Rubaiya delivered today. At 11 am, in a friend’s home at Gundmongolpore, a hamlet in Trespone, Rubaiya achieved what her family thought was impossible.

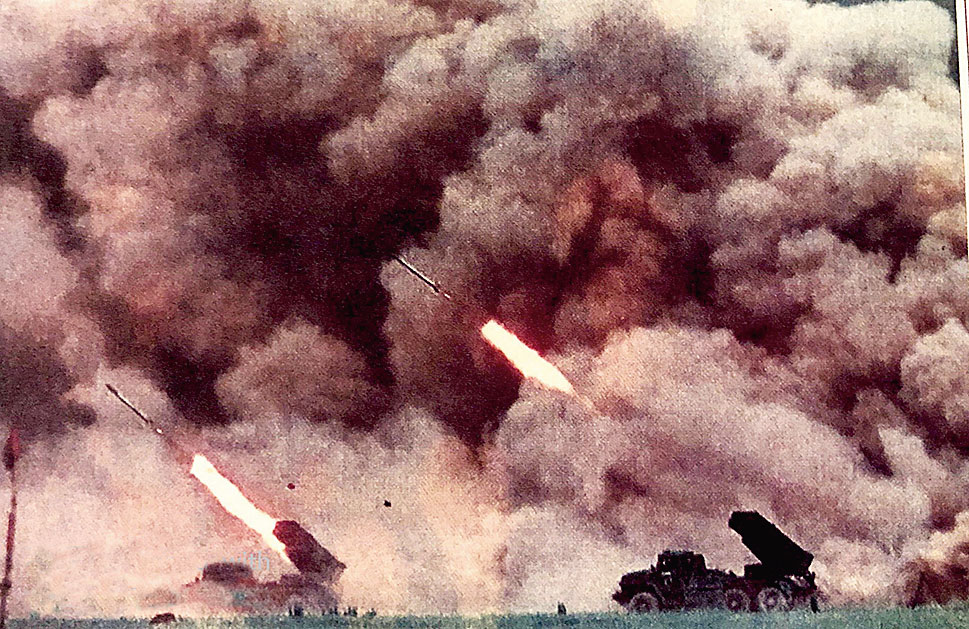

Three days ago, the woman in her early 20s left for her village Lamochan near Drass, where the army’s battery of Bofors howitzers is engaged in battle with Pakistani 210mm guns.

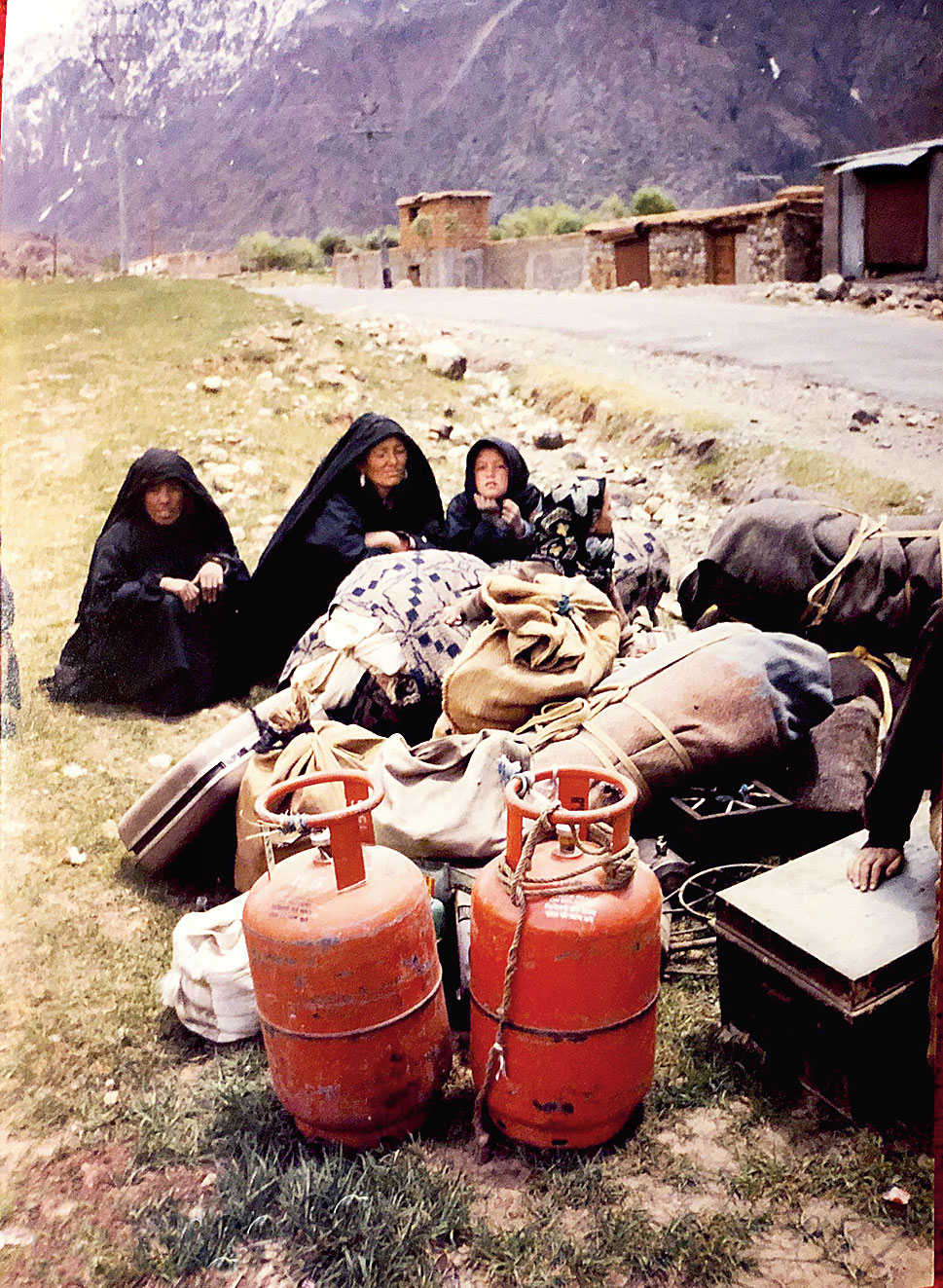

Her father, Abdul Karim, had left Lamochan with his brood of eight for Trespone on May 13. For two weeks, Lamochan had been battered by Pakistani artillery. “Not a sparrow could stay here,” says Karim of his 40-household village.

The villagers have shifted here and to Mingee, in the Valley of the gurgling Suru river where poplars form a green band that bisects eastern Ladakh’s mountainscape. “I sent my daughter, not any of my sons, back for some work because I assumed the army and police would not cause harm to a woman,” says Karim.

Lamochan is about 70km west of Kargil, a little off NH 1A to Srinagar. For nearly 65km, the road is exposed to Pakistani firing. There are also checkposts of the Jammu and Kashmir Police and the army whose ways the locals dislike because they know they are not trusted.

Rubaiya first got a lift on a lorry till Kargil. Then, she walked till another lorry driver, who was picking up villagers along the way and charging Rs 10 per head, dropped her at Drass. From Drass, she walked the 8km to her village. “It was so desolate I was scared,” she says. “I have stayed there all my life and it used to be so full of people, people I knew, people I grew up with. Many of them are here in Trespone, homeless and living on charity.”

Rubaiya’s father owned some land and livestock. “I lost two cows and three sheep to shrapnel,” says Karim. “I had told Ruby to be very careful not only because of the shelling but also because she is a woman and there are so many checkposts on the way.”

As luck would have it, Rubaiya found a family she was acquainted with near Drass. They run a tea-stall frequented by soldiers and truck drivers. She put up with them for two nights, slipping out by day to carry out the task she was assigned by her father.

At dawn today, she was told by the tea-stall owner’s wife that an elderly Sardar — a lorry driver — had dropped in. He was headed for Kargil. If Rubaiya thought it was worth the risk, she could ask for a lift.

Minutes later, she emerged from the hut looking very pregnant. At Kargil, where she was dropped two-and-a-half hours later, Rubaiya headed for the taxi stand. She asked after an acquaintance, a taxi driver whose native village is Lamochan but who has been living in Kargil for the last two years. He was not to be found.

Steeling herself, Rubaiya walked. At Baru, Kargil’s administrative hub, she was asked by the police where she was going. She said her destination was the emergency wing of the Kargil District Hospital that had been shifted from the shelling zone where it was originally situated.

Two hours later, in Trespone, a breathless Rubaiya delivered: three kilos of rice, cash and jewellery — her family’s savings.

This story was first published in The Telegraph in 1999