Wars are lost and wars are won, but it is probably in the nature of wars to never end. They get seeded in memory, uniquely rigged and purposed — as vanity, and often vainglory, of victory, as twisting humiliation of defeat, as tenuous truce waiting to come asunder and settle what was left unsettled, a singularly human stain that refuses to wash, or only bleeds to all washing. What war did not beget another? What war did not begin to resemble the debris of lessons not learnt from the previous one?

Among modern-world reporters of war, Leo Tolstoy blazed a trail. In the mid-19th century, he travelled to the Crimea with the battery of his soldier brother Nikolai and began to write about what he saw; he would later join the infantry and fight on a front that is still alive with combat between Russian expansionism and Ukrainian resistance. His Crimea time would become The Sebastopol Sketches, a classic of war reportage. Tolstoy also ran raids against “rebel mountain tribesmen” — the Chechens — in the north Caucasus. He conjured from that stint a haunting novella called Hadji Murat, an allegory of empire and defiance, and valour and betrayal. Its sounds and setting have often reminded me of Kashmir. A century-and-a-half on, the Russians were still busy cutting the Chechens down. They pounded Grozny, the capital, to pulp, then resurrected it and put a neon-and-granite polish on it. They still haven’t put out the Chechen fires. Hadji Murat, a Chechen protagonist crafted by a Russian writer at the turn of the 19th century, lives on.

Tolstoy’s later work became a searing invective against war; it was not about glory, it was “chaotic, disorienting and humbling”. His critique became one of the reasons he wasn’t awarded the Nobel Prize — his work had “denied the right of both individuals and nations to self-defence”. It’s probably what war also does, it insists on its necessity to the human condition.

This day 21 years ago, the guns fell silent over Kargil; artillery stopped popping on the peaks. It would take another fortnight for the frontlines to be secured, but July 12, 1999, was the day the fire ceased.

I was on my way back from Mushkoh. It lay, almost lost, in a cleft of hills, a valley redolent in its streams and the summer encampment of flowers. That’s how you’d imagine Mushkoh; that’s not how it was that summer. It had been cast under elaborate battle camouflage. Convoys had groaned over the flower beds and deposited their men and metalware. The dale was pimpled with tents and pitted with field-guns. Pack mules and battle-grimy soldiers washed in the streams. Many of their mates had returned from the fighting on hilltops prone on stretchers or doubled over on mulebacks, dying or dead. The air smelt of diesel and tincture; when the guns began to boom it turned pungent with saltpetre. War had accosted Mushkoh and lavishly sullied its Eden.

That last afternoon, I had heard two stories that have stayed. Two soldiers, both young, both in love, both dead.

Capt. Jerry Premraj had left his artillery position to join infantrymen scrambling up Point 4875, a craggy rogue of a massif that looms over Mushkoh. The peak had to be vacated of infiltrators, Premraj was meant to guide fire. He took it instead. A bullet smacked his arm and burst a critical vein. He persisted up the trail under fire and had his chest fatally riddled. He had been married barely two months to his childhood sweetheart.

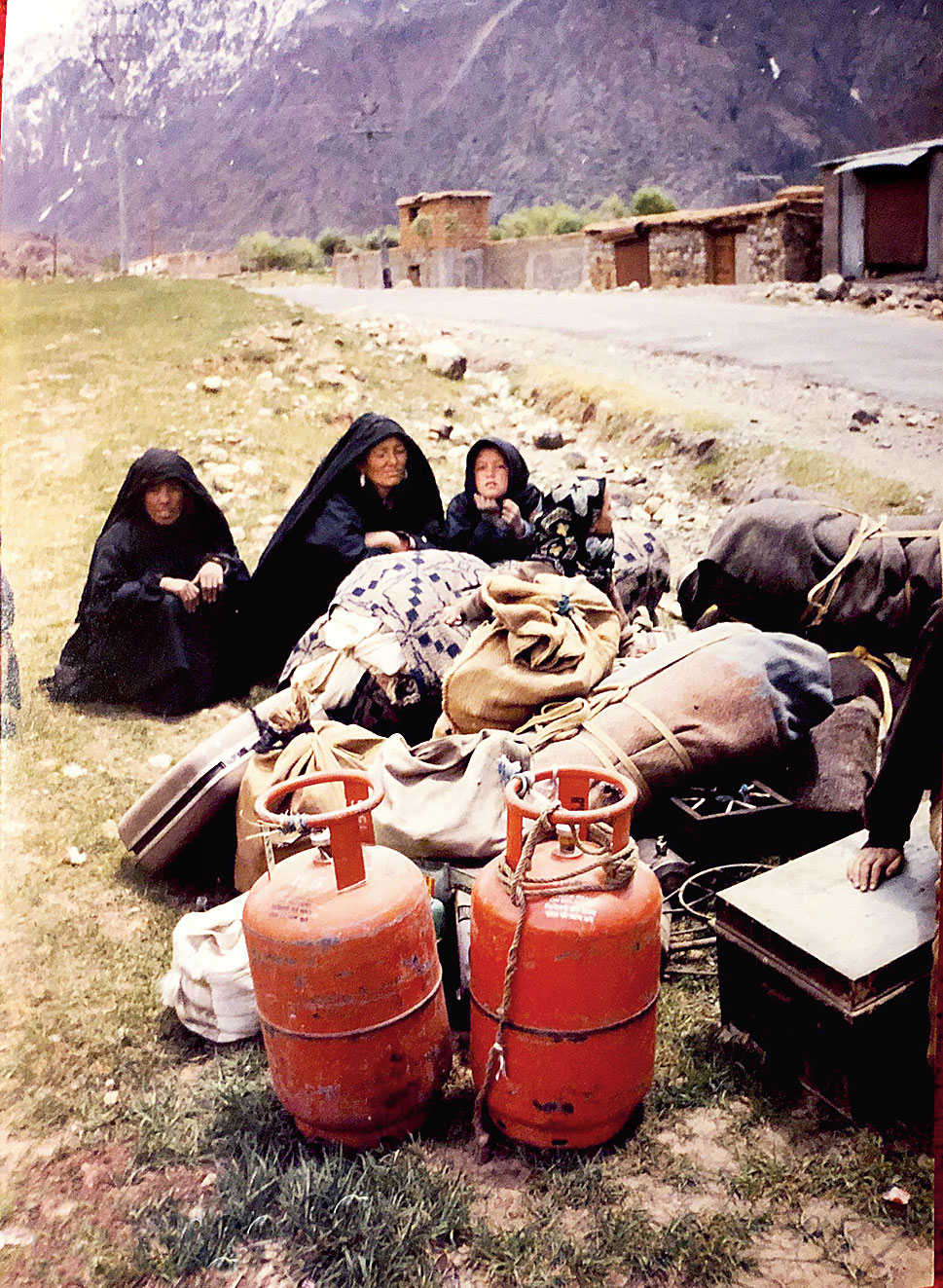

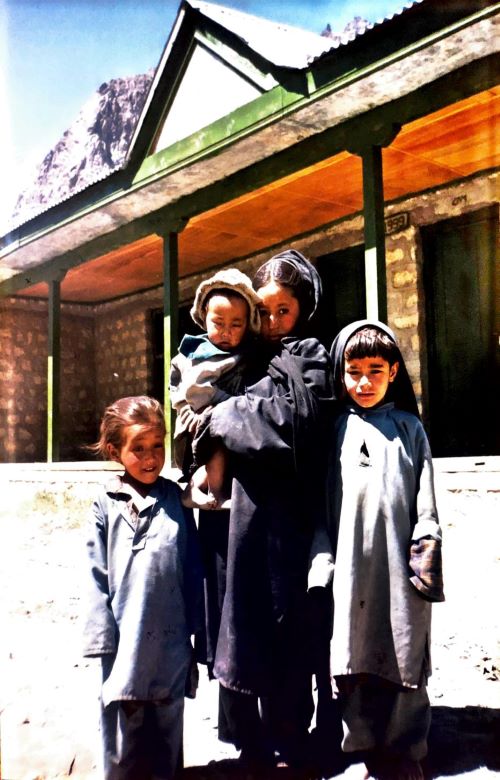

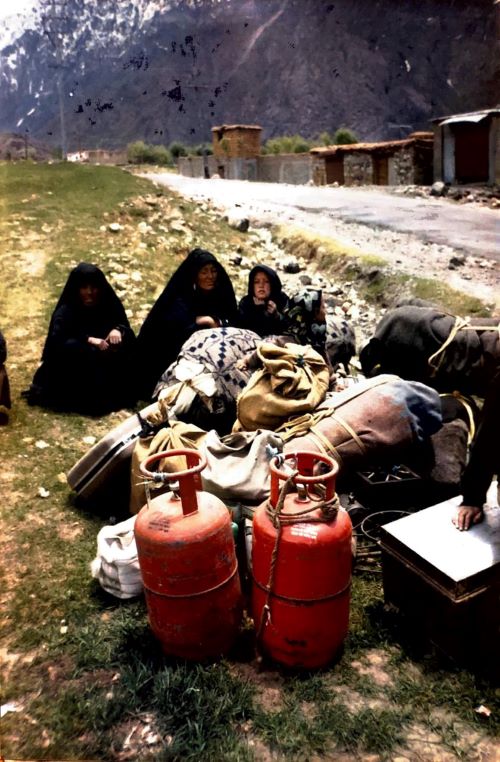

The photographs you see on this page do not look like images from a theatre of war. There’s no drama in them, no fervour. No gallantry, no heroics, neither uniform nor rank, nothing that would stir passion. Sankarshan Thakur

Capt. Imtiaz Malik of the Pakistani Army’s 165th Mortar Regiment perished trying to retain command of the top of Point 4875. What they got back to the Mushkoh camp, as trophy of battle, was his rent and riddled shirt. In the breast pocket of it was found a letter from his wife Samina postmarked June 14 from Islamabad. There were also two folded cards, missives of the kind young lovers send each other, that Capt. Malik had kept on his person through to the end.

Capt. Premraj and Capt. Malik were probably combatants for sway over Point 4875; it is unlikely we will ever know who fell first. That peak still stands.

It was tough getting out of Mushkoh. It had rained intermittently all day, a chill rain that fell slanted in high velocity winds, and by nightfall the sky had begun to thunder like it was mimicking the stereophonics of war. Turbulent causeways had erupted on the rutted road; we stayed in the rain and the darkness, the engine and the lights on the jeep shut, still as a startled beast of the jungle, until the waters calmed and it was possible to pass.

The photographs you see on this page do not look like images from a theatre of war. There’s no drama in them, no fervour. No gallantry, no heroics, neither uniform nor rank, nothing that would stir passion. They don’t sing of the anthem, they aren’t the stuff of goosebumps. But they all are images from a theatre of war.

The photograph on top is the range the battles of 1999 were fought over; Mushkoh would be to the extreme left, curtained off. The photographs of these children, women and men are photographs of those the exhaust of that war coughed out of their lives and habitations and rendered pitilessly adrift. I do not recall these individuals, nor exactly where they were shot in the way they were. They would have been from locations along the war-bitten National Highway 1A between Pandrass and Mingee, close to Kargil. They were random pickings on the way to more important destinations and stories, sundry material to be squirrelled away for use on relati-vely uneventful days on the front, back of the queue stuff, stories that could await their telling. It’s taken 21 years.

They don’t sing of the anthem, they aren’t the stuff of goosebumps. But they all are images from a theatre of war. Sankarshan Thakur

They didn’t have much to tell, that I do remember. They were bewildered folks, most of them, not able to articulate their bewilderment. “Paar se shelling…. Shelling from across” is how they understood and conveyed it, the complex gamut of militarised geopolitics distilled to a simplicity nobody could have a quarrel with. “Paar se shelling” — it contained both cause and consequence, and somewhere in between the seismic upturning of their lives. Hundreds of villages and hamlets had either been abandoned in dread or emptied to make way for the arrangements of war. Settlements had been bombed to rubble. I remember a dead horse, its neck ripped by flying shrapnel. I remember villagers complaining about their horses most of all — they had either fled in fright, or been maimed or killed. What does one do in those parts without a horse? I remember an elderly woman moaning that her husband had loaded gas cylinders onto their mule but left the stove behind. I remember an old man telling me he hadn’t eaten in days because he had no teeth and could only eat boiled oats. But there was nowhere to boil and no oats either. I remember a matriarch in a village called Silmoo feeding her voluptuous harvest of peaches to cows and to the sheer Sindh gorge because she was sick of the smell of ripened peaches and there was nowhere else to take them. I remember a young soldier from a little later the same day. He had had to be assisted back from embattled heights above Batalik because his body had begun to swell and he could walk no more. He hadn’t been injured, he hadn’t seen battle. The thought of it had struck such fright in him he could not urinate. He was a flagrant turmeric with sickness and morose as a boy who had proved himself unequal to the task. I remember a hotel hand called Ali who only walked barefoot because he had a prized pair of shoes and he would not have them ripped by mortar fire; his soles had turned thick and dark as hide. I remember little schoolgirls in scarves trying to repeat lessons after their teacher along a strip of land by the river in Mingee; the waters roared so loud, they looked like performers in a roadside pantomime. I remember the same girls scattering away like a flock of panicked birds at the report of distant bombing. I remember a woman, her leg freshly amputated, cheerfully caressing the gift of a new crutch. I remember a little girl in the Kargil bazaar with an eye and a gouged out space that resembled the shape of an eye. I remember a woman trying to heat a canister of brackish river water on a Bunsen burner so she could wash herself clean; she had just given birth on a ward bed in the Kargil hospital, and she was alone save her newborn announcing his arrival in wails. The piece of cloth she was dipping into the canister and wringing was blotched red. I remember being told by the man at the hospital gate, possibly a guard, that the doctors and all staff had been summoned to help that morning with a rush of injured soldiers: “Paar se shelling.”

This day last year, I was back in Kargil another time for another anniversary. Sadiq, the owner of Hotel Siachen, our wartime shelter, received me warmly and sat me down for a cup of tea, and after a while’s silence, said: “Don’t get me wrong, but must you come back and remind us?”

Close to my native place in north Bihar, at the centre of the district town of Darbhanga, there still exists a grubby waterbody locally known as Harahi. Harahi comes from the Sanskrit root “hadd” meaning bone, and by it hangs a Mahabharata tale. Harahi is so called because it is believed to contain the bones of the dead transported from the Kurukshetra battlefield. Harahi is forever tainted, to this day its water can be put to no good use. It’s what war also does; it doesn’t need reminding, it refuses to be forgotten.