The official Covid-19 figures in India grossly understate the true scale of the pandemic in the country. Last week, India recorded the largest daily death toll for any country during the pandemic — a figure most likely still an undercount.

Even getting a clear picture of the total number of infections in India is hard because of poor record-keeping and a lack of widespread testing. Estimating the true number of deaths requires a second layer of extrapolation, depending on the share of those infected who end up dying.

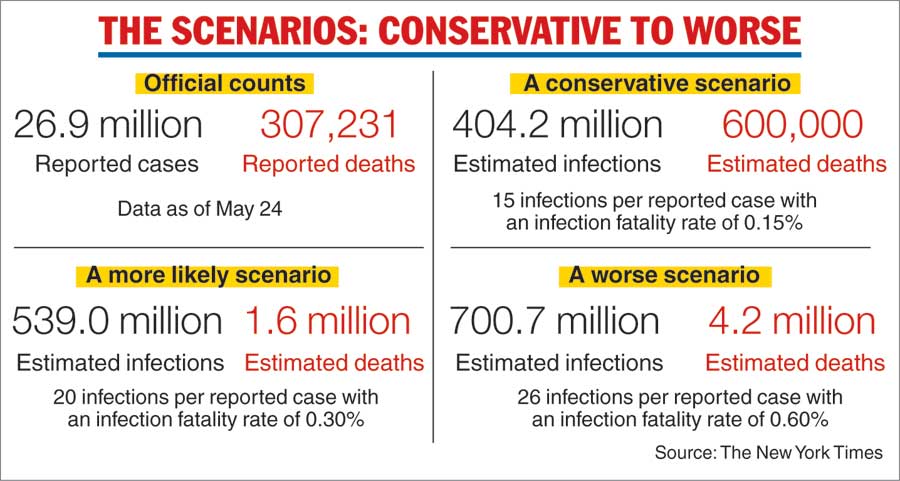

In consultation with more than a dozen experts, The New York Times has analysed case and death counts over time in India, along with the results of large-scale antibody tests, to arrive at several possible estimates of the true scale of devastation in the country.

Even in the least dire of these, the estimated infections and deaths far exceed official figures. The more pessimistic ones show a toll on the order of millions of deaths — the most catastrophic loss anywhere in the world.

India’s official Covid statistics report 26,948,800 cases and 307,231 deaths as of May 24.

Even in countries with robust surveillance during this pandemic, the number of infections is probably much higher than the number of confirmed cases because many people have contracted the virus but have not been tested for it. On Friday, a report by the World Health Organisation estimated that the global death toll of Covid-19 may be two or three times higher than reported.

The undercount of cases and deaths in India is most likely even more pronounced, for technical, cultural and logistical reasons. Because hospitals are overwhelmed, many Covid deaths occur at home, especially in rural areas, and are omitted from the official count, said Kayoko Shioda, an epidemiologist at Emory University. Laboratories that could confirm the cause of death are equally swamped, she said.

Additionally, other researchers have found, there are few Covid tests available; often families are unwilling to say that their loved ones have died of Covid; and the system for keeping vital records in India is shaky at best. Even before Covid-19, about four in five deaths in India were not medically investigated.

To arrive at more plausible estimates of Covid infections and deaths in India, we used data from three nationwide antibody tests, called serosurveys.

In each serosurvey, a subset of the population (about 30,000 of India’s 1.4 billion people) is examined for Covid-19 antibodies. Once researchers have figured out the share of those people whose blood is found to contain antibodies, they extrapolate that data point, called the seroprevalence, to arrive at an estimate for the whole population.

The antibody tests offer one way to correct official records and arrive at better estimates of total infections and deaths. The reason is simple: Nearly everyone who contracts Covid-19 develops antibodies to fight it, leaving traces of the infection that the surveys can pick up.

Even a wide-scale serosurvey has its limitations, said Dan Weinberger, an associate professor of epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health. India’s population is so large and diverse that it’s unlikely any serosurvey could capture the full range.

Still, Weinberger said, the surveys provide a fresh way to calculate more realistic death figures. “It gives us a starting point,” he said. “I think that an exercise like this can put some bounds on the estimates.”

Even in the most conservative estimates of the pandemic’s true toll, the number of infections is several times higher than official reports suggest. Our first, best-case scenario assumes a true infection count 15 times higher than the official number of recorded cases. It also assumes an infection fatality rate, or IFR — the share of all those infected who have died — of 0.15 per cent. Both numbers are on the low end of the estimates we collected from experts.

The result is a death toll roughly double what’s been reported to date.

The latest national seroprevalence study in India ended in January, before the current wave, and estimated roughly 26 infections per reported case. Our second scenario uses a slightly lower figure, 20, in addition to a higher infection fatality rate of 0.3 per cent — in line with what has been estimated in the US at the end of 2020. In this scenario, the estimated number of deaths in India is more than five times the official count.

“As with most countries, total infections and deaths are undercounted in India,” said Ramanan Laxminarayan, director of the Centre for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy.

“The best way to arrive at the most likely scenario would be based on triangulation of data from different sources, which would indicate roughly 500 to 600 million infections.”

The third scenario estimates roughly 26 true infections per known case to account for the current wave. The infection fatality rate is also higher — double the rate of the previous scenario, at 0.6 per cent — to take into account the tremendous stress that India’s health system has been under during the current wave.

Because hospital beds, oxygen and other medical necessities have been scarce in recent weeks, a greater share of those who contract the virus may be dying, driving the infection fatality rate higher.

Because there are two different unknowns, there is a wide range of plausible values for the true infection and death counts in India, Shioda said.

“Public health research usually provides a wide uncertainty range,” she said. “And providing that kind of uncertainty to readers is one of the most important things researchers do.”

Case multipliers

So far, India has conducted three national serosurveys during the Covid-19 pandemic. All three have found that the true number of infections drastically exceeded the number of confirmed cases at the time in question.

The results of the three national serosurveys:

- The first survey, conducted between May 11 and June 4, 2020, estimated 6,460,000 infections, which was 28.5 times the 226,713 confirmed cases at that point.

- The second survey, conducted between August 18 and September 20, 2020, estimated 74,300,000 infections, which was 13.5 times the 5,490,000 confirmed cases at that point.

- The third survey, conducted between December 18, 2020, and January 6, 2021, estimated 271,000,000 infections, which was 26.1 times the 10,400,000 confirmed cases at that point.

At the time the results of each survey were released, they indicated an infection prevalence between 13.5 and 28.5 times higher than India’s reported case counts at those points in the pandemic. The severity of underreporting may have increased or decreased since the last serosurvey was completed, but if it has held steady, that would suggest that almost half of India’s population may have had the virus.

(If the official May 24 figure of infections, 26.9 million, is multiplied by 26.1 — the factor by which the latest serosurvey’s estimation of cases exceeded the official count at the time — one gets 702.09 million or about half of India’s population.)

Shioda said that even the large multipliers found in the serosurveys may rely on undercounts of the true number of infections. The reason, she said, is that the concentration of antibodies drops in the months after an infection, making them harder to detect. The number would probably be higher if the surveys were able to detect everyone who has been infected, she said.

“Those people who were infected a while ago may not have been captured by this number,” Shioda said. “So this is probably an underestimate of the true proportion of the population that has been infected.”

Like nearly all the researchers contacted for this article, however, Shioda said the estimator provided a good way to get a sense of the wide range of possible death tolls in India.

Death rates

Many of the infection fatality rate estimates that have been published were calculated before the most recent wave in India, so it could be that the overall IFR is actually higher after accounting for the most recent wave. The rate also varies greatly by age: Typically, the measure rises for older populations. India’s population skews young — its median age is around 29 — which could mean the IFR is lower there than in countries with larger older populations.

There is also extreme variability within the country in terms of both infection fatality rate and seroprevalence. In addition to the three national serosurveys, there have been more than 60 serosurveys done at the local and regional levels, according to SeroTracker, a website that compiles serosurvey data from around the world.

In a paper examining infection rates using serosurvey data from three locations in India, Paul Novosad, an associate professor of economics at Dartmouth College, found huge variability depending on the population being sampled.

“We found that the age-specific IFR among returning lockdown migrants was much higher than in richer countries,” he said. “In contrast, we found a much lower first-wave IFR than richer countries in the southern states of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.”

In a country as large as India, even a small fluctuation in infection fatality rates could mean a difference of hundreds of thousands of deaths, as seen in the estimates above.

While estimates can vary over time and from region to region, one thing is clear beyond all doubt: the pandemic in India is much larger than the official figures suggest.

New York Times News Servive

Sources: Dr Ingvild Almås, Stockholm University; Dr Murad Banaji, Middlesex University of London; Dr Tessa Bold, Stockholm University; Dr Selene Ghisolfi, Laboratory for Effective Anti-poverty Policies, Bocconi University; Dr Ramanan Laxminarayan, Centre for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy; Dr Bhramar Mukherjee, University of Michigan; Dr Paul Novosad, Dartmouth College; Dr Megan O’Driscoll, Cambridge University; Dr Jeffrey Shaman, Columbia University; Dr Kayoko Shioda, Emory University; Rukmini Shrinivasan; Dr Dan Weinberger, Yale School of Public Health. Data on serosurveys conducted in India comes from SeroTracker.