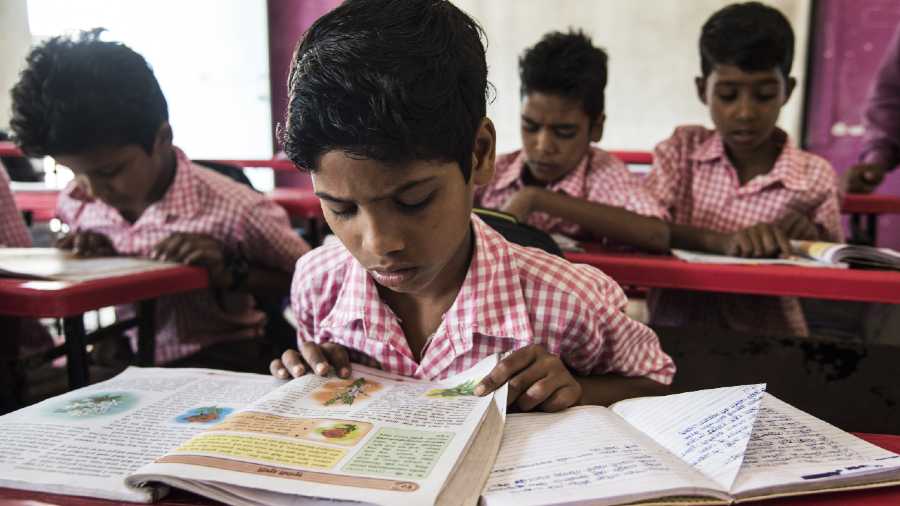

When Indian children began the school year this week, students in thousands of classrooms were issued new textbooks on history and politics that either watered down or purged key details from India’s past that Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ruling party finds inconvenient to its Hindu nationalist vision for the country.

The changes took aim at references to the links between Hindu extremism and the assassination of Mohandas K. Gandhi; the secular foundation of post-colonial India; and the 2002 riots in Gujarat, where hundreds of Muslims were killed in days of indiscriminate retaliatory violence at a time when Modi was the state’s top leader. Chapters on Mughal history, covering hundreds of years of Muslim rule, were either slashed or removed.

Among the deleted passages from 12th-grade history and politics texts:

- Gandhi’s “steadfast pursuit of Hindu-Muslim unity provoked Hindu extremists so much that they made several attempts to assassinate” him.

- Gandhi “was particularly disliked by those who wanted India to become a country for the Hindus, just as Pakistan was for Muslims.”

- “Instances, like in Gujarat, alert us to the dangers involved in using religious sentiments for political purposes. This poses a threat to democratic politics.”

The alterations, which had been under discussion since last year before being formalized in the newly printed curriculum, follow other efforts by Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP, to erase prominent Muslim marks on India’s history and politics, including the frequent changing of street and city names from Muslim to Hindu.

The governing party’s leaders have also tried to minimize the founding fathers’ arguments for why India’s diversity could survive only under a secular umbrella, co-opting the legacy of many secular leaders as they push to remake India into a Hindu-first nation.

With that divisive campaign, anti-Muslim hate speech has proliferated, holy sites have been aggressively contested and Hindu lynch mobs have killed Muslims on suspicion of slaughtering or even just transporting cows, which are considered holy by Hindus.

Political interference with education is not new to Indian democracy. Successive federal and state governments have tried to leverage education to their advantage, whether to further an ideological agenda, like stopping a sex education program in a BJP-ruled state, or for self-promotion, including a glowing portrayal of a political opponent of Modi’s party in a textbook section on a farmers’ movement.

Dinesh Prasad Saklani, director of the National Council of Educational Research and Training, an autonomous organization under the Ministry of Education that oversees textbook content, said the changes had been made to reduce the load on children after the pandemic. Chapters were removed to avoid repetition, and important information was condensed, Saklani said, “which will in no way affect a child’s knowledge.”

Even the removal of single words, he said, like one that identified Nathuram Godse, Gandhi’s assassin, as an upper-caste Hindu, was undertaken solely as part of that exercise.

“You tell me, when content load is being reduced during times of such trauma, if the experts felt such-and-such thing should be removed, so it was. How is it such a big thing? I mean, are all Brahmins assassins?” Saklani said, referring to Godse. Brahmins sit atop the caste hierarchy and are a large voting bloc for Modi’s party.

Saklani said that the education organization had nothing to do with either the BJP or the RSS, a powerful right-wing group that is the ideological fountainhead of Modi’s political party. (A reference to a ban on the RSS after Gandhi’s assassination was among the deletions.)

Members of RSS affiliate groups celebrated the changes on social media.

“In the minds of young kids, students, effort was made to stamp the sign of slavery and not the proud traditions of India,” Vinod Kumar Bansal, spokesman of one group, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, told an Indian news channel.

Opposition political parties, he said, had “taught us all by glorifying the history of the slavish Mughal period. Better late than never. This is an effort to remove all those chapters.”

The curriculum prescribed by the National Council of Educational Research and Training is used by the government’s Central Board of Secondary Education, which has over 20,000 affiliated schools, both public and private, across India. Its textbooks are also widely used as study material for exams for highly coveted jobs in the Indian bureaucracy.

Critics argued that the textbook changes could give students a warped impression of India’s history as Modi has linked himself to Gandhi’s legacy even as other leaders of the ruling establishment have rejected Gandhi’s principles, and as Godse has come to be revered by some groups, with one BJP member of Parliament even calling him a patriot.

“Gandhi’s assassination is a founding moment of our history, and we are still suffering,” said Prabhu Mohapatra, a professor of modern Indian history at Delhi University. “How would we know the exact details and context of why Gandhi was killed if not first in school?”

By plucking out material from the textbooks, he said, “the historical narrative has changed.”

The change in curriculum was a matter of extensive debate in the Indian news media as the newly printed books became officially available this week. One newspaper, The Indian Express, which reported extensively on the soft rollout of the changes last year, was scathing in an editorial on Thursday.

“The recent revisions invite the charge that not only does the government wish to escape unpalatable facts, but it also wants to ensure that students do not engage with social and political realities with a critical attitude,” the newspaper said.

The New York Times News Service