being cleaned every day since the last year as against once a week earlier. There’s soap and sanitiser and a box for disposing sanitary pads that were otherwise strewn around,” Shaikh, 30, said.

“People are also more cautious now: they are using masks and sanitisers... exposure to deaths and infections has made everyone fearful,” said the mother of one.

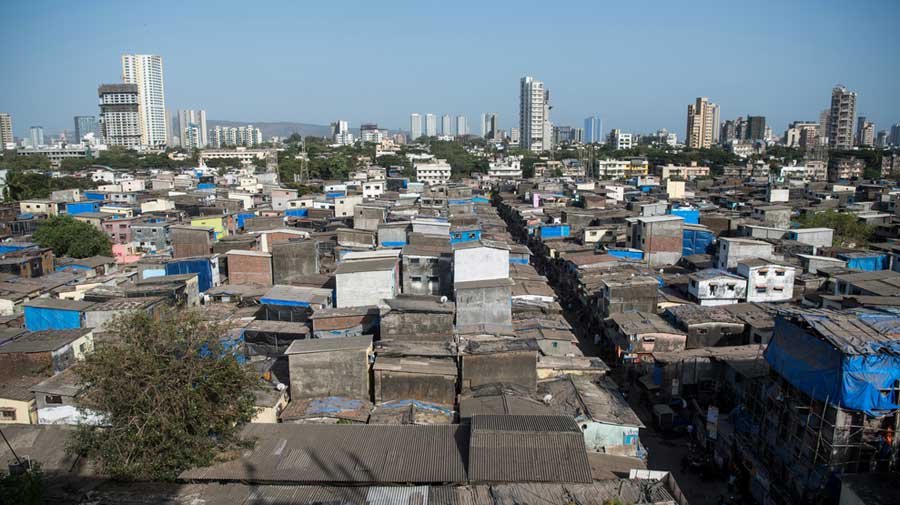

Home to 850,000 people cramped in 55,000 mostly one-room homes, Dharavi’s confirmed coronavirus cases fell to nine on Monday — down from a one-day peak of 99 a month ago, according to local government data.

Residents and local officials say that is largely the result of lessons learned during last year’s first wave of cases, when Dharavi defied expectations by tackling an initial surge in infections.

A testing protocol, including free tests for tens of thousands of residents, was revived as cases crept into double digits, fever camps were set up to scan for symptoms and quarantine facilities set up last year were reopened.

Despite vaccine shortages, announcements have blared out from loudspeakers across the slum, urging residents to get vaccinated. Another campaign sought to overcome vaccine hesitancy by offering free soap to anyone getting their jab.

“There is a strong community outreach, contact tracing continues and toilets are being deep cleaned with jet sprays,” said Yusuf Kabir, a water, sanitation and health specialist with Unicef, listing factors that helped the slum turn the tide.

“No one can guarantee it won’t be affected in the third wave. But Dharavi is not complacent,” he said.

‘We were going mad’

Wary of Dharavi’s potential to become a Covid-19 nightmare, Mumbai’s civic officials were closely monitoring cases in the neighbourhood when India’s deadly second wave took hold in March.

Initially, the slum’s quarantine centres were empty. “Everybody sensed if Dharavi was fine, Mumbai was fine. We slightly misjudged Dharavi’s quiet and calm as everything under control,” said Kiran Dighavkar, assistant municipal commissioner with Mumbai’s civic body.

Cases in Mumbai and Dharavi steadily increased through March, peaking in April to a daily high of 11,000 cases, before steadily coming down to less than 2,000 on Monday.

“The 15 days from April 10 to 25 were horrible... We were going mad,” Dighavkar said, adding that lessons learned in the slum had helped the city as a whole respond to the crisis.

“We adopted the Dharavi model of aggressive testing and screening. And that actually helped,” Dighavkar said.

Despite a cautious optimism that the worst is over, officials are already making plans for a possible third wave. Reuters