Even if we didn’t know that her official motto since 1956 is “In God We Trust”, those readers who have visited the US would be familiar with this phrase since it appears on many American currency notes and coins.

William Edwards Deming, a statistician and electrical engineer from the US, visited the Indian Statistical Institute, Calcutta, in 1946-47, 1951 and 1971, on invitation from Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, the doyen of statistical science in India.

Deming was one of the architects of the post-war economic miracle of Japan. Between 1950 and 1960, Japan became one of the leading economies of the world after suffering from near-complete devastation.

Deming emphasised the pivotal role of data and statistics in enhancing quality and productivity in industry and ensured the implementation of statistical quality control. He also helped initiate these systems in the Indian industry.

For his seminal contributions, Deming was awarded the National Medal of Technology by President Ronald Reagan in 1987 and, in the following year, the Distinguished Career in Science award by the US National Academy of Sciences.

Deming is also known for his famous statement “In God we trust, all others must bring data”. He emphasised the importance of data in development.

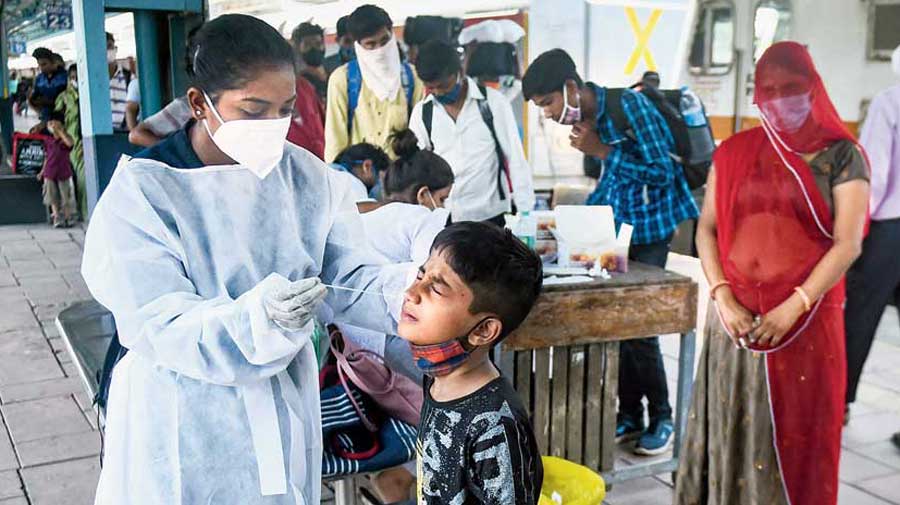

This pandemic has exposed the critical importance of data. However, data is not knowledge. Data have to be transformed into knowledge to provide a basis for action. In pandemic times, data have to be analysed rapidly for actionable inferences. This requires data to be shared openly in real-time, to enable many scientists to analyse and provide to policy makers the knowledge thus gained.

Data are collected through public funds. Therefore, citizens have a right to data access. To deny them this right is to deny them health security during the pandemic. In many countries, data pertaining to the spread of SARS-CoV-2, nature of clinical outcomes of infection by the coronavirus, reinfection after vaccination, new variants arising and their local spread are publicly available.

The knowledge gained from analyses of these data has influenced policy on implementation of restrictions such as lockdowns, estimation of logistical requirements such as oxygen cylinders, hospital beds and ventilators in local areas, and have also impacted public health systems. Open rapid data-sharing enhances transparency to citizens on reasons for decisions taken by the government.

RNA sequence data of a large number of coronavirus specimens are being generated everyday and made publicly available very rapidly in many countries. The volume of sequence data being generated in India is very small.

Further, viral sequence data that have been collected from India are being sparingly shared in the public domain. The time lag between data collection and data sharing is about an order of magnitude higher than that of many other countries, thereby rendering such data of little immediate public health utility in India.

If a dangerous variant of the coronavirus arises somewhere in our country, it will have spread rather widely before we can identify it based on sequence data.

Data must be at the core of any public health system. All public health decisions must be evidence-based. Data collection must be done systematically with a statistical design so that the collected data can inform a national public health system without bias.

Possibly, none of us has ever encountered a pandemic. And, each of us is hoping that we don’t encounter another. To make this hope come true, a high level of preparedness is essential. Preparedness to identify a local outbreak without delay. Preparedness to monitor and contain spread. Preparedness to care for the infected. Preparedness to identify new variants. And much more.

We need to establish an unbiased, systematic and wide method of data collection. We need to build a robust system for rapid data-sharing, analysis and dissemination of results. Only then can our preparedness be sound.

As Deming had said, we must bring data to the table to enable preparedness. In a country such as ours, systematic and wide data collection is of even greater importance because we are a group of people with varied ancestries that has resulted in a heterogeneous gene pool.

This genomic diversity among the people of India implies that we may not be equally susceptible to an infection, we may not display the same set of symptoms if we are infected, we may not respond equally to a vaccine. This imposes a heavy burden of data collection on us, because we need to be inclusive of the various ethnic groups in our country. One size does not fit all!.

Frustrated that data collection was not being systematically done during the pandemic and the inability to obtain access to data collected, on April 29, 2021, a group of about 200 scientists wrote an open appeal to the Prime Minister “for systematic data collection and timely data release”.

The number of signatories to the appeal snowballed to over 900 within a couple of days, indicating how widespread the concern of scientists in India is.

The appeal evoked a supportive response from the principal scientific adviser to the Prime Minister. He stated: “Wide and correct access to data and information and wide collaboration are important at any time and most urgent now.”

He also promised to take “proactive measures” and provided details of contact persons for “specific questions, concerns, and suggestions about data access”.

I, and many others, had immediately contacted them to gain access to specific data. As we were then told, we also submitted “concept notes” explaining why we needed access to the data and how we planned to utilise these. That was over a month ago. We are still waiting for data access.

Unfortunately, in our country, time is never the essence. Data-hungry scientists wished to find patterns in the data in a bid to help the government curb the disastrous course of the disease. But alas! It’s time for the scientists to go to bed hungry, with frustration that they were unable to use their expertise for societal benefit.

The author is a National Science Chair, Government of India, and an Emeritus Professor of Indian Statistical Institute